A version of this article appeared on the Religion News Service.

More than a third of all American adults attend religious services each week, and some 50% belong to some religious institutions. Based on my research on our religious communities, I believe that even with their doors closed, religious organizations can still be vital partners in transmitting accurate scientific information about the coronavirus.

For the past 15 years, I have been studying the interactions between religious and scientific communities. While we may regard religion and science as at odds in our culture, the fact is that many Americans rely on their religious leaders to guide their attitudes about scientific findings. In my forthcoming book, Why Science and Faith Need Each Other: Eight Shared Values That Move Us Beyond Fear, I show that 34% of evangelical Protestants and about 17% of all Americans say they would consult their religious leader with a question about science, especially science that seems to have moral implications.

The role that faith leaders can play in getting the word out about public health measures is considerable. As the director of Rice University’s Religion and Public Life program, I host a monthly meeting at my home of 30 to 50 Christian, Muslim and Jewish leaders as well civic leaders from around Houston. The constituents of these leaders alone number well over 300,000.

Congregants are more likely to trust not only their leaders, but those who share their faith, particularly people from their own tradition. One of the best things religious leaders can do, then, is partner with those in their congregations who are scientists, physicians or have other expertise on how viruses spread.

There are plenty of religious scientists to draw upon. My work shows, for example, that nearly 25% of scientists working at universities and colleges and 65% of scientists working outside top research universities are Christians. More generally, a little less than 50% of scientists at top U.S. universities have some form of religious identity.

The interaction between religious and scientific communities can sometimes be inhibited by a perception that they don’t share the same worldview. But my research shows that scientists often do their work out of a core value to heal the world around them. In my interviews with religious scientists, I’ve found that many of them feel similarly about their work and their goals, sometimes drawing on the concept of Shalom, a Hebrew word that broadly refers to seeking peace, harmony, well-being and prosperity that result from the flourishing of all creation. One immunologist told me not long ago, “I see science as an amazing tool to intervene on the human condition.”

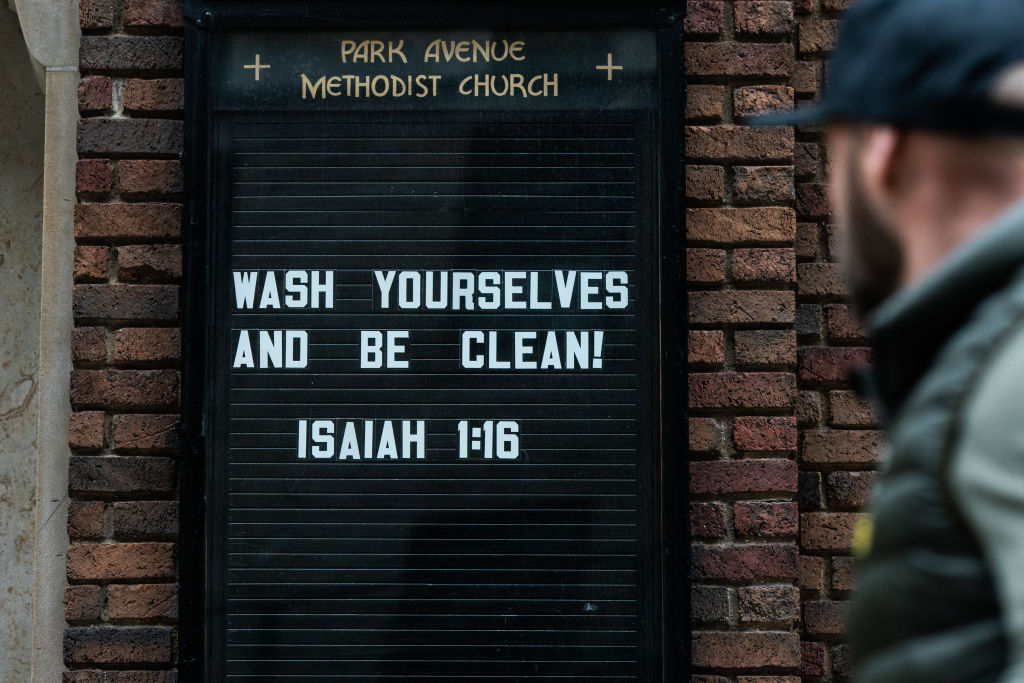

If ever religious and scientific communities need to join together in pursuing wholeness and healing for the world, it’s now. Many studies over the past decade shows us that congregations are often the first and most trusted responders in the most vulnerable communities. People are more likely to turn to their faith communities during times of anxiety and emergency. We need to be sure that religious leaders have accurate and up-to-date scientific and medical information to pass on to their congregations in order to slow the rate of disease spread.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com