Agnieszka Kurant’s lower Manhattan studio stands among a scattering of cultural outposts that represent some of the most recent efforts of the avant guard to grapple with our cultural moment. When I visited in late January, a gallery two doors down was hosting a reproductive rights-themed show with works listed for upwards of $30,000. Across the street, four floors of the windowless New Museum were taken over by a retrospective of artist Hans Haacke, which included a demographic survey, a portrait of Ronald Reagan and a grass-covered mound of dirt. The seventh floor was occupied by a “mixed reality pop-up,” sponsored by Ruinart champagne, in which visitors could wander about in augmented reality glasses. Minders politely asked those without reservations to “step away from the experience.”

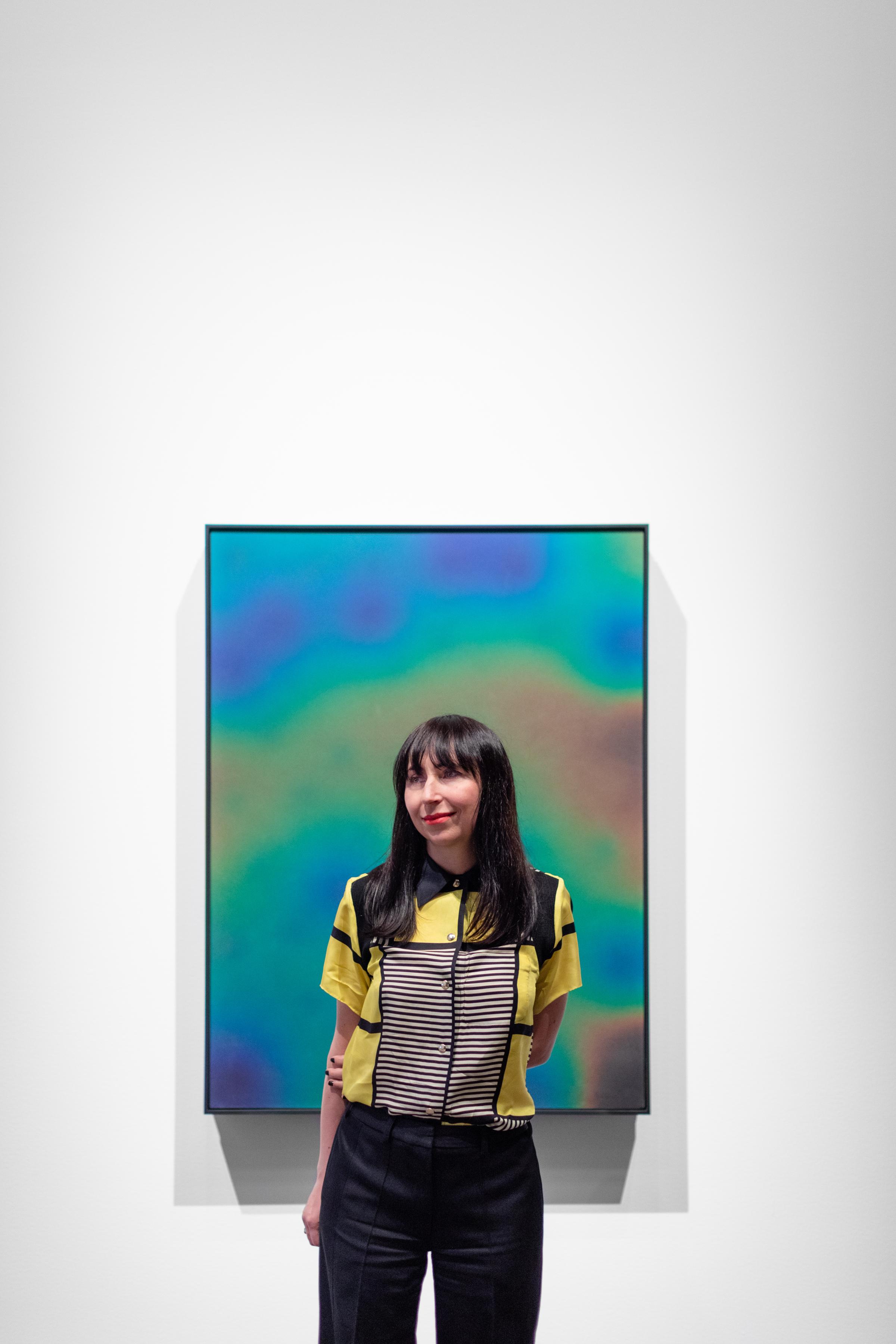

Technology and late capitalism similarly intersect in Kurant’s work, though perhaps with a greater degree of self-awareness. A conceptual artist, she explores modern questions over data rights, online labor exploitation and the power of big corporations. With growing public awareness of issues like the commodification of “big data” and the ever-increasing power of artificial intelligence (AI), she’s part of a new generation of artists and curators who are trying to represent the nature of these new technologies, and the ways we are being transformed by them.

“To talk about any kind of new media or new technology, sometimes it’s better to use an analogue technology,” Kurant says, showing a photograph of a 2017 piece entitled “A.A.I.” She says the name is based on a phrase coined by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, “artificial artificial intelligence,” which describes the process of digitally outsourcing work to human freelancers through distributed labor platforms like Amazon Mechanical Turk. The artwork consists of a series of fluorescent termite mounds created from green, blue, violet, yellow or orange artificial sand. She collaborated with entomologists at the University of Florida to enlist the labor of the termites.

“If you give them something else that is not sand … they will not notice the difference and they will still keep building,” Kurant says. She sees termite societies as a kind of “dispersed factory” akin to the mechanism by which large tech companies collect massive quantities of information about users in order to power sophisticated advertising algorithms. “We are all working on a very long, gigantic conveyor belt providing our data or expressing our emotions so that corporations could capitalize on it,” she says.

New digitally-enabled economic systems figure even more directly into some of Kurant’s other pieces. In her “Production Line” series, produced between 2016 and 2017, she and co-author John Menick contracted hundreds of Amazon Mechanical Turk workers to each draw a single line which were then algorithmically assembled into cohesive drawings. When a painting is sold, the “Turkers” are given part of the profits.

Collectivity figures prominently in another of Kurant’s series, “The End of Signature,” in which she used computer algorithms to coalesce hundreds of individual signatures into a single illegible line. Another of her series, “Conversions” (2019), focuses on the ways in which collective “social energy,” in the form of tweets, posts and online searches, is transformed into revenue streams. Consisting of a copper plate covered with liquid crystal paint and attached to computer-controlled heat pumps, the “painting” changes composition in response to algorithmic sentiment analysis of tens of thousands of social media feeds tied to protest movements, continuously transforming collective societal disquiet into physical heat energy.

“Even the activities of protest movements are somehow taken advantage of by corporations,” says Kurant, explaining the context of the piece. “There is a price tag on social energies.”

Other contemporary artists are also grappling with the intersection of artificial intelligence, data and capitalism. At San Francisco’s de Young museum, an exhibition entitled “Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI” (Feb. 22 – Oct. 25, 2020) takes its name from a term describing how artificial representations of ourselves can come too close for comfort. According to curator Claudia Schmuckli, the installation makes the case that widespread use of AI has brought about a fundamental change in humans’ relationship with machines.

“The contemporary uncanny valley is no longer occupied by the image of the machine … but by the statistical data profiles of humans that are compiled by algorithms, which are designed to mine and analyze behavior and project them into tradable or governable futures,” Schmuckli says. She adds that famous pop culture representations of AI, like 2001’s HAL and Schwarzenegger’s Terminator, have been replaced by something even more unsettling: the reflected data profiles generated from our own lives.

Notions of uncanny resemblance figure prominently into another piece at the de Young, “Conversations with Bina48,” which features artist Stephanie Dinkins speaking with a humanoid social robot built to resemble a black woman.

“[I] wanted to see what would happen if I tried to become friends,” Dinkins tells TIME. She’s interested in exploring how communities of color fit into the “new world” being created by companies struggling to become more diverse. “There is a small subsection of the population … that’s creating AI ecosystems that will be contributing to many of our lives,” she says. “What happens if regular people are not a part of thinking about and calling for transparency?”

Other artists are using AI to take decidedly unconventional approaches to the uncertainties of our time. In “BOB (Bag of Beliefs)” (2018-2019), artist Ian Cheng combines neural networks with a video game engine to create an intelligent simulation named BOB. The digital animal resembles a multi-headed snake. As users interact with it via a smartphone app, BOB develops “beliefs” about the world it inhabits, and its personality evolves over the course of a simulated lifetime. “BOB’s body and BOB’s personality and BOB’s beliefs continue to grow,” explains Cheng. “BOB is quite particular by the end of any of these given exhibitions.”

New technologies get blamed for much of today’s collective unease, but for Cheng, that same technology may also provide one of the best ways to come to terms with the times we live in. “I want to feel that the thing I’m looking at is alive, that it has something that can surprise me,” Cheng says of his artificially intelligent artworks. “It mirrors a bit the way that life feels right now where everything is constantly changing — there’s no story that stays stable for too long.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Alejandro de la Garza at alejandro.delagarza@time.com