The terror that is gripping Americans due to the coronavirus would be familiar to America’s founding generation. As Noah Webster, then the editor of New York City’s first daily newspaper, wrote to a friend in the fall of 1793, “The melancholy accounts received from you and others of the progress of a fatal disease…excite commiseration in every breast. An alarm is spread over the country.”

The disease was the yellow fever, a virus that attacked the liver and kidneys. This American plague, which got its name because its victims became jaundiced, swept through the nation’s biggest cities a few times between 1793 to 1798. The first outbreak occurred in August of 1793 in Philadelphia, which served as the nation’s capitol from 1790 to 1800. By the middle of that November, the yellow fever would decimate the city, wiping out 5,000 of its 50,000 residents and forcing President Washington and his cabinet to flee to neighboring Germantown. Cool fall temperatures then suddenly stopped this wave of the disease, which, as scientists would determine a century later, was transmitted by mosquitos.

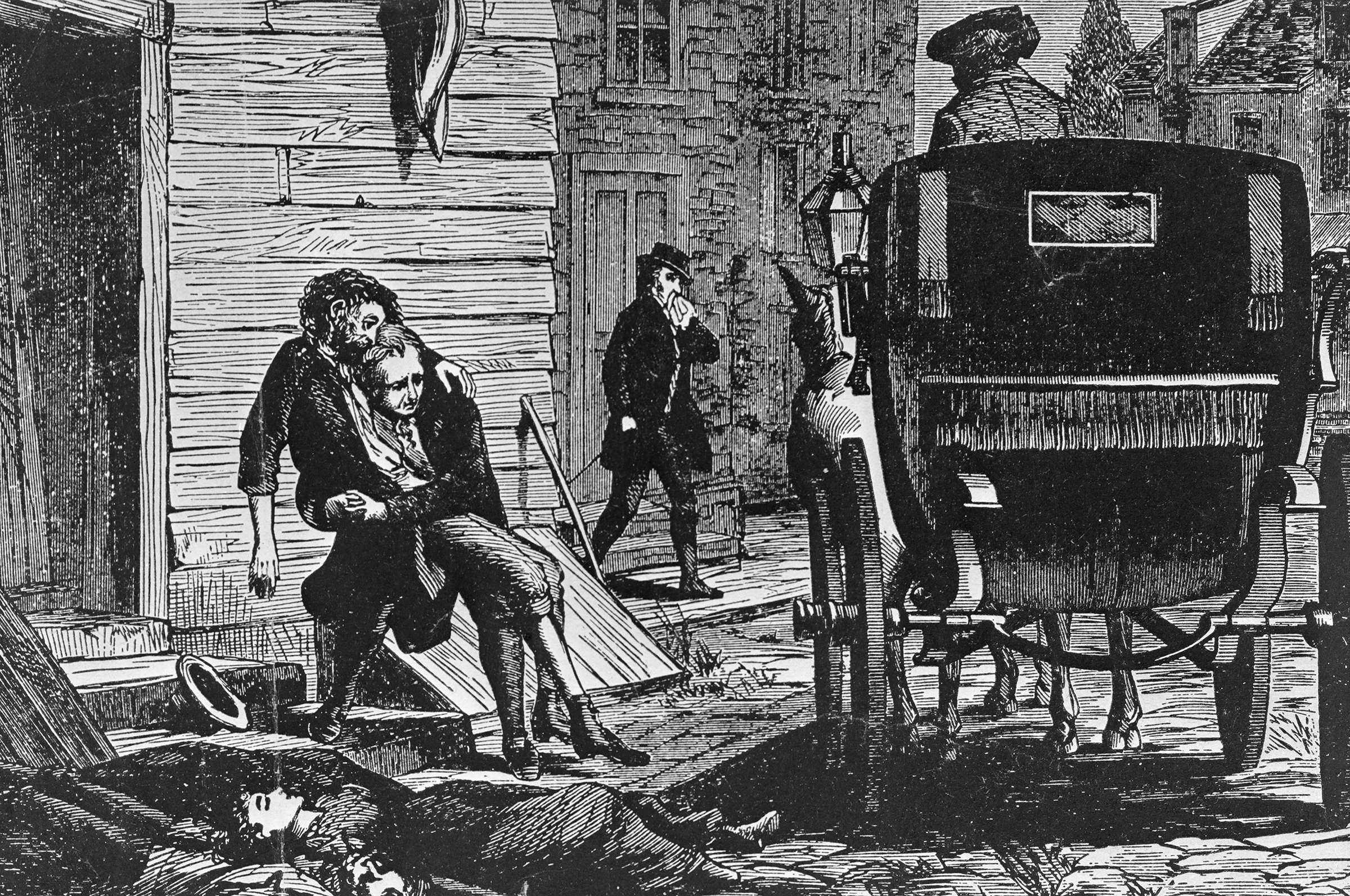

About two years later, New York City was hit particularly hard. Its first recorded patient was Thomas Foster, who sought medical attention from Dr. Malachi Treat, the health officer at the city’s port, on July 6, 1795. As a colleague of Dr. Treat later wrote, Foster’s yellow skin was “covered with purple spots, his mind deranged, his tongue covered with a dry back sordes.” Foster died three days later, and Treat himself was soon gone. By mid-August, two New Yorkers a day were dying, and all afflicted patients were quarantined at Bellevue Hospital. As Webster’s New York neighbor, Dr. Elihu Smith, noted in his diary in September, “The whole city, is in a violent state of alarm on account of the fever. It is the subject of every conversation, at every hour, and in every company.” By late November when this outbreak petered out, 730 New Yorkers had died—the equivalent of about 200,000 today, as the city then had a population of about 40,000

That fall, Webster, who is best known to us today for his monumental dictionary of American English published in 1828, sprang into action. In late October, he published a circular in his paper, The American Minerva, addressed to the physicians in the cities most affected by the fever over the past three years—Philadelphia, New York, Baltimore, Norfolk and New Haven—which asked them to pass on whatever information that they had gathered from their own practices.

This circular served as the basis for the world’s first scientific survey. As Webster argued, given that “we want evidence of facts,” medical professionals needed to work together to understand this public health problem. About a year later, Webster published his findings in a 250-page book, A Collection of Papers on the Subject of the Bilious Fevers, prevalent in the United States for a Few Years Past, which featured eight chapters authored by experts scattered across the country such as Dr. Elihu Smith. Unfortunately, their accounts were short of hard data. Noting that poor immigrants constituted a large percentage of the dead, Smith, hypothesized that “the sudden intermingling of people of various and discordant habits [was] a circumstance favoring the production of the disease.” In contrast, Webster assumed that the cause had something to do with urban grime, arguing that Americans should “pay a double regard to the duties of order, temperance and cleanliness.” But given his empirical leanings, Webster acknowledged that he still needed to gather more data to reach a definitive conclusion.

Partisanship was as pervasive then as it is now, and Webster’s political opponents ridiculed his efforts. Webster’s paper supported the Federalist party of President Washington and Benjamin Franklin Bache, a grandson of Benjamin Franklin, who edited Philadelphia’s Republican paper, attacked his counterpart for self-serving behavior, writing that Webster merely sought for himself “the honor and the glory to triumph over a malady.” In a cruel irony, just three years later, Bache died from the disease at the age of twenty-nine.

In the summer of 1798, the fever came back with a vengeance. As Webster, who had recently moved to New Haven, wrote in his diary, “The disease assumes this year in Philadelphia and New York more of the characteristics of the plague, is contagious and fatal beyond what has been known in America for a century.” By the time frost in early November ended this round of devastation, another 3,400 had died in Philadelphia, 2,000 in New York and 200 in Boston. Included in these totals was New York’s Dr. Elihu Smith, who was just twenty-seven. The fever would return periodically throughout the 19th century, but never again with the same lethal intensity.

At the end of 1798, Webster published a follow-up book, A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases with the Principal Phenomena of the Physical World Which Precede Them and Accompany Them and Observations Deduced from the Facts Stated. The title was a misnomer, as this two-volume treatise clocked in at over 700 pages. Tracing the history of epidemics from biblical accounts to the present, Webster was again forced to conclude that he could not be sure what caused them, observing, “More materials are necessary to enable us to erect a theory of epidemics which shall deserve full confidence. Despite his lack of solid empirical findings, Webster had put the new field of public health on a scientific footing. He had set up a protocol that future medical professionals could follow, which involved gathering as much evidence as possible by pooling together the efforts of numerous experts on the front-lines. As Dr. William Osler, a giant of late 19th century medicine, observed, Webster’s book was “the most important medical work written in this country by a layman.”

As we now hunker down to wait out the current epidemic, we might keep in mind Webster’s observation that deadly diseases induce more than just terror and confusion. “The natural evils that surround us,” Webster wrote in his 1798 treatise, “[also] lay the foundation for the finest feelings of the human heart, compassion and benevolence.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com