The reign of the world’s oldest prime minister came to a surprising end Sunday when Malaysia swore in a new leader following a week of political turmoil.

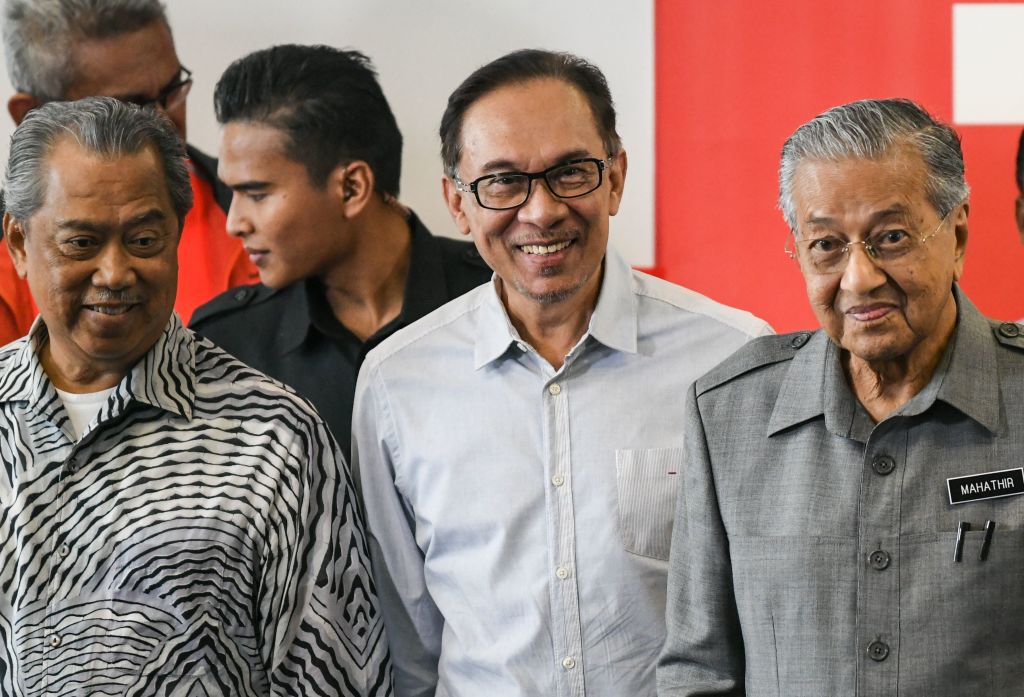

What began as infighting over succession and rumored mutiny ended with conservative politician Muhyiddin Yassin named prime minister. “I feel betrayed,” Malaysia’s ousted leader, 94-year-old Mahathir Mohamad said.

In all the horse trading, power changed hands from the most multi-ethnic, liberal-minded government Malaysia has known, to a ruling bloc that panders to the Malay-Muslim majority. Mahathir has accused the new governing coalition of partnering with kleptocrats embroiled in one of the world’s greatest embezzlement scandals, saying he refuses to work with graft-tainted politicians unless they are “proven clean,” while perhaps “Muhyiddin is more relaxed towards this approach.” The shift stands to extinguish one of Asia’s few democratic bright spots amid a global slide toward illiberalism.

“I doubt reform (or even integrity) is a priority,” Ambiga Sreenevasan, a Malaysian lawyer and human rights advocate, wrote to TIME about the new government.

This latest transition dislodges Malaysia from the reform trajectory set in motion after a stunning election upset in 2018. Two years ago, Mahathir, Malaysia’s longest serving prime minister, staged a comeback to wrest power away from his former party, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), which had ruled since independence in 1957.

Seeking to unseat his own protégé—who was accused of overseeing the looting of billions from state investment fund 1MDB—Mahathir allied with opposition figures he had once persecuted. But the motley coalition that finally managed to topple UMNO made for strange bedfellows. Freighted with ideological, religious and ethnic divisions, Pakatan Harapan (Alliance of Hope) finally collapsed last week, pitching the Southeast Asian country into chaos.

After canvassing lawmakers, the king eventually picked Muhyiddin, a 72-year-old Malay nationalist and former UMNO leader, to steer the country. It was a strange end to a week of opaque political machinations, with allegiances seemingly shifting by the minute.

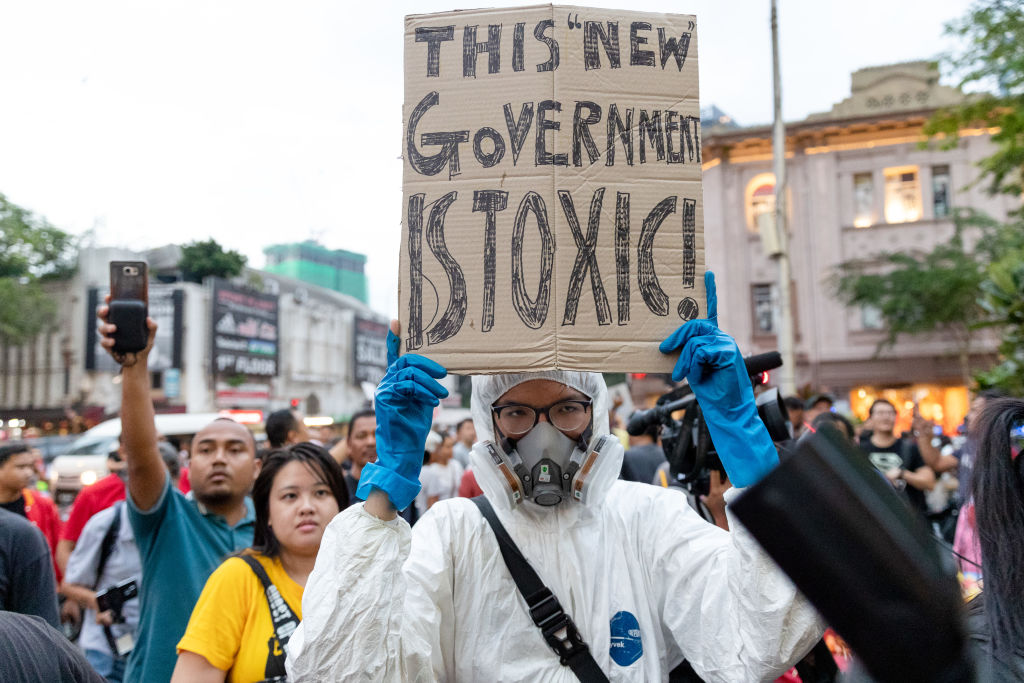

Few believe the dust-up has fully resolved. Street protests have erupted, and a possible no confidence vote in parliament looms. But if Muhyiddin and his allies remain in the driver’s seat many analysts fear Malaysia’s brief dalliance with democratic reform is over, and the days of race-based politics have returned.

Ethnic tensions

When Muhyiddin, a conservative Muslim from the Malay heartland, first heard he was picked for the premiership, he dropped to the floor and prayed. A video capturing his piety circulated on social media.

The move didn’t surprise observers who point out that Muhyiddin, who once said he is “Malay first,” Malaysian second, created a coalition invested in the notion of Malay-Muslim supremacy.

“He is likely to steer the country in a more conservative, and a more Malay, Islamic way,” says James Chin, director of the Asia Institute Tasmania at the University of Tasmania.

For decades, the ethnic Malays who make up around 69% of Malaysia’s population have enjoyed extensive affirmative action programs.

During Mahathir’s previous tenure as prime minister, from 1981 to 2003, government policies catered to the majority Malay population, seeking to buoy their economic status, even as critics said it fueled race-based cronyism.

After the 2018 election coup, the administration that took over was unprecedented in its diversity, with Sikhs, ethnic Chinese and Tamil Malaysians in the cabinet. More than 40% of the ministers were non-Malay, compared with about 20% under the toppled regime. But such an inclusive, multi-ethnic government exacerbated many Malays’ fears of losing their preferential treatment.

“[Mahathir’s government was] actually pouring more money into the Malay agenda,” says Chin. “But they had a perception problem.”

In particular, the appointment of ethnically Chinese Malaysian Lim Guan Eng as finance minister stoked concern that he would repeal the subsidies and special privileges that ensure Malays’ dominance. And the selection of Tommy Thomas as the first non-Muslim, non-Malay attorney general riled religious radicals since his portfolio included the country’s Islamic court system.

A Malay-first coalition

Muhyiddin capitalized on this simmering resentment and forged a Malay-centric coalition that largely precludes minorities.

The new prime minister is working with parties that tend “to fall back on race and religion to maintain and gain ground,” says Serina Abdul Rahman, a visiting fellow under the Malaysia program at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

The son of a well-known cleric, Muhyiddin found support in Malaysia’s hardline Muslim party, the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS), and gave it a role in the federal government for the first time in over four decades. PAS has proposed implementing a strict Islamic penal code on Muslims, including harsh punishments like stoning adulterers.

He has also reunited with the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), the Malay nationalist party that ruled Malaysia for more than six decades and was voted out two years ago. Formerly a deputy prime minister, Muhyiddin was sacked after criticizing UMNO leader and then-premier Najib Razak’s handling of the 1MDB fund.

Muhyiddin’s newfound willingness to build an alliance with UMNO members has fueled concern that the ongoing corruption trials may be derailed. If members of the new ruling bloc are found guilty, some analysts suggest Muhyiddin could lose his razor-thin parliamentary majority.

The tarnished UMNO party’s return to power has prompted demonstrations, with protesters calling it a “backdoor government.”

Power struggle

While ethnic and religious tensions underlie the recent power play, it was at least partially triggered by Mahathir’s promise to eventually cede power to his rival turned ally Anwar Ibrahim.

“The key to much of what is going on is the unresolved issue of who will succeed Mahathir,” Bridget Welsh, an honorary research associate at the Asia Institute of the University of Nottingham Malaysia, recently told the Asia Society. “There are many people across the political spectrum who are interested in making sure that the successor will not be Anwar.”

The last time Anwar was in government with Mahathir, as the deputy prime minister and likely successor, he was sacked and imprisoned on sodomy charges he maintains were politically motivated. Mahathir obtained a pardon for his onetime nemesis a week after winning the 2018 election, but never cemented an exact timeline for handing over leadership of the government.

While Mahathir recently floated staying in power until the end of his term, Anwar, 72, publicly said a transition would take place in May 2020.

But the idea of Anwar assuming power unnerved Malay nationalists, both because of his sodomy trials and his insistence that the country needs to move away from race-based economic policies.

On Saturday, Anwar said he would once again shelve his ambitions to lead Malaysia. “I will be taking a step back,” he told reporters, “so that we can avoid the country being further dragged into this power struggle and into an old system which has been rejected by the people.”

Ever the wily statesman, Mahathir has not yet given up trying to claw back power. He called for an urgent parliamentary vote against the new prime minister once parliament reconvenes in May. He claims Muhyiddin lacks the majority’s support. If so, Malaysia’s game of thrones may not be over.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Laignee Barron at Laignee.Barron@time.com