Whenever the Valentine’s Day season rolls around, the topic turns love—and, inevitably, to the ways it can end. When I divorced seven years ago, California law allowed me to sever my marriage bond with no assignment of fault. With the aid of a mediator, we worked out financial support for my child, who was still a minor, and the splitting of our marital assets—all in the space of a few weeks. True, it took a few months for the divorce to become official, but I was free to immediately embark on a new life.

Had I divorced in 1952, the year my most recent novel is set, my experience would have been very different. Depending on the state where I resided, I would have to prove grounds for divorce, with no guarantee that a court would grant one. Two-thirds of U.S. states still treated property acquired during the marriage as being under the control of the husband. Those states that did grant divorce recognized grounds that were nearly impossible to prove, such as physical evidence of abuse, and some states did not allow remarriage.

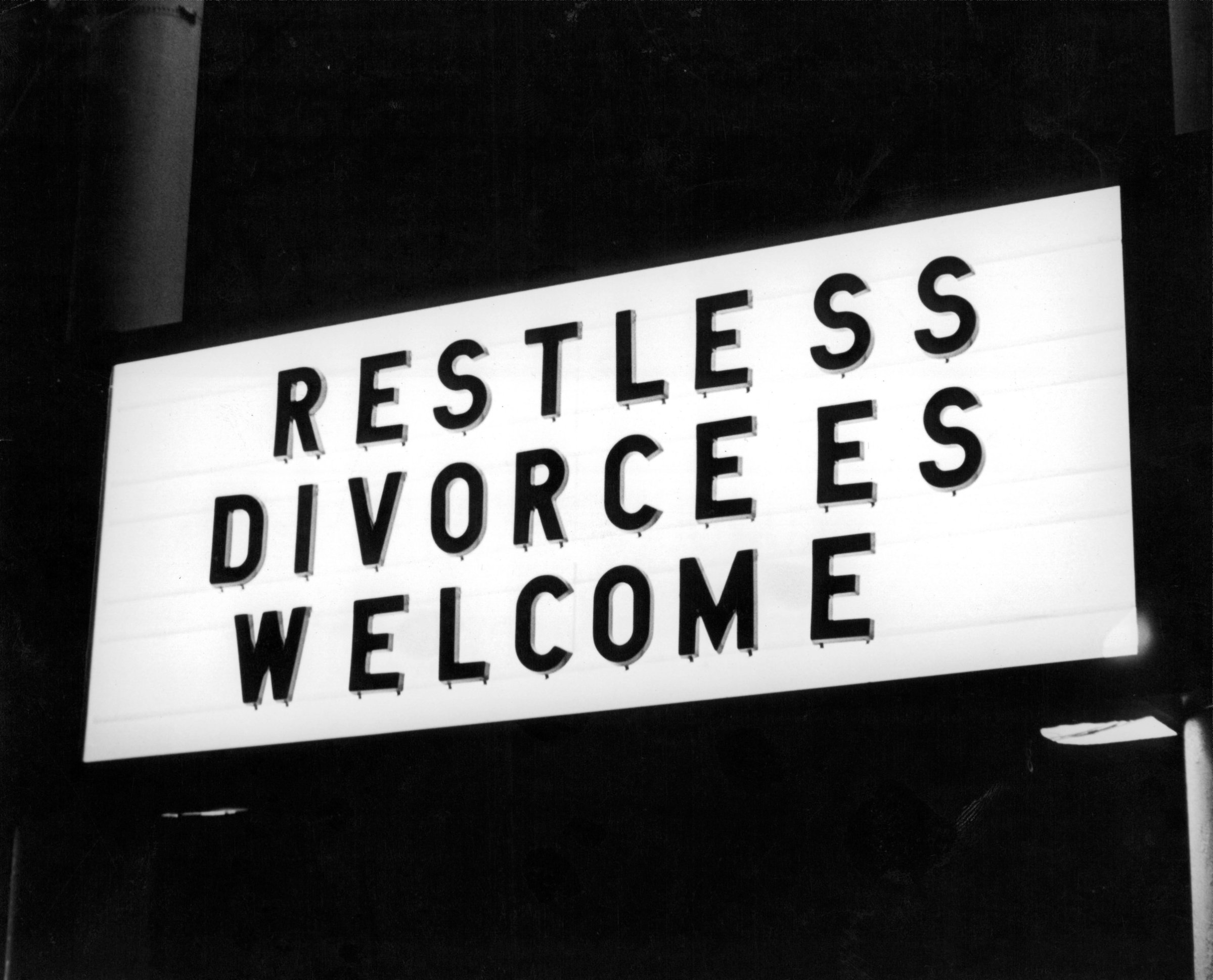

No wonder so many women, facing the prospect of a lengthy, arduous process and uncertain outcome, opted instead to go to Reno, Nev.—the city that, in tourist materials, proclaimed itself the “divorce capital of the world.” There, local laws meant they could establish residency in a mere six weeks and then expect a rubber-stamp decree no matter the circumstances of their split. The practice of seeking divorce in Reno dates back to the early 20th century, when the city shrewdly built lodging and entertainment steps from its courthouse, drawing a steady flow of “divorce tourists” looking to escape the East Coast press. By the 1950s, by which time Reno’s divorce laws had further loosened, a thriving economy had evolved for the sole purpose of meeting divorcees’ needs while they waited — and, indeed, Reno relied on the divorce trade to keep her coffers full.

Though the divorce rate has been in decline in the United States for some time, it rose steadily for most of the 20th century, peaking in the 1970s after most states adopted no-fault divorce laws. The rate in 2016 stood at 3.2 divorces per 1,000 people—18% fewer than in 2008. But underneath this overall rise and fall are several interesting shifts. The first divorce boom occurred right after World War II, with rates decreasing in the 1950s before beginning to rise again. The reason for an increase in post-war divorces is widely acknowledged to be rooted in women getting a taste of independence when, their husbands away fighting, they took jobs that were vacated by soldiers. Simply put, women were not inclined to give up their newfound independence easily, though whether they initiated divorce or their husbands did so in protest of their wives’ newly unruly natures is not clear.

The decline of the divorce rate in the 1950s owes to the idealization of the nuclear family, with rigid gender roles assigning women responsibility for staying home and raising children. It was a stifling relationship model for people who’d enjoyed a measure of acceptance in the fringes of society in prior decades, including LGBTQ people and those who were single by choice—and, we can safely assume, women who wanted more from life than the pervasive drudgery described by Betty Friedan a decade later in The Feminine Mystique.

That the majority of Reno divorce-seekers were women reflects the fact that men had jobs that kept them home, though many women found work in Reno, either by choice or necessity. A steady need for waitresses, laundresses, card dealers, clerks, maids and even ranch hands meant a girl could arrive with next to nothing and earn enough to pay her way. For many women, this was the first time they had money of her own to manage and spend.

If some new arrivals hoped to find an atmosphere of relaxed morals, where they might try their hand in a card room or go to a tavern unaccompanied by a man, Reno did her best to exceed these expectations. Hotels and ranches offered full calendars of entertainment including roulette lessons, singalongs, live music performances and even bawdy shows. A crop of male “drivers” made themselves available to escort the well-to-do, often partying with them long into the night. Dancing and flirting were the norm in many establishments, liquor was readily available and women’s inhibitions often vanished, especially since the system itself seemed to run on a winking disregard for social and even legal censure.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Another community flourished in Reno that, elsewhere in the country, conducted its business and pleasure in the shadows. Reno’s LGBTQ population enjoyed some measure of freedom and acceptance as early as the 1930s, when a Virginia Street bar called Belle Livingston’s Cowshed put on popular cross-dressing shows, while personal accounts from the mid-20th century make reference to a lesbian community that gravitated to the proliferating women-only lodging establishments. It is not unreasonable to imagine that some divorcees were leaving marriages that were not sexually suitable, and that they too may have found the freedom to explore in Reno.

By the early 1950s, the days of casual acceptance were numbered: The Cold War brought homophobia, transphobia and a police clampdown on suspect activities, including a ban on cross-dressing performances. And another sea change was beginning too—one that would see an end to this period in Reno’s history.

An early bill to change divorce law was penned by women and published in the Women Lawyers Journal in 1952, proposing that a divorce should be granted when a court finds “that there is no reasonable possibility of reconciliation … and that the welfare of [the husband, wife, and children, if any] will be promoted by the divorce.” In the years that followed, with the advent of Family Court and a move toward this “no fault” mode of divorce, laws began to change across the country. Eventually, there was no need to go to Nevada to end a marriage. Every U.S. state now offers no-fault divorce, and Reno’s reputation faded—but it hasn’t been very long since splitting from one’s spouse could most easily be accomplished by an adventure in Reno.

Sofia Grant is the author, most recently, of Lies in White Dresses, a novel about “the Reno cure.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com