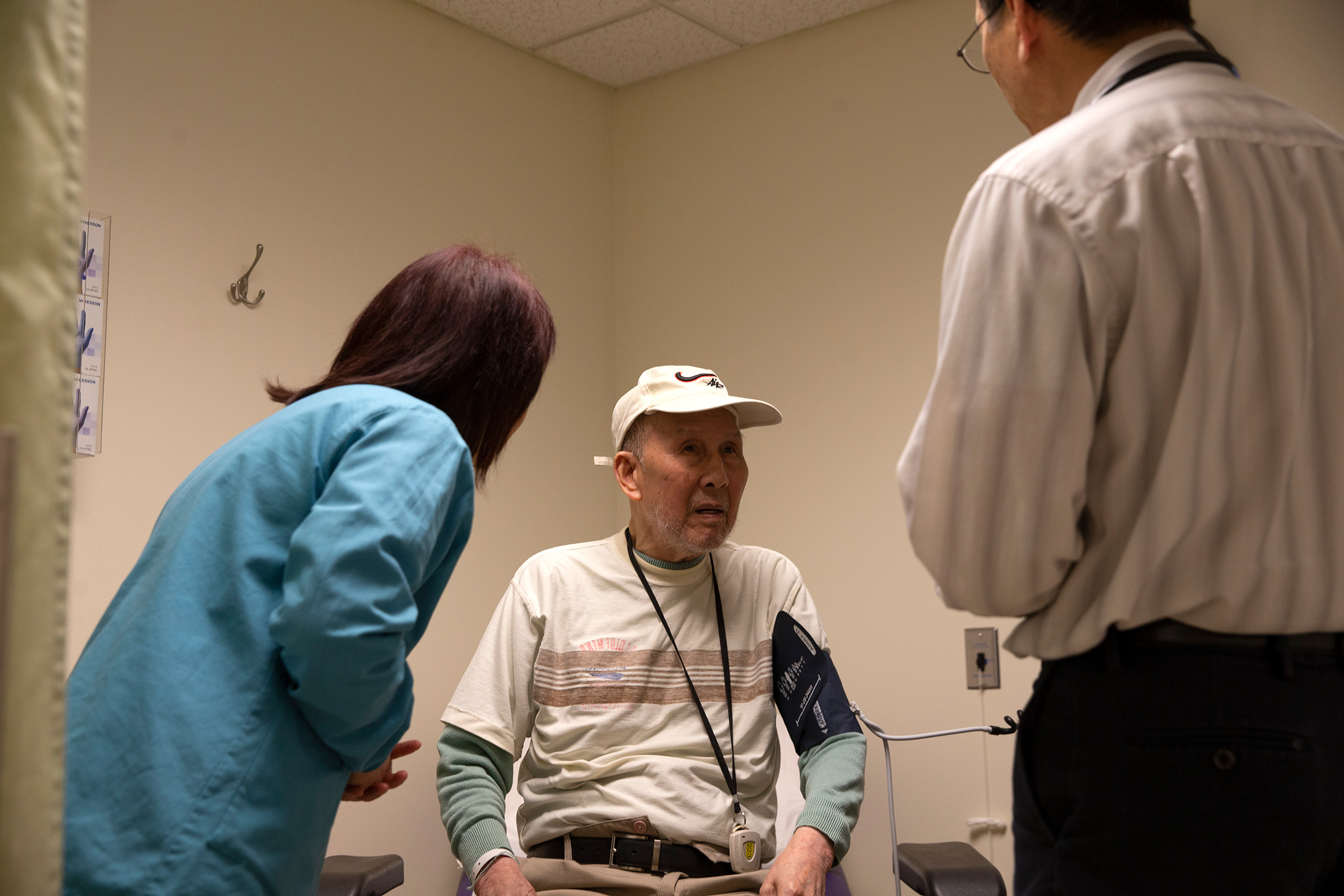

At the University of Louisville hospital in Kentucky, dozens of patients each day need the help of an interpreter to understand their medical conditions and make informed choices about their care. Before patients in the area showed COVID-19 symptoms, medical interpreters provided translations for as many as 30-40 people each day in Spanish or Amharic—a language spoken primarily in Ethiopia.

Like the estimated 100,000 interpreters who work at hospitals across the country, their services — translating word-for-word between doctor and patient, maintaining patient confidentiality and accounting for cultural nuances — can mean the difference between life or death. “Any good doctor is only as good as how they are understood by the patient,” says Natalya Mytareva, executive director of the Certification Commission for Health Care Interpreters (CCHI), one of the national certifying bodies for medical interpreters. “If the doctor is basing the diagnosis on the wrong information because they didn’t have an interpreter, then what good is that doctor?”

Keep up to date with our daily coronavirus newsletter by clicking here.

As Jefferson County, which includes Louisville, becomes one of the hardest hit counties in the state (42 people have died there of COVID-19 as of Monday morning, the most of any Kentucky county so far, according to data by Johns Hopkins University), the number of patients in need of care at the hospital is even higher. But the hospital’s nine medical interpreters are mostly gone. On March 21, the hospital gave them two options: continue to work face-to-face as an interpreter or take vacation time and unpaid leave.

“At this time [University of Louisville] will NOT be offering any work from home options for language services,” an email, obtained by TIME, said. “It will also NOT be an option to interpret over the phone.” (In an emailed statement to TIME, University of Louisville Hospital spokesperson David McArthur said all members of the interpreting staff still providing face-to-face services are provided with personal protective equipment.)

It’s a dilemma gripping hospitals across the country that, in order to receive federal assistance, must make their services available to the 65 million Americans who speak limited English. But as health care systems become overwhelmed with cases of COVID-19 and states implement stay at home orders, more than a dozen medical interpretation professionals who spoke to TIME from New York City, Boston, San Francisco, Minnesota, Kentucky, Wisconsin, Ohio and Idaho say their industry is being upended during the pandemic. Unemployment is increasing while hospitals attempt to quickly adapt to remote interpreting services. And they say that could have a negative impact on patient care, particularly as the pandemic has disproportionately affected minority communities that require interpretation in many cities across the country.

“This really comes down to it being a public health concern and a safety concern,” says Dr. Lucy Schulson, a primary care physician and research fellow at Boston Medical Center who studies health disparities, particularly in immigrant populations and people who speak limited English. “Study after study has demonstrated that access to professional interpreters is critical for the care of patients with limited English proficiency.”

As a solution, many hospitals like the University of Louisville have turned to third-party companies that offer remote interpreting services such as LanguageLine Solutions. Another remote service, Certified Languages International, has seen a 70% increase in interpreters inquiring how to work for the company. Other hospitals have set up call centers, where interpreters can keep a distance from each other and still provide interpreting services through phone call or video. Hospitals are required by law to maintain the privacy of their patient’s medical history, so hopping on a call with a medical interpreter using FaceTime or Zoom, platforms that do not offer proper end-to-end encryption, isn’t an option.

Face-to-face interpretation with a certified professional is ideal, says Mytareva. However, amid the COVID-19 outbreak, more and more hospitals are attempting to establish remote services, but not all have the infrastructure to transition quickly, she says.

Salome Mwangi, 50, who is from Kenya and moved to Boise, Idaho, through a refugee resettlement program, is a medical interpreter for patients who speak Kiswahili. About three weeks ago, Mwangi was told to cancel all her appointments. The clinics and doctors’ offices she interpreted for would instead utilize a third-party vendor to provide phone and video interpreting.

Mwangi says that the in person part of interpretation is important because of dialectal nuances and how much of communication is non verbal. “If I’m talking to you over the phone, there may be body language you’re exhibiting that I might not be able to read,” she tells time.

“Patients may not say, ‘I have no idea what you just said,'” she says. It’s the patient’s body language that gives Mwangi the cue that a patient may not understand what she’s saying. She worries an interpreter in another part of the country who can’t see the patient in person might not be able to understand those cues.

“What we have seen is a shift in the need to have [interpretation] fast and at a higher level of safety for the people involved,” says Enrica Ardemangi, president of the board of the National Council on Interpreting Health Care and a medical interpreter for Spanish.

That need for fast interpretation is better met at some hospitals that already had been utilizing some type of telephonic or video interpreting service, Ardemangi says. In those locations, the time it takes to connect to a remote interpreter might not be as great a factor playing into the quality of care limited English speaking people receive. But if a hospital had been primarily utilizing face-to-face interpreters and had to suddenly switch to remote interpreters, “it could create delays in having interpreting services available.”

For that reason, one interpreter at the University of Louisville Hospital—who asked TIME to conceal her first and last name because she feared professional repercussions for speaking candidly and could be easily identified given the small size of her team—worries about COVID-19 patients there.

As cases continue to grow, she worries about hospitals across the country competing for interpreters who may already be occupied on third-party digital platforms, especially when it comes to rarer languages. “And when those wait times become prohibitive, providers won’t wait for them,” she says.

“What I think the pandemic highlights is the actual preparedness to serve patients who don’t speak English,” Mytareva adds. “If a hospital didn’t have [language access] set up pre-pandemic, now it would definitely be at a loss, grasping for how to coordinate.” While hospitals attempt to establish those remote connections amid a pandemic, limited English speaking patient’s health outcomes are jeopardized. Under unprecedented circumstances in overcrowded facilities, tough decisions about health care have to be made.

But, Mytareva says, the coronavirus pandemic can make hospital systems aware that it probably never provided proper language access to begin with. “They never were equipped,” she says. “And of course, now everyone is scrambling.”

Dr. Ramon Tallaj has seen first-hand the way COVID-19 has impacted immigrant populations and people who speak limited English. On the evening of April 4, Dr. Tallaj and his partners at SOMOS—a nonprofit that created a network of health care providers who work to improve access for New York City’s immigrant populations—worked to recover the body of an undocumented man whose primary language was Spanish. The man shared on Facebook before he died that he had heard he could be fined for attempting to get tested for the virus as an undocumented person, according to SOMOS co-founder Henry Muñoz, and so he didn’t seek medical care.

“Our limited English proficient communities deserve the same level of care as everybody else,” says Shiva Bidar-Sielaff, chief diversity officer at University of Wisconsin Health, who oversee’s the hospital system’s language access programs. “Take a moment and think about how it must feel to be a limited English proficient person with no visitors and no other ability to communicate.”

That scenario is one the interpreter in Louisville is very concerned about. “If our system continues this course of action,” she says, “it’s very possible that all those people will be alone and unable to communicate in their last moments of life. It’s terrifying.”

Please send any tips, leads, and stories to virus@time.com.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jasmine Aguilera at jasmine.aguilera@time.com