I don’t recall who first told me that I wasn’t a victim, but it happened soon after someone told me I was raped.

I was 17 and wasted. I was a nerd who had been drunk maybe three times in my life, surrounded by the safety of giggling girlfriends and a childhood home free of vacationing parents. I had never been to an actual party where everyone was drinking, and a boy seemed to like me, and I had no curfew or responsible adults to report to. I was a virgin who didn’t want to be one much longer.

Several strains of the impossible became possible all at once. There was nothing but the present moment, walking out of a party that was too loud and too crowded, holding a guy’s hand, like I was the kind of girl who got to do that.

Well, what did you expect to happen?

I knew this: a man I had some vague sexual interest in, mostly because he showed interest in me, had brought me drinks all night, and then I left a party with him. I knew this: I kissed him outside that party, on purpose, standing between two white, green-shuttered colonial-style dorms, the thumping heartbeat of De La Soul or Deee-Lite pouring out open windows.

And I knew this: whatever I expected when I left a party with a guy whose name I had not committed to memory, I did not expect to end up on damp, patchy grass, floppily trying to convince him to stop f*cking me. I did not expect to stumble toward three identical white dormitories, crying and hoping I was right about which one was mine. I did not expect my roommate to react to the very sight of me with shock, or insist that I tell our RA in the morning. I did not expect to end up at the hospital, where a very kind man examined my genitals, prescribed the morning-after pill, gently scolded me for smoking, asked if I wanted the police to do a rape kit—I declined, not wanting my parents to know anything about it—and told me to do follow-up STD testing with a campus doctor in six months. I did not expect to see my rapist in the dining hall a day or two later and suddenly understand how tiny our 500-student campus was. I did not expect the campus doctor who did the follow-up testing, another strange man penetrating me, to treat me with naked contempt for having unprotected sex during the window when there was no longer any excuse for ignorance about HIV but the good drugs hadn’t arrived yet. I did not expect to become a feminist. I did not expect to write a book about rape culture. I did not expect to write this essay more than 25 years later.

After the rape, I didn’t blame myself. It was 1992, and feminism had gotten through to me enough that when I said something like, “I just had sex on the lawn with a guy I don’t know he wouldn’t stop” and heard “That’s called rape” in response, I thought, Yes, I suppose it is.

This made it weird when well-meaning people—my RA, an ER doctor, a counselor—reminded me, again and again, that it wasn’t my fault. These people were beautiful, compassionate angels who only wanted to help, as long as helping meant giving the same canned speeches to every victim who came along. “It’s not your fault” is a Thing You Are Supposed to Say, a theoretically healing benediction, but I never felt the kind of shame that that reassurance is meant to ameliorate.

The angels told me with the same earnest vehemence that the preferred alternative to victim was survivor. I get the “survivor” thing, in theory. Rape is fundamentally a crime of power, and whether the mechanism is gunpoint or incapacitation by alcohol, the very essence of it is to remind the [victim] [survivor] [person being raped] [check all that apply] that they are not in control of what happens to their own body. Death is the ultimate loss of bodily control, and every lesser instance is on some level its harbinger. This is how rape becomes a weapon of war and the threat of it an element of women’s systemic oppression. All very Women’s Studies 101, thanks to Susan Brownmiller’s work in the 1970s.

By 1992, that theory had traveled as far as my RA’s training at my small liberal arts college in New England. Survivor was, she said, my word and identity to claim. However, in practice, I did not feel I had survived anything in particular. I felt that a strange guy had done things I didn’t want him to do to my body, and I understood that the simplest word for that was rape. But I had never doubted there would be an endpoint. I had endured a thing, but to say I survived it was no more meaningful than saying I’d survived every moment of my life until then. To call myself a “survivor” felt somewhere between putting on airs and appropriating a visceral pain that wasn’t mine.

This is the part where the angels would say, “Here’s some literature and let me remind you once more that it’s not your fault.” They’d say that violation is violation, that survivors often underplay their own experiences and deny the gravity of rape, usually as a means of self-protection.

Listen, I am a person who minimizes the gravity of everything as a means of self-protection. On the morning of my mother’s funeral, I came upon my sisters sobbing and hugging and, unable to tolerate the depth and earnestness of their despair, cut it short with a snarky, “God, who died?” To be fair to the angels, what they were describing sounds a lot like me.

But I don’t minimize the violation of my rape. I draw a sharp distinction between what a man did to me on the lawn outside a house party and a near-death experience, but let’s be clear: I became a mouthy public feminist largely because of that man doing things I didn’t want him to do to my body. I’m still telling the story almost two decades into a different century, a different millennium. The scarred and stiffened muscle of my heart would love to finish telling the story, believe me, but, having passed our silver anniversary, the story and I have grown so enmeshed, we’re probably going to die in the same bed.

But the question that first struck me at 17 and continues to haunt me at 43 is this: What’s wrong with being a victim?

What’s wrong with being a victim?

Obviously, becoming a victim is undesirable. We don’t wish for bad things beyond our control to come along and interfere with our plans. But once the bad thing has happened, why are we so allergic to using the simplest, most accurate language to describe the condition of being post–bad thing?

I had been violated without being in fear for my life, ergo I was far more accurately termed a “victim” than a “survivor.” That part was simple enough. The complicated part was that many other people who had been raped preferred survivor and found victim actively insulting.

Once the bad thing has happened, why are we so allergic to using the simplest, most accurate language to describe the condition of being post–bad thing?

It wasn’t clear to me why the plain truth should be insulting, based on my understanding of victim as “a person to whom something bad has happened, through no fault of their own.” The original meaning of victim, from the Latin victima, referred specifically to religious sacrifices. Something lived and then, at the hands of believers in a morbidly greedy god or gods, it died. A small animal, a child, a virgin, Jesus Christ.

In the 17th century, we begin to see it used metaphorically, for, as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it, “one who suffers severely in body or property through cruel or oppressive treatment.” Scrolling down through the layers of nuance, we find a definition that includes a judgment of how seriously we should take it: “In weaker sense: One who suffers some injury, hardship, or loss, is badly treated or taken advantage of, etc.”

But pick up a thesaurus, or type “victim” into an online one, and you begin to get the picture: butt, clown, dupe, fool, gopher, gudgeon, gull, mark, patsy, pawn, pigeon, prey, pushover, stooge, sucker. These are the words that begin rewriting your story as soon as you utter the word victim. These are the synonyms and judgments that cling like burrs to your helpless body. Well, what did you expect to happen?

In 2015, Susan Brownmiller herself gave an interview to New York magazine in which she called the campus-based anti-rape movement “a very limited movement that doesn’t accept reality,” adding: “Culture may tell you, ‘You can drink as much as men,’ but you can’t. People think they can have it all ways. The slut marches bothered me, too, when they said you can wear whatever you want. Well sure, but you look like a hooker. They say, ‘That doesn’t matter,’ but it matters to the man who wants to rape. It’s unrealistic. I don’t know what happened to the understanding people had in the 1970s.”

Never mind that it’s just as illegal and immoral to rape sex workers as young editorial assistants or retail clerks or ice cream scoopers who wish to express their sexuality without being assaulted. To a great many people, apparently including the mother of the anti-rape movement, victims are people who weren’t smart enough to avoid becoming victims.

What’s wrong with being a victim?

Another strain of anti-victim sentiment seems based on the premise that there is something intrinsically appealing about becoming a victim. Like people who hear victim and think patsy, pawn, pigeon, those who complain about “victimhood culture” don’t accept the “through no fault of their own” part.

Consider the anti-feminist usage of phrases such as “playing the victim” and “professional victim.” Consider that “Refuse to Be a Victim” is the name of a National Rifle Association training program for women. Consider that if one enters “victimhood” into the search bar of a large online bookseller that made victims of an entire industry, the top results are titles like these: The Rise of Victimhood Culture: Microaggressions, Safe Spaces, and the New Culture Wars; The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting up a Generation for Failure; The Great Blame Game Escape: Breaking Free from Victimhood and Claiming Your Independence with Personal Responsibility.

No, wait, it’s worse than that. In an article titled “The Rape Epidemic Is a Fiction,” right-wing pundit Kevin Williamson argues that anti-rape activists’ real goal is not preventing sexual violence but “making opposition to feminist political priorities a quasi-criminal offense and using the horrific crime of rape as a cultural and political cudgel.”

I don’t want to make too much of the violent metaphor, lest I be called to account for my own bloodthirsty rhetorical flourishes, but the image he’s created—victimhood as weapon—illustrates how some people come to regard victim status as a type of power, rather than its opposite. That’s what’s ostensibly appealing about it: the perceived ability to pull emotional rank over non-victims when discussing contentious cultural issues.

What’s wrong with being a victim?

Being a reasonably polite person who doesn’t like hurting people, I am happy to use the word survivor for those who prefer it.

But when you’re part of a group that prefers one word and you prefer another, politeness to others comes into conflict with your very identity—or at least with how you articulate it. And there are times—early in the process of reclamation, or soon after the introduction of a neologism—when members of a group face off over the acceptability of a word.

Is it my story to tell or not? Is this a thing that happened to me, or a thing that happens to one in six American women?

Whether I should call myself a “victim” or a “survivor” is a relatively simple question—I’m a grown woman who can call herself whatever she wants—that pops the lid on a much more difficult one: How precisely should I tell the truth about my own life, if increased precision edges us closer to damaging anti-woman stereotypes and bad-faith arguments stretching all the way back to Eve in the garden? At what point does my need to break everything down to its most literal, straightforward definition make me vulnerable to criticism that quietly indicts every other person who has been raped?

In other words, is it my story to tell or not? Is this a thing that happened to me, or a thing that happens to one in six American women? Even if I prefer not to be called a “survivor,” what do I owe to those already traumatized people who might be harmed by the implication that they, too, are “victims”?

Thinking seriously about pejorative language as a tool of oppression, a mechanism by which we reinforce cultural disdain for entire groups of people, begets frequent internal conflicts of this nature. Do I, as a woman, have a right to call other women “bitches” if I can make a cogent argument that it should rightly be a term of endearment? As someone who suffers from depression, am I allowed to roll my eyes at disability activists who discourage the colloquial use of crazy and insane? Is a mood disorder technically the same as a mental illness? Was that year I spent lying on my side in front of the TV a disorder, a disability, an unfortunate choice? What about the period while I was writing my book on rape culture, when my husband sat me down and said, “I will write a check to return the advance right now, if you’ll stop doing this to yourself”?

What’s wrong with being a victim?

What’s wrong is that using the word makes you a palimpsest on which people will write whatever they happen to think it means. Ultimately, I suspect this is what people who identify as survivors (or something else entirely) are getting at when they refuse the label “victim.” It is not merely that they don’t wish to be seen by aging feminists and other purveyors of smug “common sense” as pushovers, stooges or suckers. Or that they don’t wish to be accused of exploiting some (always hypothetical) innocent victim’s genuine pain to garner sympathy for what should rightly be their own shame. Or that they don’t wish to hurt other [your word of choice]s. It’s not even that they don’t wish to be seen as weak, or broken or permanently traumatized. It’s that they want to speak for themselves. They want their stories to be theirs.

Speaking only for myself, if such a thing is possible, I’m just trying to tell you what is true.

It is true that one cannot desire or invite an act defined by non-consent.

It is true that I borrowed a tight, black dress; that I loved the way alcohol helped me slide out of my inhibitions like a used-up skin; that I wanted the raw new me underneath to touch and be touched, up to a certain point.

It is true that only rapists deserve the blame for rape; that clothing choices, drinking and kissing do not indicate consent to sex; that rape and sex are distant cousins, not twins; that predators often use alcohol to control their victims.

It is true that 17 is so goddamned young.

It is true that I went on to become a happy and settled adult. Mostly.

It is true that I have been spiraling around the same story for 25 years.

And it is true that any attempt to sort human beings into categories necessarily shaves off some of our humanity, replacing each unique individual with a type. Would you rather be the victim type, who courts and marinates in adversity, or the survivor type, who triumphs over it? Are you pawn, pigeon, prey or a strong, capable woman who courageously saved her own life? There’s no option for “Would prefer not to confront adversity, as a rule, but it’s not always up to me.”

In truth, I am both and I am neither. I am one human being with a particular story about a life-shaping act of violence that, no matter how many times I tell it, only I will ever know by heart. Call me whatever you like.

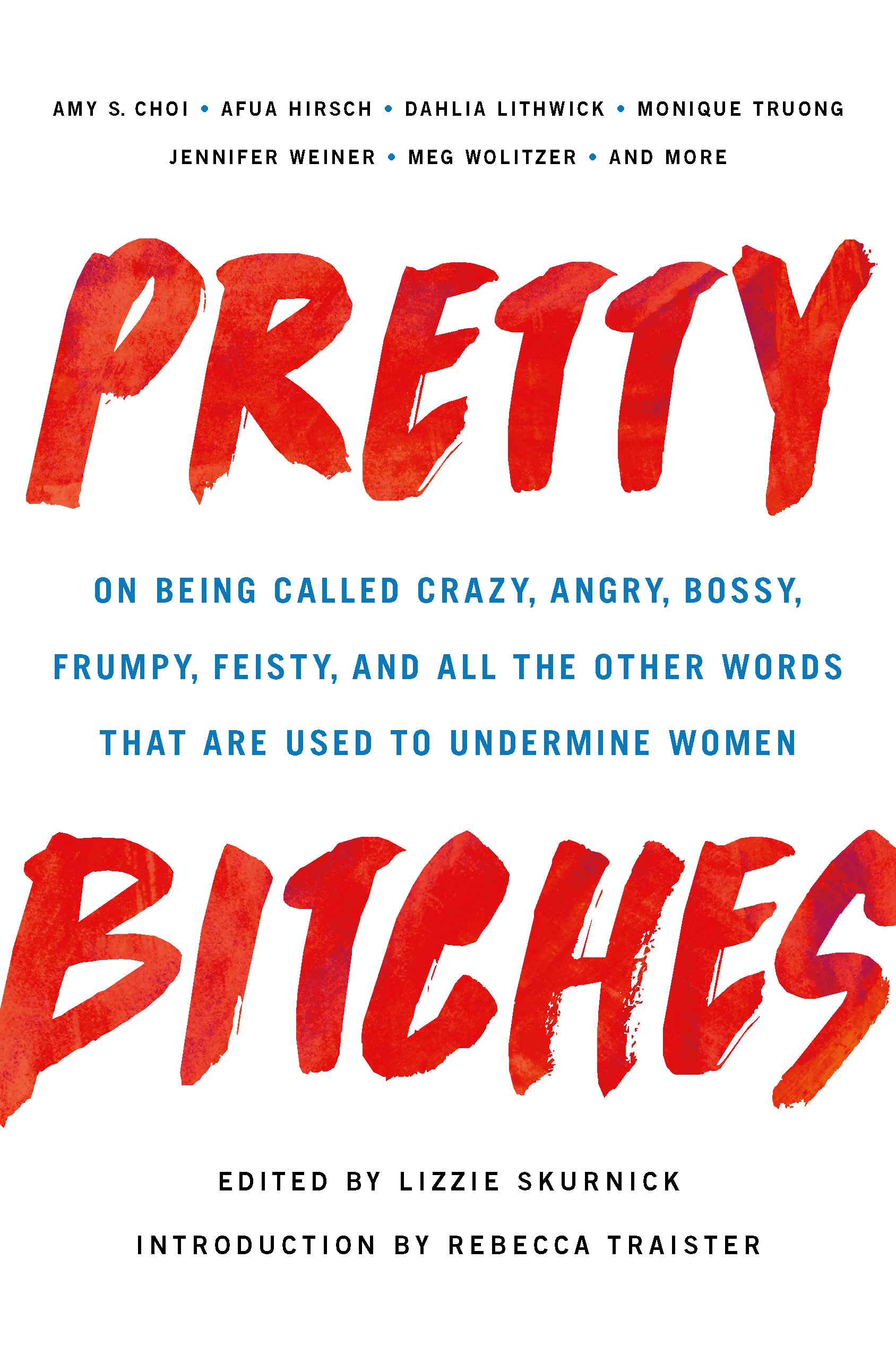

Excerpted from Pretty Bitches by Lizzie Skurnick. Copyright © 2020 by Lizzie Skurnick. Reprinted by permission of Seal Press, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com