On a September day in 1969, in the projects of Brooklyn, a drunken deacon named Sportcoat shoots the local drug dealer, Deems. The community–an ensemble of black, Puerto Rican, Italian and Irish characters, reflecting the diversity that has always made New York City distinct–reacts to the shooting with a combination of gossip, embellishment of details and reflection on what it means for their home. But Sportcoat’s actions also set into motion an underground network of mobsters and malcontents, along with cops and church folk, all trying to get to the bottom of how a washed-up deacon came to shoot a young man he once coached in baseball.

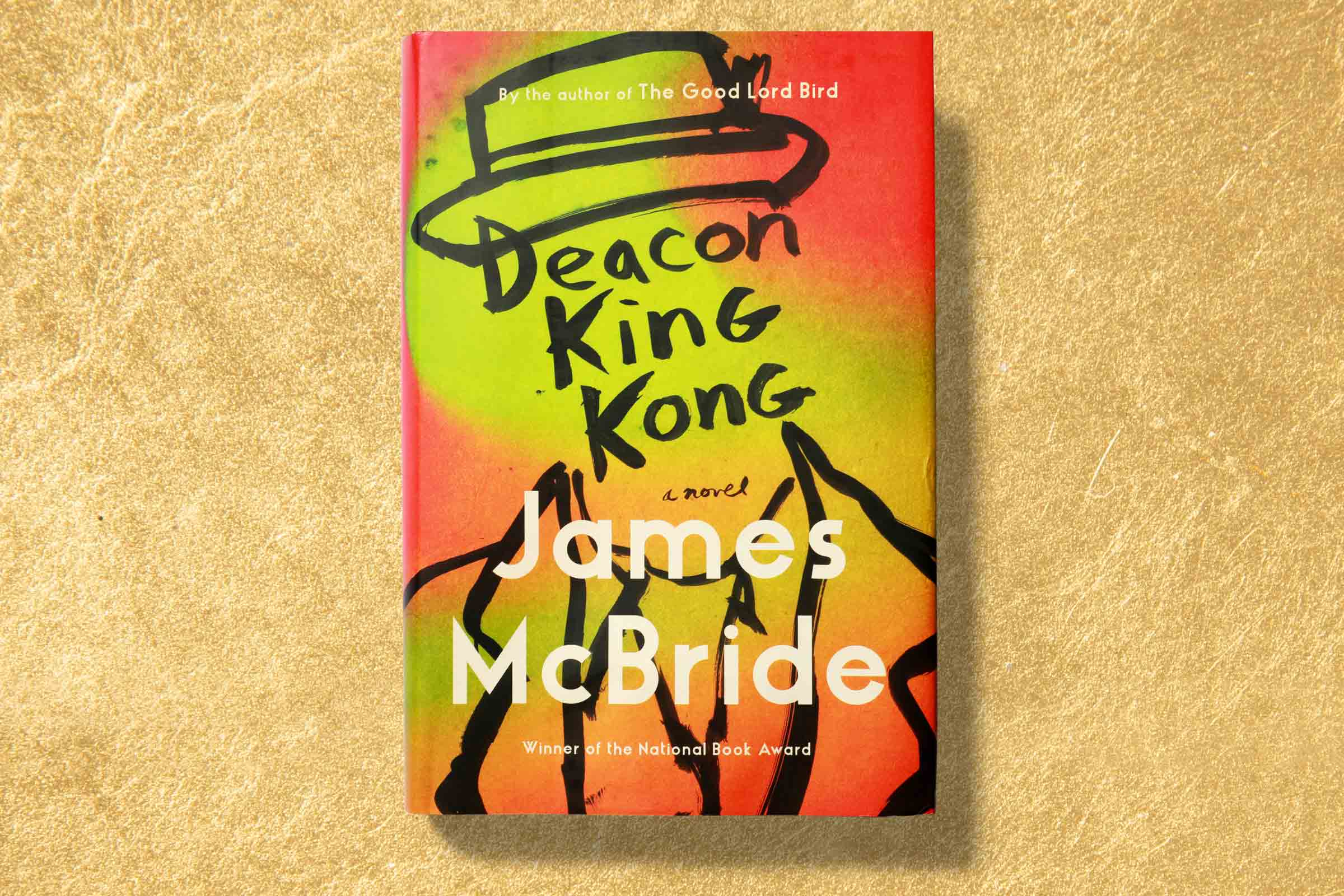

On its surface, Deacon King Kong is about the tension between wayward souls and those on the straight and narrow. But on a deeper level, James McBride’s first novel since his National Book Award–winning The Good Lord Bird is about our deep and complex relationships to the places and people who make us who we are, and how we change–either in spite or because of them. The tie that binds everyone in these pages is how they strive for a life that is safe and steeped in love. Many find that in their faith; a few manage to find it in one another.

Readers of The Good Lord Bird will recognize shades of McBride’s hilarious dialogue and an attention to detail that reveal a complex local history. Capturing humanity through satire and witticisms, McBride draws everyday heroes: bickering church ladies collecting coins for the Christmas Club box; mothers washing the soiled clothes of other people’s children; weathered gangsters sending quality cheese to the projects.

McBride positions Deacon King Kong on the precipice of a profound historical moment: as he illustrates, these knit-together old neighborhoods fell away after broader societal and urban shifts, not just in New York but around the country, beginning in the 1970s after the deaths of civil rights leaders and changemakers. In the new world, there would be nothing so uniting as a town drunk and his love and loathing for the promising ballplayer who turns to drugs. McBride’s novel is a rich and vivid multicultural history. But he also depicts the vulnerability of men who show most of the world only their gruff exteriors, rendered with rare and memorable tenderness.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com