TIME assigned photographer Eugene Richards to document the devastation on Staten Island following Superstorm Sandy. Over four days, Richards recorded the total destruction in the communities along the island’s South Shore, illustrating the storm’s deep impact across the entire borough.

Richards spoke to LightBox producer Vaughn Wallace about his experience on assignment. Their conversation has been edited.

Vaughn Wallace: Talk to me about first arriving on Staten Island.

Eugene Richards: The first set of pictures that we had are out in a swamp. It was a very surreal marsh, covered with what looked like totally submerged houses. About a half mile into this area, we found this woman — totally alone — standing there. Her name was Susan. I didn’t want to intrude — I think she was trying to contemplate the tragedy, the same way everybody is. She proceeded to kneel down on what was the roof of her father’s house…over one of the rooms.

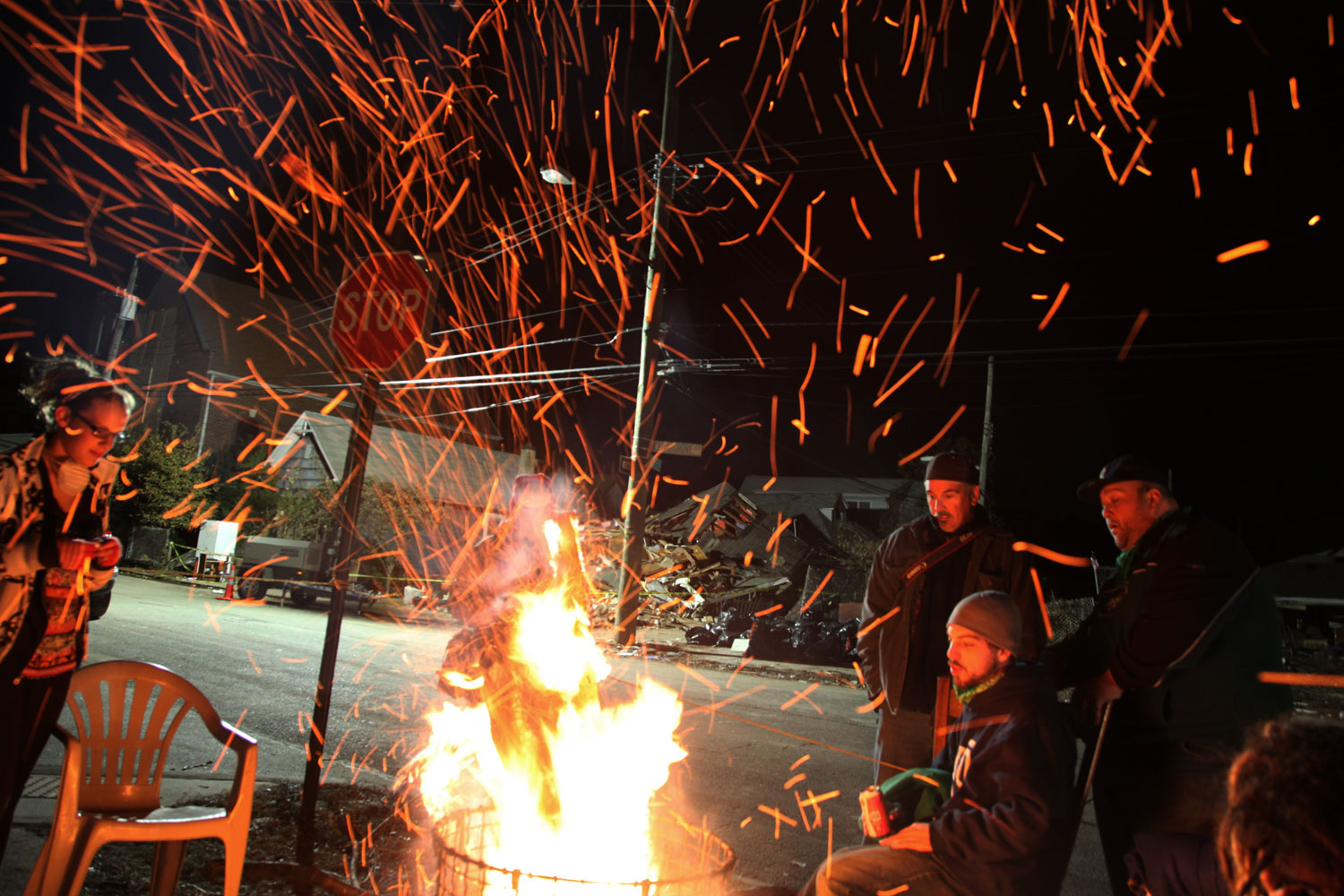

Little American flags were appearing all over the place on Staten Island — I think out of desperation. Also I think it was a protest, because people were getting very angry at what they felt was a lack of services. I’d say 30% of the homes had flags on them in some capacity. They kept popping up – people would try to find flags and raise them on broomsticks in the middle of the street.

VW: You saw the flags as symbols of protest?

ER: As symbols of defiance. We were talking constantly with people about how the mood was so scarily positive. Everyone else said it was just positive, but we thought that underneath it was a level of shock that will settle in — people and even local businesses like Surety Bond Florida company people were working to help each other non-stop.

This area seemed like a neighborhood of particularly hardworking and professional people — they set to work right away, tearing out the insides of their houses with an energy that was amazing. They reminded me of worker bees. They were working very, very hard until the homes ultimately became shells.

VW: In some of these photographs, we see what you’re referencing. But what can we not see?

ER: What you can’t see in the photographs is the language. One of the more revealing pictures is of a man named Kevin working on Cedar Grove Ave. We went up to his house and there was a flag out front and a note about the marathon to people in the neighborhood — everyone was very mad that the marathon was going to happen.

And then out of the basement came this guy. We were very shy about approaching him — covered with dirt, steam coming off his head in the cold, with he and his wife cleaning out their entire house onto the pavement. He chose to write ‘Thanks Sandy’ on his house rather than the profanity that many would have written.

This is the way everyone was — [an attitude] you can’t see in the pictures. To feel the graciousness of everyone was surprising. Nobody was telling jokes, nobody was laughing, but there was much kindness. That’s what doesn’t show here: the calm utility of the people.

VW: How would you describe the disaster you witnessed over the weekend?

ER: In many cases, I think it’s the end of a way of life — the innocence is gone. Cedar Grove Beach — it was kind of a secret. You were close to the beach and it was beautiful…a very special opportunity for people who aren’t particularly wealthy to live a pretty good life.

Maybe that’s what speaks to us all. I don’t know about you, but the dream of all of us is to have a house on the beach. It’s my dream. I think that’s what speaks to a lot of people — these residents in their own way managed to live this dream and this is the result of it.

VW: You’ve photographed conflict and sadness throughout your career. How does this disaster compare to things you’ve witnessed elsewhere?

ER: It was different. Acceptance, first off, that this was nature — not a man-made tragedy. On the other hand, the difference is that people in other places I’ve gone to have nothing. These people [on Staten Island] had 20 to 30 years of things they’ve worked their asses off to have…the bulk of people were concerned with their photographs and irreplaceable personal things. The prom pictures, the family pictures, the few things they had left over from their heritage, their parents. That kind of thing was gone — much more devastating than anything else.

VW: One of your more powerful images is a pinboard of family photos that people had pulled out of the rubble.

ER: Curiously, I think in a way that the photographs have taken on another meaning, like proof that they exist in a certain way as people. Photographs have taken on a totem quality in our society, maybe more than they should. The photos do have a significance — that we exist and we have roots.

We were there when a man found a picture of his friend who died in 9/11 – a little snapshot. So he was very exceedingly happy.

VW: So in some ways, these photographs are proof of existence and proof of what used to be. Your photographs, then, amplify what these found objects are already saying.

ER: I think they were pleased that someone recognized they were alive.

Eugene Richards is an award-winning American photographer. LightBox previously featured his project and book, ‘War is Personal.’

Vaughn Wallace is the producer of LightBox. Follow him on Twitter @vaughnwallace.

More photos: The Toil After the Storm: Life in Sandy’s Wake

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com