Modern-day New Yorkers likely walk past the Postal Telegraph Building at 253 Broadway without a second thought. There are no plaques on the building’s exterior attesting to its significance. There don’t appear to be any in the lobby, either. Visitors are not welcome. The City of New York occupies the building and unless you are on city business, you aren’t allowed past the security check point.

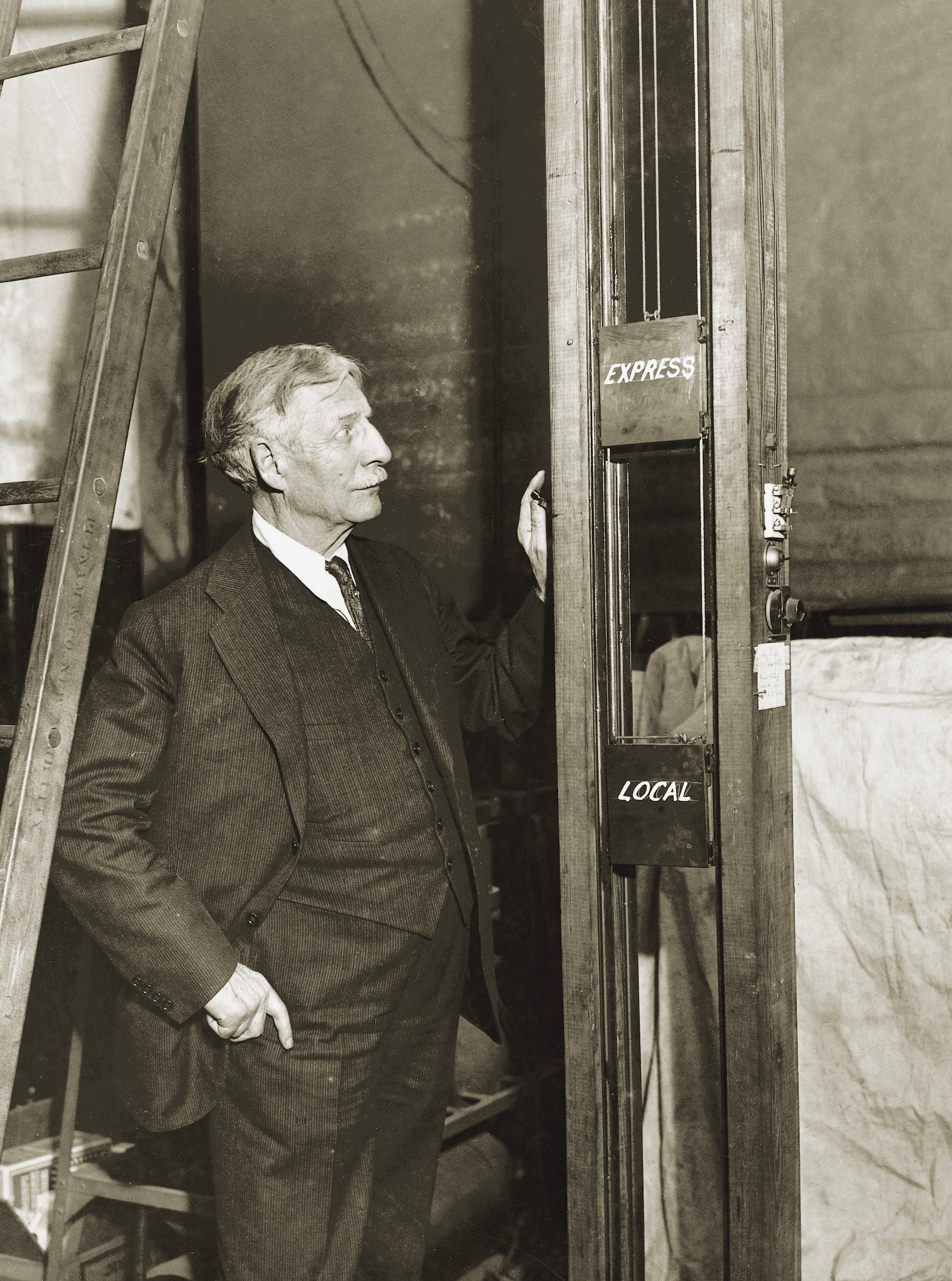

Despite the absence of a plaque, despite being overshadowed by a myriad of other taller buildings in Manhattan, the 14-story-high Postal Telegraph Building deserves special stature in the history of skyscrapers. It was at 253 Broadway that one of the greatest — but least-known — inventors in American history, Frank Sprague, deployed the first bank of electric elevators. By doing so, more than perhaps anyone else, Sprague fueled the rise of the vertical city. Today we think nothing of riding in electric elevators, but those machines allowed cities to house more people on less land than ever before. That increased population density has fostered more human interaction and reduced the impact of cities on the environment. The world’s cities now contain more than half of the global population but, as of 2012, cover less than three percent of its land.

For nearly all of human history, cities were squat things. The height of buildings was limited by people’s willingness to climb stairs. Tall buildings were impractical. Walking up two or three flights of stairs isn’t terrible. Carrying a load of groceries and a screaming infant up four or five flights of steep, dark stairs, is, pardon the pun, another story.

In 1882, when Edison launched the Electric Age with the first central power station on Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan, the tallest structures in New York City were the towers of the Brooklyn Bridge, which was then nearing completion. In 1883, Sprague, a graduate of the Naval Academy, went to work for Edison. But he quit after just 11 months to work on electric motors. As Joseph Cunningham, an author and one of the foremost experts on the early days of electrification in New York City, explains, Sprague’s motors “took industry by storm.” Textile producers and manufacturers used them on cranes, lifts and looms. But Sprague wanted to electrify transportation and in 1887 he signed a contract to install an electric rail system in Richmond, Va.

When he started, Sprague had only a blueprint of the Richmond system. But he had a genius for machines and the tools needed to build and repair them. As one biographer put it, Sprague “was a man for whom machinery wanted to work.” In May 1888, just 12 months after he signed the contract, the Richmond Union Passenger Railway was declared a success. By completing the system in Richmond, Sprague had designed, built and successfully deployed the world’s first full-scale commercial electric railway. Shortly after evaluating Sprague’s system in Richmond, the city of Boston ordered the world’s second electric rail system. By 1905, some 20,000 miles of streetcar tracks had been laid in the United States. Today, electric rail systems are ubiquitous in the world’s biggest cities, delivering millions of passengers quickly and efficiently.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

After figuring out how to use his electric motors to move passengers across the horizon, Sprague focused on moving them skyward. In 1892, he formed the Sprague Electric Elevator Company and, shortly afterward, won a contract to install his electric elevators in the Postal Telegraph building. Sprague had to prove that his elevators were superior to the slow, balky hydraulic elevators that dominated the market. The deal was dangerously one-sided. If his elevators didn’t work as promised, the contract required Sprague to rip them out and replace them, at his cost.

Two years later, when the Postal Telegraph Building was finished, Sprague’s elevators worked perfectly. In fact, they operated at speeds comparable to those of modern-day elevators.

That speed was key to their success. In cities, we want to travel as fast — or faster — when we travel vertically as we do while traveling across the landscape. People in cities are in a hurry. A New York minute doesn’t last very long. In the 1990s, Italian physicist Cesare Marchetti showed that our commuting patterns aren’t necessarily determined by distance, but by time. That is, we don’t think much about how far we are going, as we do about how long it will take us to get there. Our travel-time constraints also apply to vertical transportation. Sprague’s electric elevators at the Postal Telegraph Building proved that vertical transportation could be just as fast as traveling by foot on level ground. That was a crucial turning point in the history of skyscrapers.

In 1913, on a site two blocks south of the Postal Telegraph Building, the Woolworth Building was completed to a height of 792 feet. Dubbed the “cathedral of commerce,” it boasted 60 stories and gained renown for its high-speed electric elevators, which provided both local and express service to visitors and tenants. At the time it was completed, the Woolworth building was the tallest building in the world, a distinction it held until 1930.

Since then, New York City has grown an entire forest of skyscrapers. In 2017, a group of economists estimated that the land in New York City — repeat, just the land, not the buildings — was worth about $2.5 trillion. That land is worth trillions because of what can be built on it, or rather, what can be built above it. Without electric elevators, all that vertical space would be worth far less. Today, nearly a century after his death in 1934, few people know Sprague’s name or how he shaped our cities. We accept the reality of troposphere-scratching structures like the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which has 57 elevators serving 163 floors — and which will soon be eclipsed by the Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia, which will stand a full one kilometer tall. By electrifying transportation in two dimensions — across the landscape and toward the heavens — Frank Sprague deserves to be recognized not only as one the great inventors of the Electric Age, but as one of the pioneers of the modern vertical city.

This essay is adapted from Robert Bryce’s new book, A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations published March 10 by PublicAffairs.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com