Suppose, Mike Bloomberg is telling me, there’s been some sort of explosion. First of all, you want to be ready. “The first thing is preparation,” he says. “You don’t ever want to be in a situation where you have to develop the plan as you go along.”

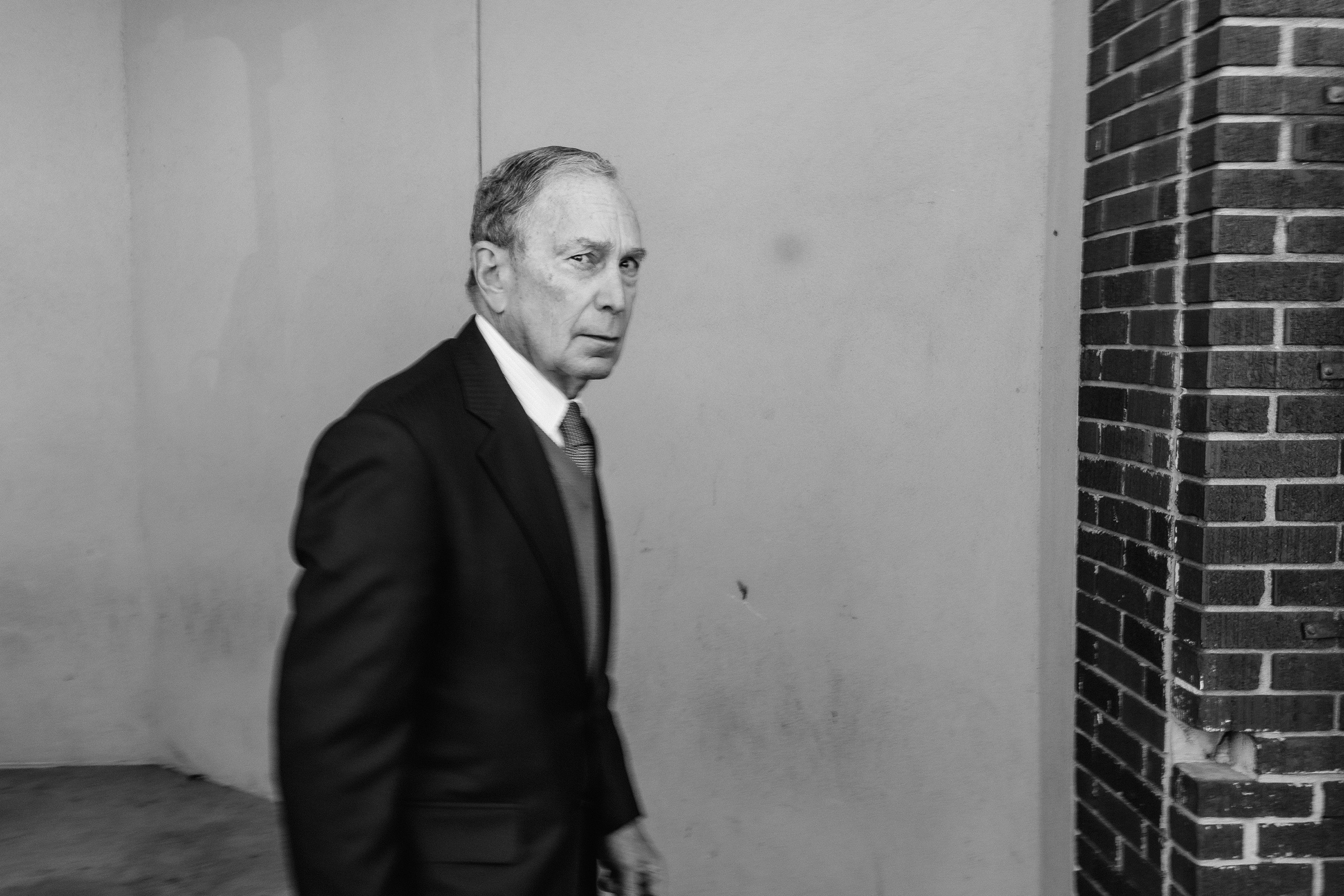

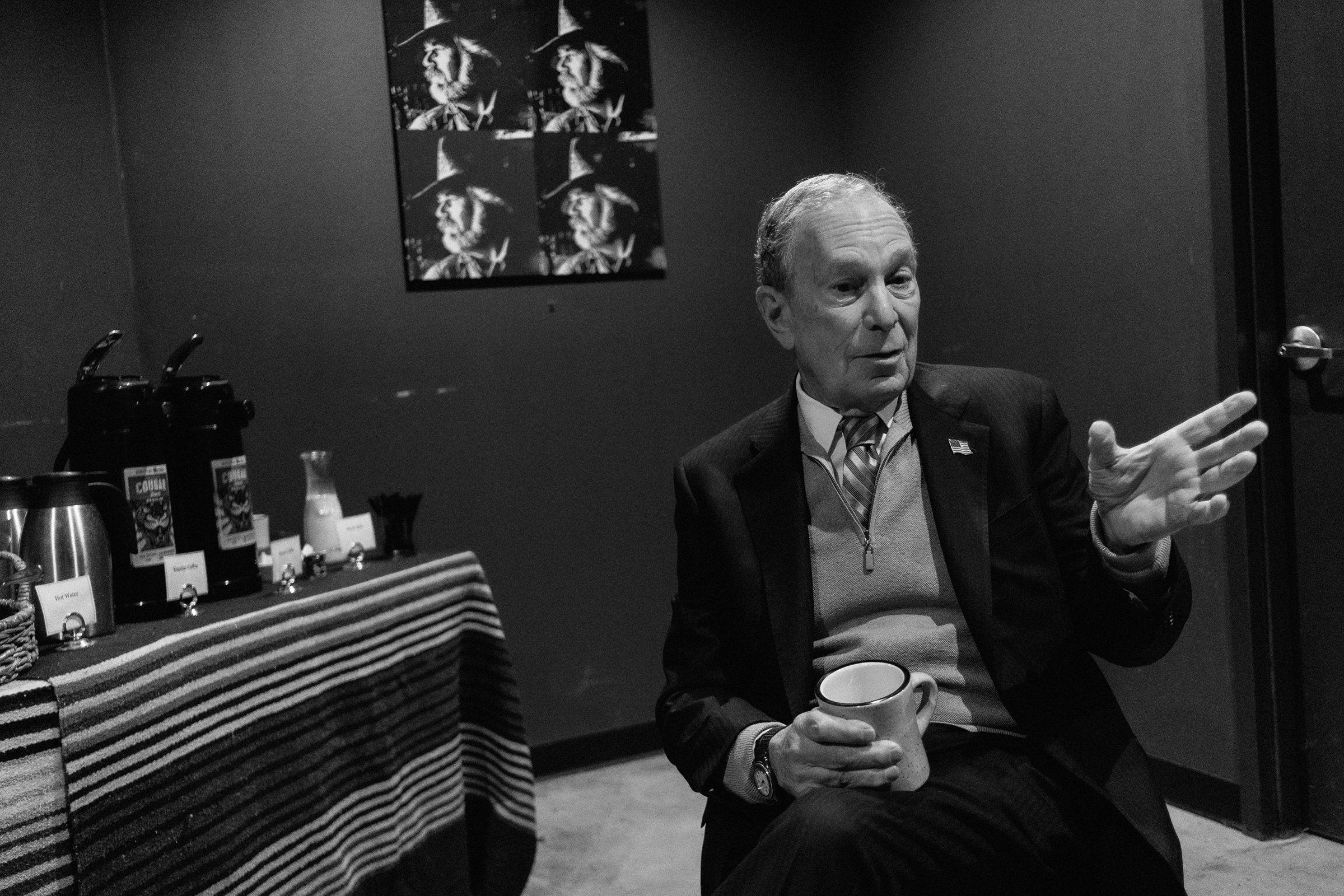

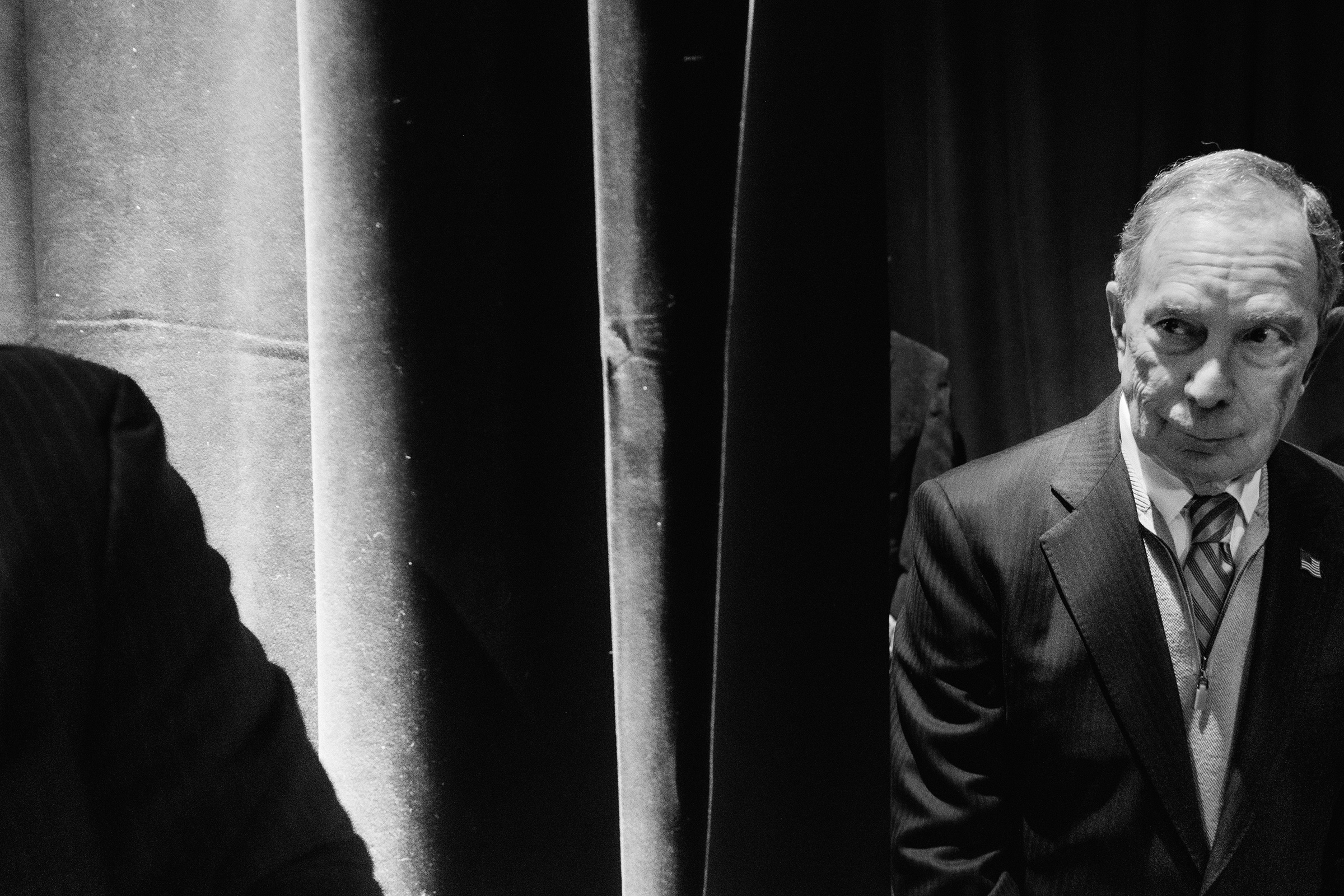

The 78-year-old billionaire and former New York mayor is in Houston on Feb. 27, backstage from the campaign event where he’s just delivered his stump speech to a couple hundred locals. It’s not a bad crowd for a weekday morning, though the free food and T-shirts surely didn’t hurt. Bloomberg is perched on a small wooden chair; he has a slightly feline way of sitting—drawing inward, legs crossed and arms pulled close. Poised and self-contained, he’s the opposite of the dreaded “manspreader.”

We’re talking about one of his favorite topics: how to handle a crisis. It’s a subject that has become newly relevant lately with the worldwide explosion of coronavirus, which has killed at least 3,000 worldwide and is now spreading in the U.S. Bloomberg has deep experience responding to crises, from the Sept. 11 attacks, which took place during his first mayoral run, to Superstorm Sandy, which slammed New York near the end of his 12 years in office, flooding subway tunnels, cutting off power and causing dozens of deaths and billions in damage. Cool-headed and decisive, Bloomberg thrives in such urgent situations, allies say. In the words of his longtime partner Diana Taylor, “Michael is at his best when he is in the middle of a hurricane.”

Crisis management has become the cornerstone of his presidential pitch. It’s the topline of his stump speech and the subject of a three-minute commercial, styled like a presidential address, that his campaign aired on major networks on March 1, 48 hours before the Super Tuesday polls are set to close. Trump, Bloomberg argues, has utterly failed as a crisis manager, ignoring months of briefings on the coronavirus, failing to staff the White House team in charge of pandemic response and proposing cuts to the Centers for Disease Control. “The mayor, or in this case the president—you have to stand up and be the leader. There’s no argument about that. But you have to be knowledgeable,” Bloomberg tells me. “The mayor’s job was to provide people with the confidence that adults were in charge and that they would be informed. You don’t go out and get them to be overexcited, and you also don’t want them to be complacent. There’s a balance, and you get it by practicing. And that’s what we don’t have in the White House now.”

Nobody knows how serious the pandemic will be or whether the Administration will bungle it. Not everyone gave Bloomberg great marks for handling crises, either; his approval rating was middling when he left office in 2013. But more than any policy agenda or vision, the image of Bloomberg as world-class fixer is the selling point of his campaign. His speeches double as management seminars, delivered to eager audiences of educated, white-collar moderates. More than mere competence, he’s hawking an unflappable professionalism that contrasts starkly with Trump, renders moot his poor debate performances (he’s a doer, not a talker!), and offers an escape from his adopted party’s ideological battles. What if the next president just, you know, did a good job?

But it’s a very different kind of mess that Bloomberg is now trying to fix: the fractious Democratic presidential primary. In late November, with the field devolving into an acrimonious melee and Senator Bernie Sanders emerging as a front-runner for the nomination, Bloomberg, who’d long flirted with a presidential run, reversed his prior decision to stay out of the race. “I watched and I thought, ‘These people are all going to lose to Donald Trump. He’s much tougher,’” Bloomberg tells me.

He blazed into the race with his usual combination of relentless drive and bottomless pockets, spending more than half a billion dollars of his $60 billion fortune on a campaign as unprecedented as it is overwhelming. Other campaigns buzz about the Bloomberg team’s lavish accoutrements, from $6,000 per month for low-level organizers to free iPhones and furnished apartments in Manhattan for staff at New York HQ. His TV ad spending is quadruple that of his remaining rivals combined. The would-be Bloomberg juggernaut combines a supersized version of rivals’ campaign tactics—more than 200 field offices and 2,400 staff in 43 states and territories—with more unconventional plays: paying social-media influencers for jokey Instagram posts; paying “digital organizers” (that is, regular people) to text their friends.

On March 3, Bloomberg’s big bet will be called. His name will be on the primary ballot for the first time as 15 states and territories vote and about one-third of the total delegates are awarded. Sanders holds a delegate lead over a surging Joe Biden, and Bloomberg’s debate flops have some Democrats accusing him of being an obstacle rather than savior, contributing to the clog of moderate contenders that’s preventing Democrats from consolidating around a non-Sanders candidate. Unlike when he was mayor, Bloomberg can’t order those in the path of his blitz to evacuate—not that he hasn’t tried. In an act of breathtaking hubris, his aides urged candidates who’d been running for many months to get out of the race to make way for Bloomberg, who has yet to contest a single primary.

Bloomberg scoffs at the notion that he’s making the situation worse, contending that he can hardly be considered a spoiler when he hasn’t even been on the ballot in the contests that have produced the current muddle. “Today our internal polls show us at 18%. Now, is it at 24%, where our polls show Bernie? No, but we still have some time,” he tells me. “There’s plenty of other states and maybe nobody will get a majority. And if nobody has a majority, then you go to a convention and they have a democratic process and some rules of how you decide. And we’ll see what happens.”

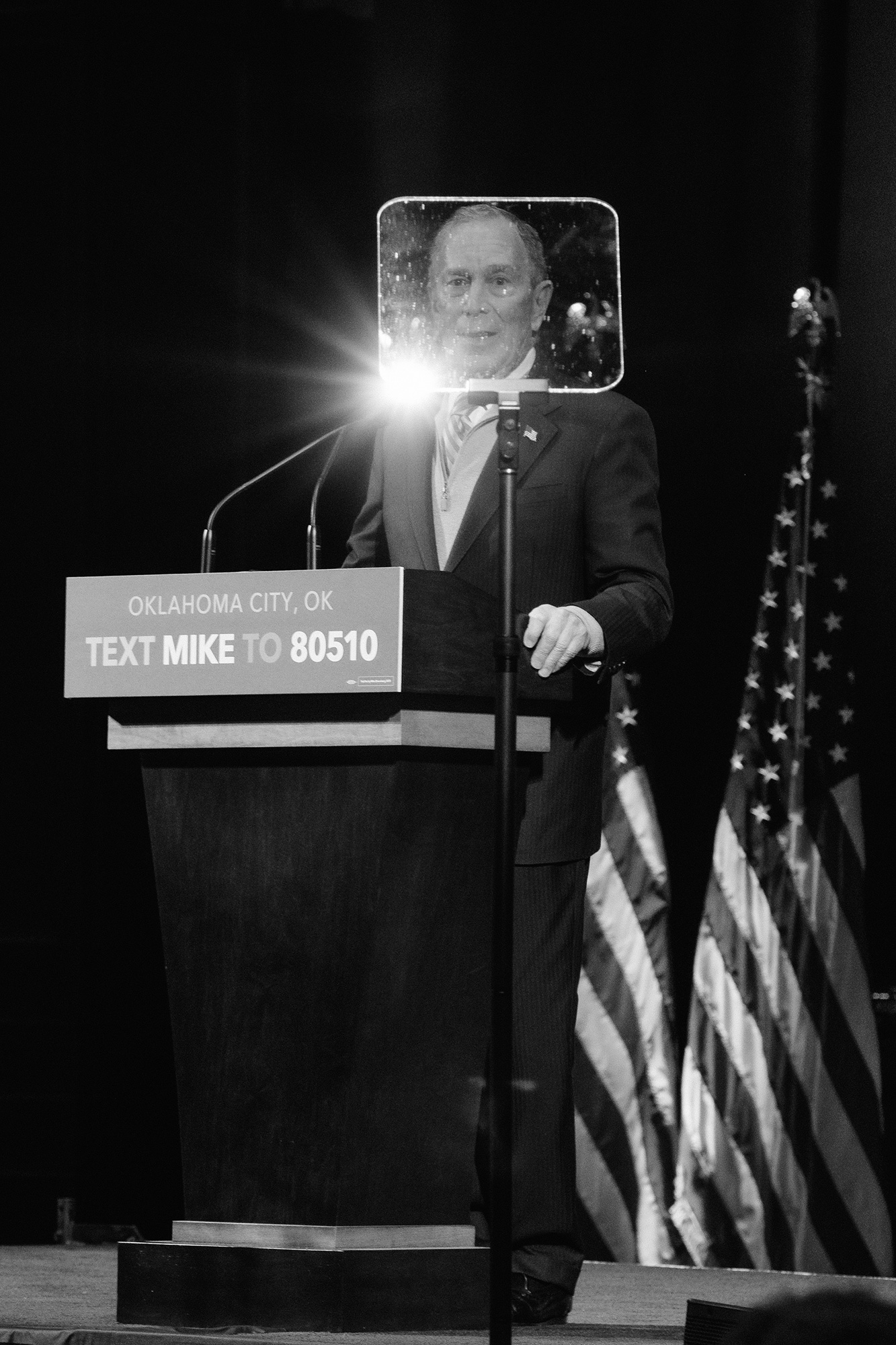

From Houston, Bloomberg and his entourage fly to Oklahoma City, where a few hundred people are filtering into another impeccably staged event venue. Bloomberg reads the same speech from teleprompters at each stop, with a couple of canned lines about local traffic problems or college rivalries thrown in. He races through it in a singsong lilt, pausing for laughter that never comes at lines he thinks are funny. (Even his staff can’t understand why he’s so amused every time he says, “If you’re looking for a candidate that talks turkey—”, an idiom that’s not remotely a joke.) He does not, as Trump has charged, stand on a box, but he does use an identical lectern at every appearance, a two-toned wooden platform that conveniently hits the 5-foot-8 pol right at his waistline.

Some people take free “I Like Mike” T-shirts on the way in or stop at the catering tables. They’re stocked with red, white and blue donuts; “MB 2020” sugar cookies in both round and rectangular formats; fresh fruit; pretzel bites and cheesy dip; and water infused with your choice of orange or lemon-lime. The spread is unusual for campaigns, which typically hoard their resources to spend on things normal candidates have to worry about, like paying for ads. A younger Bloomberg once said of the lunches Bloomberg LP provides its employees: “If people believe it’s really free, you don’t understand the business model.”

Paul Garrett, a 61-year-old financial adviser and political independent, tells me he’s looking for a candidate who will be an effective president, and has narrowed his choices down to Bloomberg and Amy Klobuchar. (Klobuchar dropped out of the race on March 2, squeezed partly by Bloomberg’s spending.) He didn’t watch much of the “so-called debates,” which he mostly considered useless shoutfests, and is not put off by Bloomberg being a billionaire. “I do not have biases against successful people,” he says.

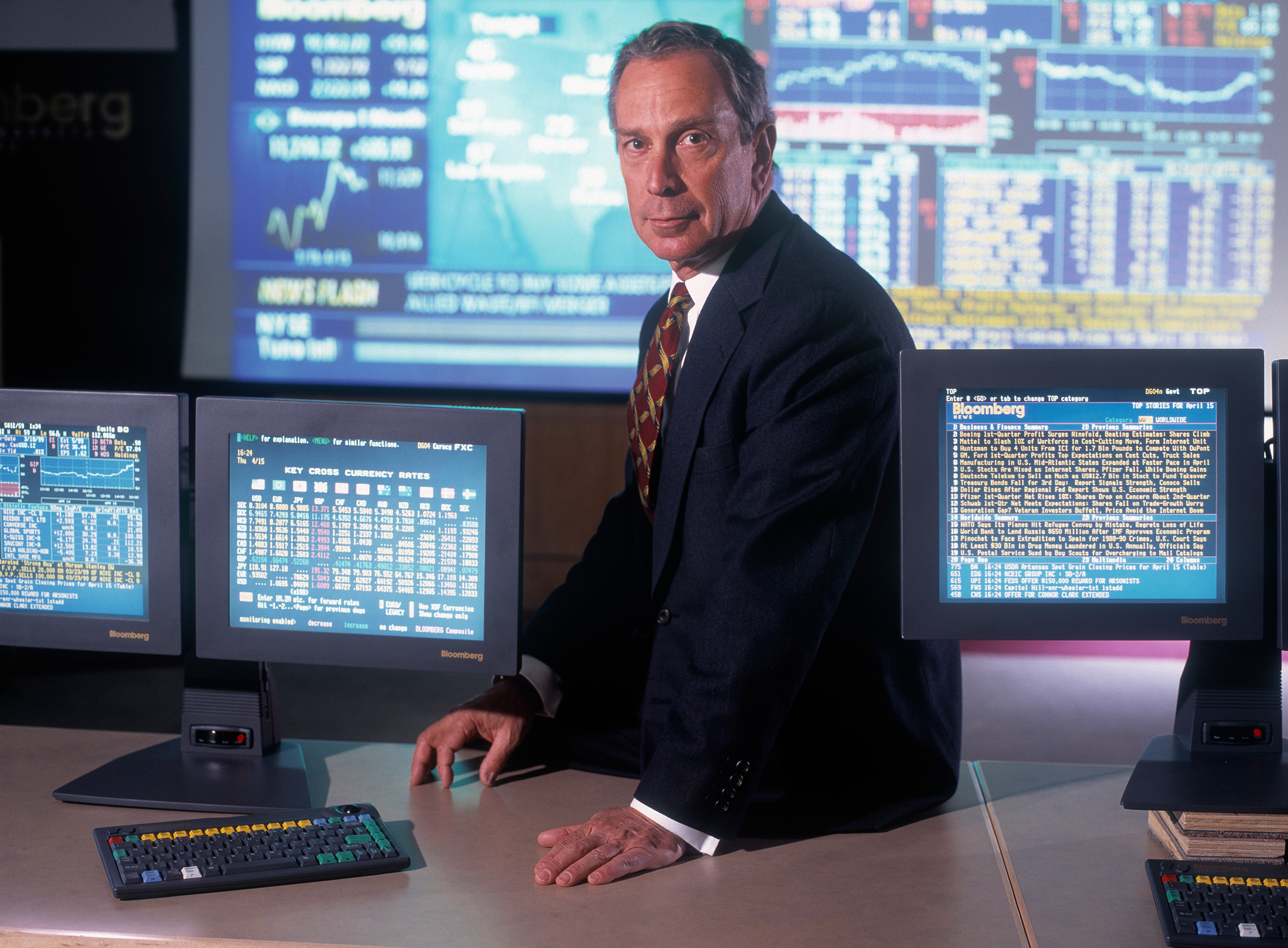

Like many successful people, Bloomberg, having made a fortune running his company that sold computer terminals to Wall Street, decided the next step was to run something even bigger. His political career was forged in crisis. On Sept. 11, 2001, he was a long-shot Republican candidate for mayor of overwhelmingly Democratic New York City. It was the day of the mayoral primary, and he had just cast his ballot for himself and returned to his campaign headquarters when the first plane hit, recalls Jarrod Bernstein, who worked for Bloomberg at the time and would go on to serve in his administration and the Obama White House.

A licensed pilot, Bloomberg immediately sensed that what was happening was not an accident. “He got very calm and focused,” Bernstein says. “I remember him saying, in the first two or three minutes: I need to know where my people are. He immediately wanted an accounting of the people he was responsible for.”

Taylor, Bloomberg’s girlfriend, remembers seeing the planes hit on the news and rushing down to the campaign office. “I’ll never forget, he was sitting at his desk,” she says. “Everyone was watching the TVs and what was happening downtown. He looked up at me and said, ‘I guess we’re not having a party tonight.’”

The primary was rescheduled. After he won it, Bloomberg pivoted off the tragedy in the general election, arguing that the city needed the kind of strong executive experience he could provide. Many observers credited 9/11 for his narrow victory. And while then-mayor Rudy Giuliani is most remembered for his leadership of the city during the attacks, it was Bloomberg who was responsible for dealing with much of the aftermath.

The pile had barely stopped smoldering when he became mayor four months after the planes hit. Ground Zero presented a vast array of short- and long-term problems. He had to oversee the cleanup, provide aid and comfort to the victims’ families, restore the city’s morale, get business going again and participate in discussions about what to do with the site. Giuliani had been laser-focused on the rescue effort, but Bloomberg realized there were other issues too, says Madelyn Wils, who was chair of lower Manhattan’s community board at the time.

People in lower Manhattan had lost their homes and businesses, but until Bloomberg took office, the city ignored them, Wils says. “There was an enormous shift when Bloomberg came in,” she says. “Immediately, he started to meet with people in the community. He was very calm and productive and made sure that the community and businesses were being heard.” Bloomberg refereed contentious disputes over the future of the site, she says, expressing his view that Giuliani’s proposal for a 16-acre memorial would turn lower Manhattan into a “cemetery” and embracing plans for a smaller memorial. “He found a way to take care of everyone,” says Wils.

Bloomberg also fought to improve the city’s counterterrorism preparedness and lobbied Congress for funds to monitor and treat the health issues sustained by first responders. He oversaw a secret NYPD counterterrorism program that surveilled Muslims in the city, which he still defends against charges it was discriminatory.

The 9/11 aftermath was only the first of a series of crises that studded Bloomberg’s tenure. There was a shooting in the city council chamber, an anthrax scare, a Staten Island ferry crash that killed 11. In 2003, a citywide blackout had residents temporarily convinced that another terror attack was under way.

The financial crash of 2008 was a catastrophe of a different sort, but it hit the city hard. Bloomberg takes credit for steering New York out of it, in part by drawing on his elite business contacts. But critics charge that he was too fixated on Wall Street’s challenges to see that Main Street was suffering, too. “The city was facing a massive budget crisis, and instead of supporting more taxes on the wealthy to fill the budget gaps, he pushed through a massive cut to schools, housing and social services,” says Jonathan Westin, director of the community-activist group New York Communities for Change.

It was local austerity as much as national malaise that fueled the Occupy Wall Street protests of 2011, Westin says—protests to which Bloomberg responded not with sympathy but with mass arrests and a midnight police raid to clear Zuccotti Park. “When Occupy rose up in response, his reaction was to crush it.”

As he had done with 9/11 and is doing now with coronavirus, Bloomberg seized on the recession as a political opportunity. He used the downturn to argue that he should stay in office beyond his two-term limit. After a contentious political battle, he got the city council to amend the city charter to allow him to serve a third term—part of what critics argue is a pattern of changing the rules to get his way when it suits him.

Narrowly winning a third term with the help of $100 million in campaign spending, Bloomberg was increasingly assailed for turning Manhattan into a playground for the rich. He spent many weekends jetting off to play golf at his estate in Bermuda, and sometimes violated city airspace rules by taking off in his personal helicopter. He was apparently out of town when a major snowstorm hit in late 2010. This time the city’s response, which included plowing Manhattan streets before those in the outer boroughs, was panned. Bloomberg initially insisted everything was fine because Broadway shows were still going on, but later expressed regret.

Nine months later, Hurricane Irene barreled in from the Atlantic. New York had been one of many cities to take stock of their hurricane preparedness after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005. Bloomberg personally insisted that this be done, even though New York hadn’t been hit by a major hurricane since 1938, says Cas Holloway, who served as deputy mayor for operations. The administration mobilized for Irene, working with the state to order evacuations and shut down the subway system, but the storm ended up petering out before it got to New York City. Holloway says this allowed the city to test-run its hurricane protocols, which proved useful when a bigger storm began heading toward the city the following year.

Superstorm Sandy hit with force, drenching the region and flooding neighborhoods. “There were so many issues—the flooding of the tunnels going into the city, issues with power outages, issues with providing health and welfare assistance to those rendered homeless by the hurricane,” says Janet Napolitano, who was then secretary of homeland security, the federal department that includes FEMA. “It was amazing how quickly New York City got back on its feet and became operational. Literally half the city was in the dark, and they had the lights back on in Manhattan within 24 hours.”

Bloomberg allies say Sandy showcased the mayor at his best. His insistence on preparedness paid off. The credibility he’d amassed with New Yorkers meant that when he ordered evacuations, most people listened. His management approach, which stresses empowering teams of people to rely on data to creatively solve problems, allowed people to customize solutions. For example, Bloomberg quickly determined that the usual solution to hurricane displacement, temporary housing, wouldn’t work in New York City and instead focused his administration on repairing people’s homes as quickly as possible. “He said, ‘There’s no room for trailers in New York City, we’ve got to get people back in their homes,’” Holloway says. “We repaired 11,000 multi-family and single-family homes in 110 days.” People talk about Bloomberg as if he were himself a computer, taking in data and spitting out decisions, emotionless and perfectly efficient—a walking, talking Bloomberg terminal.

Bloomberg was criticized after he left office for the bottlenecks in long-term Sandy aid that followed, and for devoting resources to long-term climate planning when the short-term problems still weren’t resolved. But prevention is really the best crisis management, argues Noah Kroloff, who was Napolitano’s chief of staff. “Not everyone has that natural instinct to lead, to immediately jump in and start solving problems,” he says.

This is the skill set Bloomberg says Trump is missing—with potentially deadly consequences. Rather than talking about the price tag of the coronavirus response, Trump should be laser-focused on making sense of imperfect information and communicating clearly with the public, Bloomberg tells me. “We ran simulations all the time and what-ifs,” he says. “And so when we did have a crisis, the teams were ready. The teams knew each other. They all coordinated. There wasn’t everybody going in a different direction.”

Bloomberg’s last stop of the day is in Bentonville, Ark., home of Wal-Mart, where an overflow crowd streams through the doors past a ragged handful of Sanders-supporting protesters. They’re shouting, “Classy Klan rally!” and “No blue Trump!” As she passes them, one woman remarks to her companion, “Those are my son’s friends!”

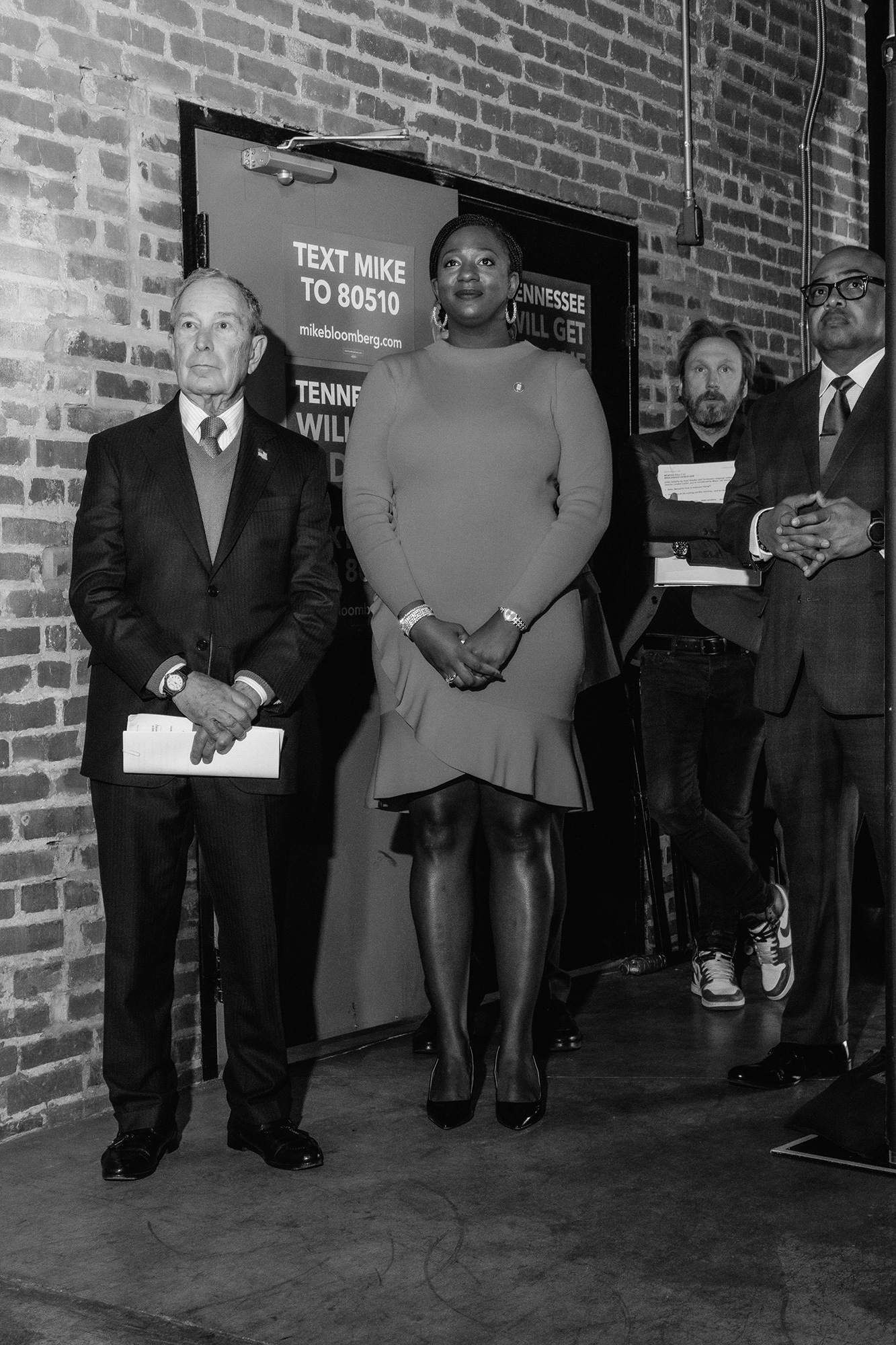

The crowds at Bloomberg’s events are often racially diverse but economically homogenous—people with graduate and professional degrees, lawyers and bankers, CEOs and executive vice-presidents. At one Bloomberg rally, I meet a former senior adviser with the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq; at another, the labor director for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

The people attracted to Bloomberg’s candidacy are achievers and doers; they’re people who feel they’ve earned their success. These aren’t the kind of people who feel personally screwed by the system as currently structured and yearn to overthrow it. But they’re looking for an alternative to Trump, and many are downright alarmed by what’s happening to their country. “We’ve got to find somebody,” Mary Kennedy, a 75-year-old retiree who’s attending the Bentonville event with her husband, tells me, sounding near-frantic. “Our country’s in a mess. Everything’s been gutted. I don’t know how anyone could put it back together.”

From Sanders’s call for political revolution to Biden’s campaign theme of a twilight struggle for the nation’s soul, everyone running in 2020 seems to see a nation in crisis—everyone, that is, except the would-be crisis-manager-in-chief.

When I interviewed Bloomberg, I expected he would pivot from his crisis-management pitch to make the argument that he was thus suited to tackle the larger cataclysm Trump has caused for American democracy. But he didn’t see it that way. To him, crises are discrete situations, not abstract states of being. “We have a potential crisis from the virus,” he says dispassionately. “We have a White House that’s dysfunctional—there’s a crisis there. The stock markets, you could argue that we’re in crisis, although I think that’s a small thing compared to these other things.”

Crisis management, to Bloomberg, is a specific aspect of a chief executive’s job. In his mind, America is still basically OK. “It’s still the country—people vote with their feet, less so maybe than before—this is where you want to go,” he says. “We have an enormous amount to be proud of. We still have the democracy. We have lost a lot, but we’re still the country that most other countries look to for guidance and protection and that sort of thing.”

If America is still essentially intact, is it really such a problem that Trump is arguably a terrible manager? Bloomberg maintains that Trump has been lucky that none of his errors has been truly disastrous so far. “Just be thankful that some of the worst things that could have happened didn’t,” he says, pointing to the assassination of Iranian general Qasem Suleimani, which could have sparked a broader conflagration in the Middle East.

Trump and his allies point to episodes like that to argue that he’s right to take bold actions that upset the establishment, and that in doing so he’s taking on the governing class’s endemic timidity. The economy didn’t crash when he was elected. A war didn’t break out when he moved the U.S. Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. NATO didn’t fall apart when Trump bad-mouthed it. Time and again, pointy-headed experts have warned of dire consequences from the president’s actions, only to have America muddle through more or less as before.

To Bloomberg, this is attributable to the virtues of the permanent government, which Trump derides as the “deep state.” “The bureaucracy is going to outlive us all, and they know they’re going to outlive us all,” he says. “So if there is something that the president does which is cuckoo, that’s our insurance policy.”

Perhaps, even in a freaked-out Democratic Party, there’s a latent longing for this sort of equanimity. The crowds at Bloomberg’s events, and his initial surge in the polls, suggest that there is at least some appetite for what he’s selling. His flop as a debater deflated the bubble somewhat. Onstage in Las Vegas and Charleston, he struggled to rebut predictable attacks on his history of insensitivity to women, his company’s secret settlements in gender-discrimination lawsuits and his administration’s “stop and frisk” policing practices. Many attendees at his events tell me the debates made them reconsider supporting him. Nevertheless, he still stands in third place in the national polling average with a healthy 15%.

Biden’s resounding South Carolina win and the withdrawal of Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg have led many Democrats to call for Bloomberg to drop out so the party’s moderates can rally around the former vice president. But Bloomberg says he plans to stay in the race until it produces a clear winner—or not. “If you look at the debate stage, I’m the only one that’s ever done anything,” he tells me. “Joe Biden was a legislator, and Sanders, Warren, and Amy. They don’t have any managerial experience whatsoever, and this is not a job where you can come in and get on training wheels.”

The morning after his first disastrous debate performance, Bloomberg appeared in Salt Lake City. Seeming not at all rattled, he gave his usual speech largely unaltered, talking about uniting the country and getting things done with “common sense plans that are achievable.” He deviated from the usual routine only to proclaim, “Look, the real winner of the debate last night was Donald Trump. Because I worry that we may very well be on the way to nominating someone who cannot win in November.” This imperturbability in the face of a potential campaign-ending calamity seemed discordant, until I realized it was exactly the point. If Bloomberg is the candidate you want in a crisis, it’s precisely because he’s so unruffled. He keeps his head when everyone else is losing theirs.

Midway through the Utah speech, a young woman in wide-legged jeans started shouting. “Mike Bloomberg was in Jeffrey Epstein’s little black book!” she yells. “Mike Bloomberg is evil!” As the crowd turns on her, she makes for the exit, crying, “InfoWars dot com!”

It was a reminder that you can try all you want, as Bloomberg has, to run a massive campaign that renders the candidate’s personal qualities all but irrelevant. But no matter how much money you have, you can never completely shut out the conspiracy and chaos of America in 2020.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Molly Ball/Houston at molly.ball@time.com