On March 18, 1965, the Soviet spacecraft Voshkod-2 launched from its base in Baikonur, in modern day Kazakhstan. On board were two cosmonauts, Alexei Leonov and Pavel Belyayev, who had the important mission of accomplishing mankind’s first spacewalk. It was the golden age of space exploration for the USSR, and the cosmonauts’ mission had a lot riding on it: beyond the obvious scientific and personal stakes, the potential geopolitical consequences were huge.

In the aftermath of World War II, the U.S. and the USSR faced off in a new conflict, the Cold War. Beginning in the late 1950s, space became another dramatic arena for this economic and political competition. The Soviets proved dominant at the onset. On Oct. 4, 1957, a Soviet R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile launched Sputnik (Russian for “traveler”), the world’s first artificial satellite and the first man-made object to be placed into the Earth’s orbit. In 1959, the Soviet space program took another step forward with the launch of Luna 2, the first space probe to hit the moon. In April 1961, the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to orbit Earth, traveling in the capsule-like spacecraft Vostok 1. In response to these Soviet space victories, from 1961 to 1964, NASA’s budget was increased almost 500%, and the American lunar-landing program eventually involved some 34,000 NASA employees and 375,000 employees or industrial and university contractors.

It was the tail end of this Soviet dominance that produced perhaps one of its greatest accomplishments, Leonov’s spacewalk. But that success could have easily become a disaster.

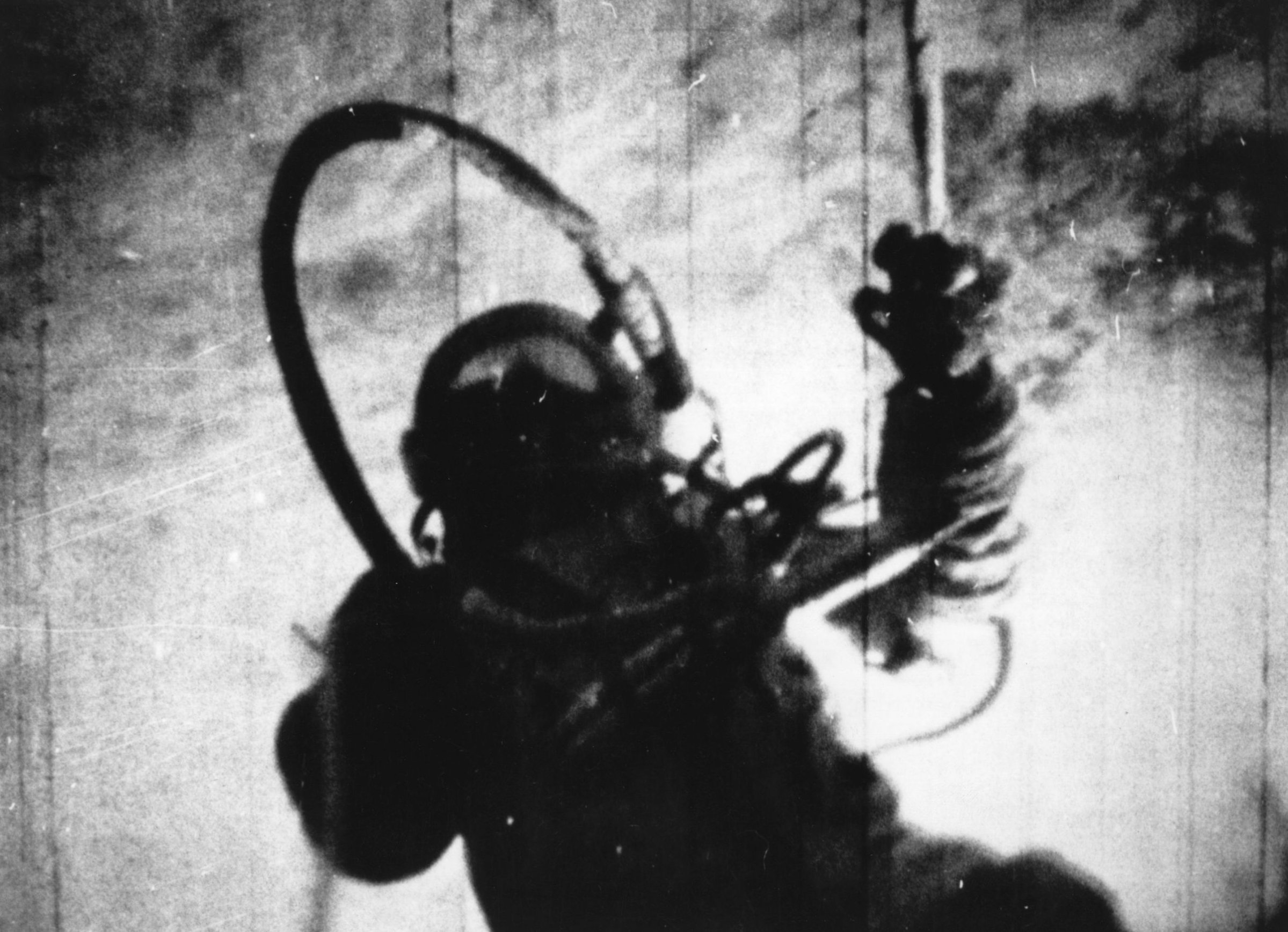

Once in space, Leonov’s partner Belyayev opened the outer airlock on their spacecraft and Leonov floated free for 12 minutes on a tether that was slightly over 16 feet long. Leonov’s actual mission was rather simple in principle. He was to attach a camera to the airlock and document his spacewalk with a still camera that was strapped to his chest. However, he encountered problems from the start.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

His chest-mounted camera could not be used because his spacesuit inflated beyond recognition, making it impossible to access or manipulate the camera. According to historians Rex Hall and David Shayler, Leonov’s core body temperature jumped 35° in under a half of an hour, pushing his body to the edge of heatstroke. In later interviews, Leonov described his condition inside of the suit as sloshing in sweat. Because of the vacuum of space, his spacesuit had not only expanded and stiffened, it was now too large for reentry through the 3.9-foot-wide airlock. Cognizant of eavesdropping on their transmissions, Leonov chose not to report the situation to ground control but to handle it on his own.

He hoped that by slowly opening a valve in the suit to release oxygen, it would depressurize his suit until it was thin enough to squeeze through the hatch and back into the spacecraft. He was right. However, as Leonov himself later recalled, that idea posed an obvious risk: he might not have enough oxygen to breathe. In addition, letting out the air pressure put him at risk of decompression sickness — the bends, a problem deep-sea divers and modern spacewalkers still anticipate and plan for.

Despite his returning to the safety of the spacecraft, their problems had only begun. The spacecraft went into a spin as a result of the inflatable airlock being ejected in preparation for re-entry. Their oxygen levels continued to climb to dangerous levels inside and a single spark could have caused a massive explosion and vaporized the entire spacecraft.

Belyayev and Leonov tried everything they could think of to stabilize the craft, and were eventually able to do so. Their re-entry to Earth was also rife with problems. The craft’s automatic re-entry system failed to fire retro-rockets, which forced them to initiate a manual landing procedure. They veered wildly off-course before re-stabilizing, but their orbital module failed to separate from the landing module, which destabilized the craft even further. They eventually reached solid ground — however, after emerging from the craft they realized, cruelly, they were in a thick forest surrounded by wolves and bears, in a snowstorm. According to Hamish Lindsay, the two men eventually reached safety after a rescue party reached them on the second day.

Despite their success in the face of great odds, the moment marked the end of Soviet dominance in the Space Race. Only two months later, on June 3, 1965, American astronaut Edward White completed the first U.S. spacewalk in Gemini 4. Three years later, December 1968 saw the launch of Apollo 8, the first manned space mission to orbit the moon, from NASA’s massive launch facility on Merritt Island, near Cape Canaveral, Fla. On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 — manned by astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin and Michael Collins — successfully landed on the moon. Armstrong became the first human to walk on the moon’s surface and famously called the moment, “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” But before humanity could leap, we had to learn to spacewalk first, thanks to Voskhod 2 and Leonov’s brazen mission success.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com