On Oct. 8, 1918, faced with the reality of that year’s flu pandemic, the chancellor of the University of Kansas ordered a temporary shutdown of the school, expecting it to only last for a week. The front page of the University Daily Kansan announced the decision. “BY AUTHORITY AND DIRECTION OF THE STATE BOARD OF HEALTH there will be NO CLASSES in the University beginning at NOON today, October 8,” read the proclamation. “The University will re-open Tuesday, October 15, unless notice is given to the contrary. Students are FORBIDDEN to leave Lawrence—to do so would help spread infection. They must remain in Lawrence.”

By the time the closure actually ended a month later, almost 1,000 members of the university community, including students and faculty, had fallen ill with the flu.

For some students, though, life went on as normal—or, rather, as normal as could be at the height of a global public-health emergency. The so-called “Spanish flu” spread in three main waves, starting in March 1918 and coming to an end by the summer of 1919. The pandemic’s peak was during the second wave, which began in September 1918 and lasted through the fall. Spread in part by the war, the virus killed almost 200,000 Americans in October 1918 alone.

It was after witnessing the worst of the virus that one student at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, wrote a letter to her aunt. More than a century later, as the world confronts another pandemic, the letter provides a look at what life was like at that moment—and how even the deadliest pandemic of modern history was the new normal for those who lived through it.

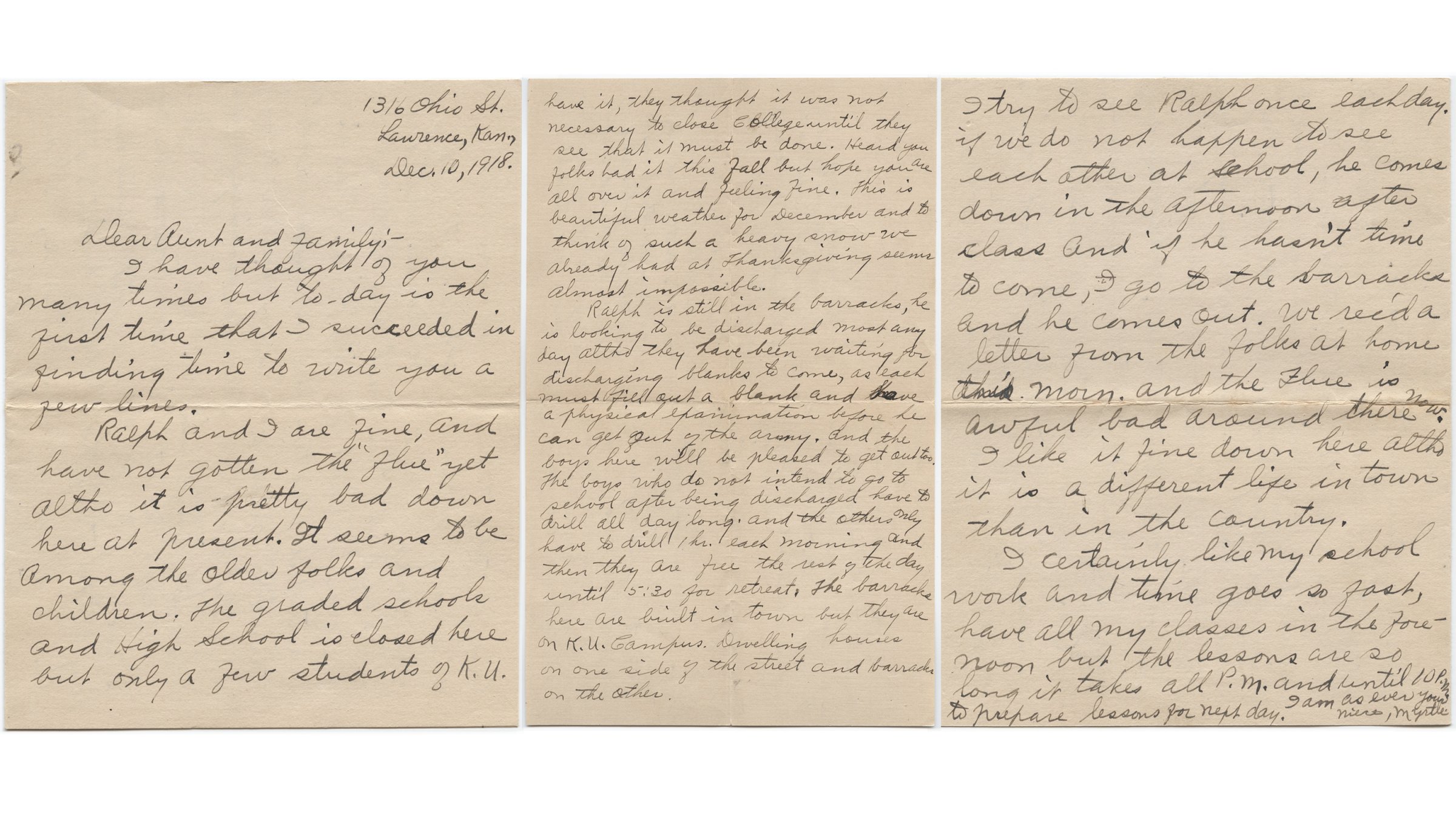

In the letter, the student, Myrtle, mentions that the flu—which she spells “flue,” a not-uncommon spelling at the time—“is awful bad” where her parents are and that schools near her university have shut down because it’s “pretty bad” there too. The note, pictured above and transcribed below, is part of a larger collection of letters donated by the descendants of Jacob Myer to the National World War I Museum and Memorial; Myer, whose mother was the recipient of the letter, eventually died of the flu.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Myrtle’s experience is one with which many students today would empathize. In response to the spread of the novel coronavirus, more than 1,000 colleges and universities in the U.S. have shut down, affecting an estimated 14 million students. The 1918 flu also held a parallel to today’s instances of pandemic-related xenophobia, as the front page of the student newspaper announcing the school’s closure also had an article seizing on wartime anti-German sentiment to argue that the flu, which is believed to have caused its first known case right there in Kansas, “should be called Hun influenza, because it is a slick, sly, tricky and heartless ailment.”

Similar to today, volunteers in the community had stepped up to try to fight the pandemic. Myrtle mentions someone who sounds like a love interest, Ralph, being in “the barracks”; he was likely part of the Student Army Training Corps, which played an active role in helping the university deal with the pandemic. When the manager of the Lawrence movie houses refused to shut down the theaters, the commander of the Training Corps stationed members at entrances to ensure they didn’t open to students. And as demand for medical facilities and doctors outweighed the supply, the Student Army’s barracks were turned into makeshift hospitals, where the university’s medical students came to help.

But what is perhaps most notable about the letter is how little of it is dedicated to the flu. She writes about typical student things: class, schoolwork, her relationship, and how life for her is generally fine.

Stacie Petersen, exhibitions manager and registrar at the World War I Museum, says that Myrtle’s blasé tone shows “an acceptance of what is happening. At this point in time with it being December 1918, the second wave of the flu had been going on now for a couple of months. It’s just what is happening in life.”

By the end, the flu had infected nearly 500 million people, or a third of the world’s population, and caused an estimated 675,000 deaths in the U.S. It is inevitable that those who lived through it experienced waves of fear and grief. And yet, as Mrytle’s letter shows, amid such a long-lasting pandemic, there were moments when life simply went on.

—

Dec. 10, 1918.

Dear Aunt and Family:-

I have thought of you many times but to day [sic] is the first time that I succeeded in finding time to write you a few lines.

Ralph and I are fine, and have not gotten the “flue” [sic] yet altho [sic] it is pretty bad down here at present. It seems to be among the older folks and children. The graded schools and High School is closed here but only a few students of K.U. have it, they thought it was not necessary to close college until they see that it must be done. Heard you folks had it this fall but hope you are all over it and feeling fine. This is beautiful weather for December and to think of such a heavy snow we already had at Thanksgiving seems almost impossible.

Ralph is still in the barracks, he is looking to be discharged most any day altho [sic] they have been waiting for discharging blanks to come, as each must fill out a blank and have a physical examination before he can get out of the army. And the boys here will be pleased to get out too. The boys who do not intend to go to school after being discharged have to drill all day long and the others only have to drill 1 hr. each morning and then they are free the rest of the day until 5:30 for retreat. The barracks here are built in town but they are on K.U. Campus. Dwelling houses on one side of the street and barracks on the other.

I try to see Ralph once each day. If we do not happen to see each other at school, he comes down in the afternoon after class and if he hasn’t time to come, I go to the barracks and he comes out. We rec’d a letter from the folks at home this morn. and the flue [sic] is awful bad around there now. I like it fine down here altho [sic] it is a different life in town than in the country.

I certainly like my school work and time goes so fast, have all my classes in the forenoon but the lessons are so long it takes all P.M. and until 10 P.M. to prepare lessons for next day.

I am as ever your niece, Myrtle

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Anna Purna Kambhampaty at Anna.kambhampaty@time.com