For a woman to embark on a walking expedition is to do more than simply place one foot ahead of another. When women tie up their laces and head out into the wilderness, they reclaim terrains that for centuries, have been deemed unsafe and unfit for women.

Historically, men have had the opportunity to explore the earth’s many wild places while women have been constrained to the home. The idea that rugged geographies can only be conquered and tamed by men persists today. On top of this, to undertake a solo journey while female is to take on risk; it is to brave a space that has claimed the lives of others who have tried.

And yet, the history of exploration is also women’s history.

For decades, women around the world have traversed solo through rocky rivers and dusty deserts, looking beyond the prejudice and risks that face them. From carving out their own routes to taking on trails reserved for men, these 7 women are just a few of those who have helped reclaim women’s place in nature, one step at a time.

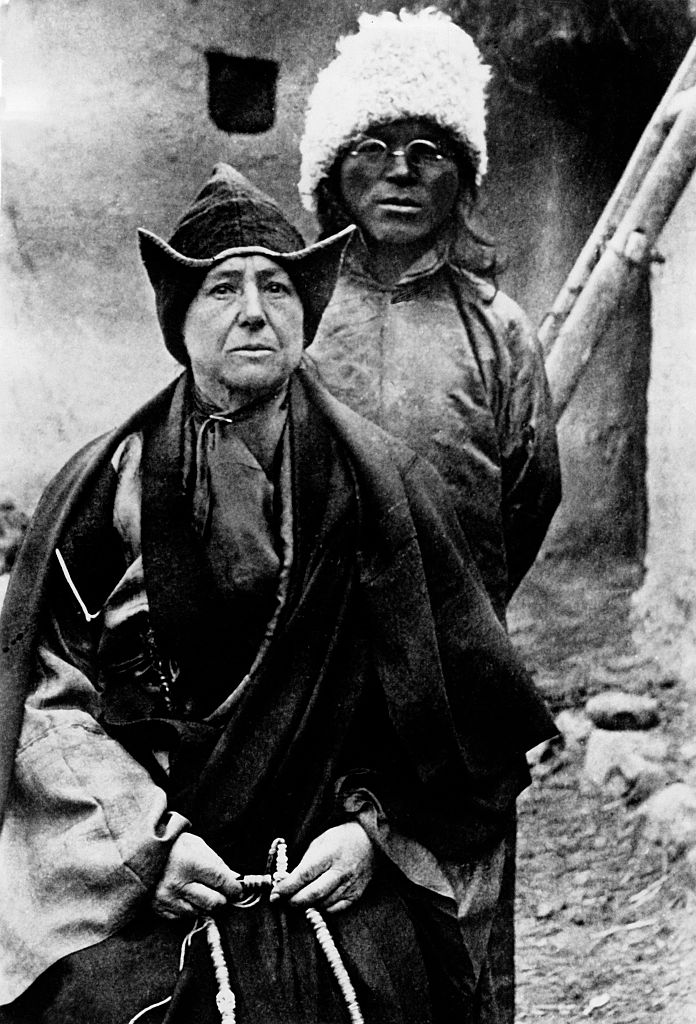

Alexandra David-Néel

“Ever since I was five years old, a tiny precocious child of Paris, I wished to move out of the narrow limits in which, like all children of my age, I was then kept,” Alexandra David-Néel wrote in the preface of her book, My Journey To Lhasa. “I craved to go beyond the garden gate, to follow the road that passed it by, and to set out for the Unknown.”

David-Néel went far beyond her garden gate. From Tibet to India, David-Néel spent the majority of her life exploring Southern Asia. A Belgian-French explorer, David-Néel became one of the most celebrated Western Buddhist pioneers and was the first foreign woman to explore Tibet. In 1924, David-Néel disguised herself as a beggar and made her way to the holy city of Lhasa, which at the time, was forbidden to foreigners. Born in 1868, David-Néel’s adventurous spirit was unheard of for a woman. But for David-Néel, exploration was a pathway for emancipation.

In a feminist text published in 1909, David-Néel wrote, “if we have a firm will to emancipate ourselves from the legal bind in which we are held by men, it will be advisable, first, to think of emancipating ourselves from the intimate bind under which we place ourselves.”

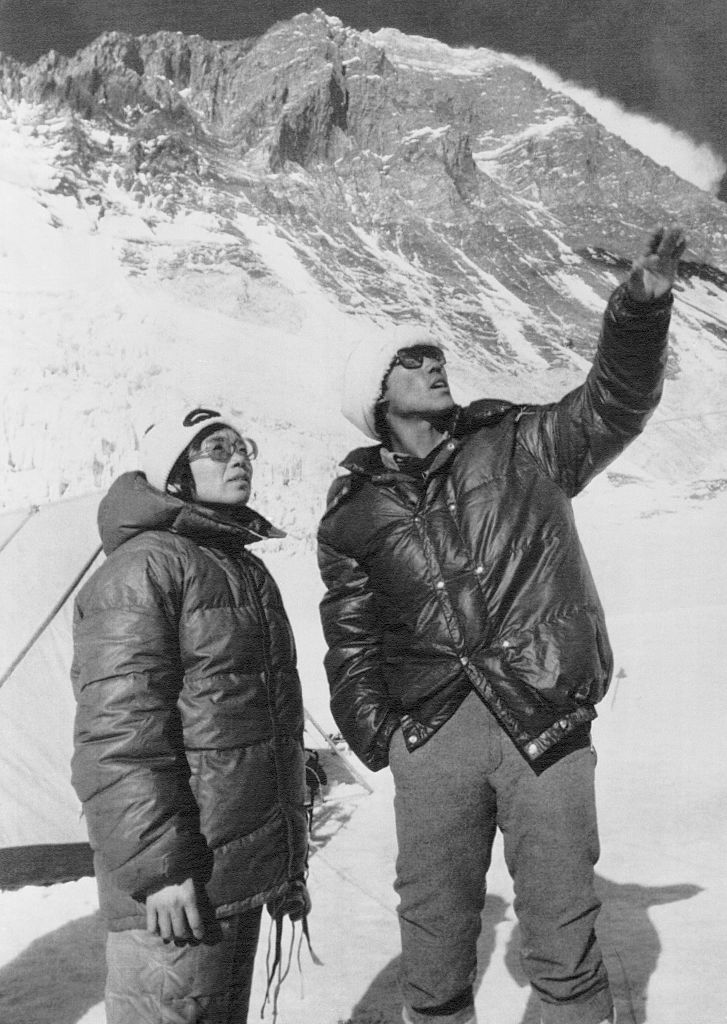

Junko Tabei

“I can’t understand why men make all this fuss about Everest,” Junko Tabei, the first woman to have summited mount Everest once said of the world’s highest peak. “It’s only a mountain.”

Tabei was a pioneering Japanese mountaineer, who reached Everest in 1975 despite her camp being buried by an avalanche. At only 4-ft.-9-in. tall, Tabei shattered stereotypes about what mountaineers were supposed to look like. She climbed the tallest mountains in more than 70 countries and became the first woman to reach the “seven summits,” the highest peaks on all continents.

“Most Japanese men of my generation would expect the woman to stay at home and clean the house,” she once said in an interview.

Tabei, who died in 2016, encouraged other women to become mountaineers, and founded the first women’s climbing club in Japan in 1969 during a time when most climbing clubs banned women. In Honouring High Places, a memoir that celebrates Tabei’s life, her friend Setsuko Kitamura writes that Tabei “continued opening the door to nature for all.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Robyn Davidson

In 1977, 26 year-old Robyn Davidson embarked on a 1700-mile journey through the Western Australian desert, with three camels and a dog named Diggity. Starting in Alice Springs, Davidson journeyed through parts of the Australian outback unknown to most, ultimately walking her way to the Indian Ocean.

In her memoir, Tracks, Davidson speaks of the liberation she found alone in the desert, where she was free of “prettiness and attractiveness.” She describes walking naked under the blazing Australian sun, as menstrual blood drips down her leg. “I hope that I will always see the obsession with social graces and female modesty for the perverted crippling insanity it really is,” she writes. Her reflections were in part sparked by her encounters with Australia’s aboriginal communities, where, Davidson notes, women had more power before colonization changed the cultural fabric of these societies.

For Davidson, her journey through the desert taught her that “you are as powerful and strong as you allow yourself to be” and that to the project of freedom is “one of the few that count.”

Karen Darke

“I always thought I’d rather be dead than paralysed,” Karen Darke, a British explorer and Paralympian writes in her memoir, If you Fall. “One slip, one moment and everything changes.”

Within her first two decades of life, Darke had already carved out her place in the mountaineering world. In 1991, she climbed Mont Blanc and Matterhorn. The following year, she won the Swiss KIMM Mountain marathon.

But in 1993, Darke fell off a cliff, becoming paralyzed from the chest down. This injury, however, did not stop Darke from exploring the world’s wild places. Since her accident, Darke has handbiked her way through the Himalayas and the Chilean Patagonia, traversed the length of Japan, kayaked the inside passage from Vancouver to Juneau, Alaska, sit-skied across the Greenland icecap, circumnavigated Corsica by sea kayak, climbed El Capitan in Yosemite, and traveled from Canada to Mexico on the Pacific Coastal Trail. Darke was also a silver medalist in the London 2012 Paralympics and became a Paralympic Champion in the Rio 2016 games.

Through her explorations of land, sea and ice, Darke has shown that women of all ability levels belong in the outdoors. As she notes, “ability is a state of mind, not a state of body.”

Thinlas Chorol

Born in a Takmachik, a high-altitude village in the Indian Himalayas, Thinlas Chorol grew up traversing the dry, rocky terrain that surrounded her. During the holidays of her childhood, Chorol would trek through the mountains with her father to care for their herds. Chorol’s region, Ladakh, opened up for tourism in 1974, but it was men who reaped the benefits of this new industry, becoming trekking guides for wealthy foreigners. “They told me that local culture wouldn’t accept a woman going to the mountains with tourists,” Chorol has written.

Chorol, who was the first in her village to attend school, noticed a gap in this tourism market. Female travelers felt safer trekking with female guides and Ladakhi women—who had been systematically pushed out of the tourism economy—were looking for employment. In 2009, Chorol founded the Ladakhi Women’s Travel Company, the first female owned and operated trekking company in the Himalayas.

But carving out a place for women in the trekking industry is just one of Chorol’s many projects. She also co-founded Ladakhi Women’s Welfare Network after a woman was gang raped in a nearby area.

“I have learned that if a woman has the courage to do something in a male world, it will be hard work,” Chorol writes. “But success will be hers in time.”

Sarah Marquis

In 2010, Swiss explorer Sarah Marquis embarked on a 12,427 mile solo journey by foot from Siberia to Australia, crossing six countries over the course of three years.

On her journey, Marquis encountered wildly different ecosystems, from freezing fields to humid jungles. She also encountered sexism: Marquis disguised herself as a man in regions where being a woman was particularly unsafe. “There were so many nights when I fell asleep with danger prowling nearby,” she has written. A year after Marquis was named National Geographic‘s Adventurer of the Year in 2014, she embarked on a “surviving expedition” and was dropped by helicopter into the Australian outback, emerging three months later.

Marquis dedicated her memoir, Wild By Nature, “to all the women throughout the world who are still fighting for their freedom and to those who have gained it, but don’t use it.” She adds, “put on your shoes. We’re going walking.”

Rahawa Haile

“As a queer black woman, I’m among the last people anyone expects to see on a through-hike,” Rahawa Haile, an Eritrean-American has written. “But nature is a place I’ve always belonged.”

In the United States, the history of segregation — when many beaches and trails were reserved for whites only — can help inhibit many people of color from engaging with the great outdoors. Haile is challenging that through her steps and her words. Haile walked the Appalachian trail in 2016 and wrote about how her perspective as a queer black woman affected her experience.

After Jeff Sessions became Attorney General in 2017, Haile decided to follow the footsteps of civil rights marchers and walk from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. For Haile, the walk was about “reclaiming enough of an illusion of safety to survive the next four years in this country.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com