Pete Buttigieg was only half joking on the eve of the South Carolina primary when he wondered aloud to a crowd if it wasn’t “too late” to make another hire to help his struggling campaign. His aides sitting in the back of an American Legion hall in Sumter, S.C., audibly groaned, and one threw up his hands in open frustration.

No campaign staffer wants their boss to admit defeat in a contest before the polls even open, particularly if the campaign is in a precarious position. Though the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, had a strong early start as a presidential contender in the predominantly white states of Iowa and New Hampshire, he has failed to garner support among black voters.

And so Saturday’s contest in South Carolina, where roughly two-thirds of the Democratic electorate is African American, is not expected to be a good day for Buttigieg. Only 6% of black voters in the state’s Democratic primary support him, according to the last Emerson College poll. Looking ahead to the 14 states that will vote in three days on Super Tuesday, his odds aren’t much better as the electorate grows even more diverse.

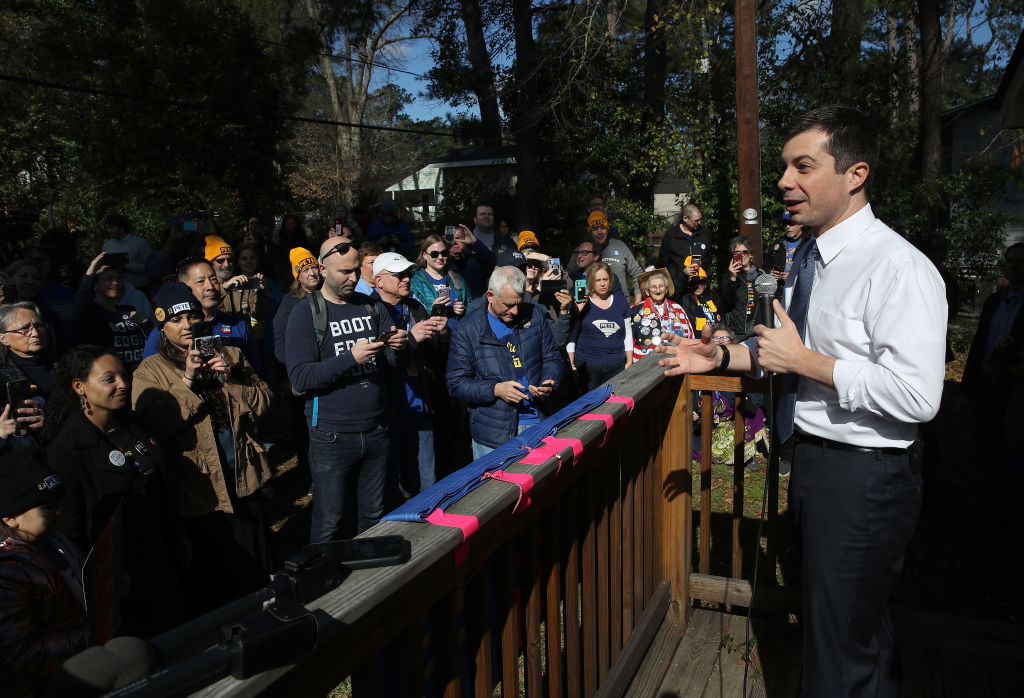

That mood of impending defeat imbued Buttigieg’s performance on stage on Friday in Sumter, a military town that is fighting lead in its drinking water like Flint. It was a potentially uncomfortable setting for Buttigieg, a gay veteran in a state where sexual orientation and gender identity are legal causes for dismissal. The invite-only crowd was friendly enough, but Buttigieg appeared exhausted. It was not the same candidate on stage who electrified hotel ballrooms on the way to victory in Iowa.

“I’m actually surprised he is still in the race,” says Ken Knops, a 66-year-old retiree who supported Andrew Yang until he dropped out. Now Knops is shopping around, including a skeptical visit to Buttigieg’s event. “I don’t know what [states] he wins on Super Tuesday.”

As Democratic presidential candidates head into the crucial Super Tuesday contest, the wide field of contenders is becoming a bigger and bigger problem. Bernie Sanders remains the frontrunner after the first three contests, and former Vice President Joe Biden is expected to do well in South Carolina and could potentially head into Super Tuesday with the second-largest bucket of delegates.

But no one else is ready to quit. Like Buttigieg, Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar are vowing to fight onward as the contests hit their backyards, and billionaire Mike Bloomberg is set to join the balloting this week. The wide field of moderates is divvying up the majority of votes not going to Sanders, paving the way for the Vermont Senator’s continued ascension in the race. If things continue at this pace, no one will secure the nomination before Democrats arrive in Milwaukee for their convention, meaning anything can happen.

Campaigning in South Carolina has not gone smoothly for Buttigieg. On Friday, his campaign abruptly canceled an event with small-town, African American mayors at a soul food restaurant in Fairfax, S.C., because so few of them were willing to attend. Rep. James Clyburn — a kingmaker in the state — threw his support behind Biden, effectively icing out any opening for the former mayor.

Hours later, Buttigieg stumbled when he was asked about his faith.

“Evangelists have historically voted Republican in thinking that’s where their morality lies. What are you doing to engage Christians across the country — especially white Christians — who normally will vote Republican against the concepts of compassion, against the concepts of humanity,” self-identified poet laureate of the Vote Common Good movement Genesis Be asked of Buttiegieg.

Buttigieg, who has been canceling events as he fights a nasty illness and isn’t campaigning as his best self, veered into an answer that was inarticulate at beset. “I love the idea that your movement has a poet laureate. Really exciting,” he said to applause. “I wonder if it’s too late to think up a way to have a poet laureate for our campaign. That’s a great idea.”

Still, Buttigieg has no plans to step aside, at least for now, as he heads on Sunday to Georgia with former President Jimmy Carter, then head to Texas, Oklahoma and Idaho in the coming days. Buttigieg plans to continue his campaign preaching compassion and civility, a vision that can be hard to compete with Sanders’ promise of a revolution.

He may be losing among black voters, but he remains committed to winning over the slice of the electorate he describes as “future former Republicans” like Marc Warren, a 49-year-old architect from Columbia, S.C., who joined Buttigieg’s primary-eve rally in the state’s capital city. A Republican who dislikes Trump, Warren says he plans to vote for Buttigieg even though he has zero expectations he can win. “He has a really big hill to climb, but we can’t sit on our hands because it will be tough,” he says.

Other supporters who came out to support Buttigieg in South Carolina said they were hoping that once the wide field of moderates narrowed, Buttigieg would have a better chance of staying in the game.

“It’s time for some people to get out. It’s time to consolidate,” says Caroline Keene, a 46-year-old teacher from Camden, S.C., who planned on voting for Buttigieg the next day. “It’s time for us to pick one person who isn’t Bernie and rally behind that person.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Philip Elliott / Sumter, S.C. at philip.elliott@time.com