It was the first summer of the Civil War, and everyone thought it would be the last. Hundreds of thousands of Americans converged on train platforms and along country roads, waving handkerchiefs and shouting goodbyes as their men went off to military camps. In those first warm days of June 1861, there had been only a few skirmishes in the steep, stony mountains of western Virginia, but large armies of Union and Confederate soldiers were coalescing along the Potomac River. A major battle was coming, and it would be fought somewhere between Washington, D.C., and Richmond.

In the Union War Department a few steps from the White House, clerks wrote out dispatches to commanders in California, Oregon and the western territories. The federal government needed army regulars currently garrisoned at frontier forts to fight in the eastern theater. These soldiers should be sent immediately to the camps around Washington, D.C.

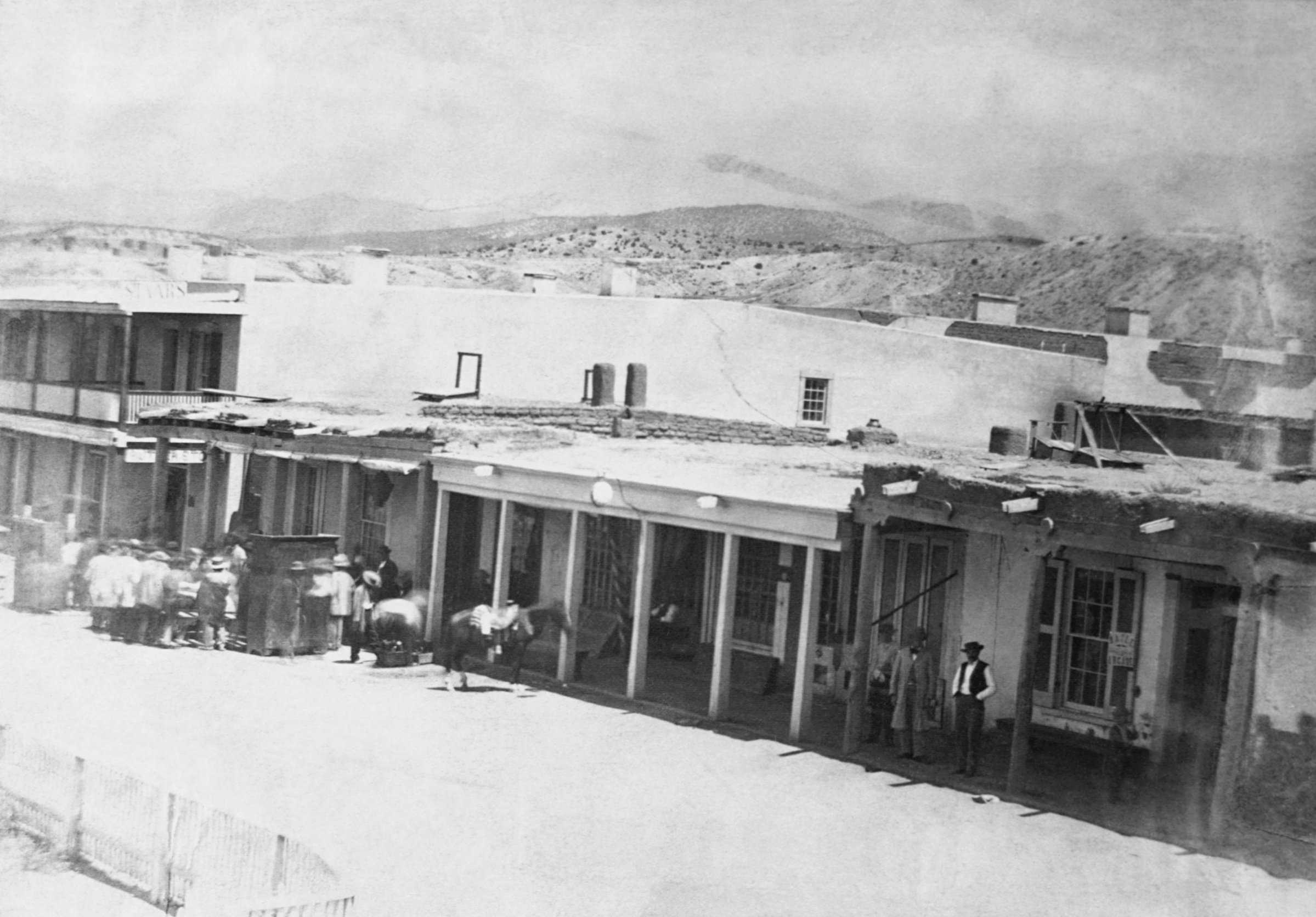

In New Mexico Territory, however, some regulars would have to remain at their posts. The political loyalties of the local population—large numbers of Hispano laborers, farmers, ranchers and merchants; a small number of Anglo businessmen and territorial officials; and thousands of Apaches and Navajos—were far from certain. New Mexico Territory, which in 1861 extended from the Rio Grande to the California border, had come into the Union in 1850 as part of a congressional compromise regarding the extension of slavery into the West. California was admitted to the Union as a free state while New Mexico, which was south of the Mason-Dixon Line, remained a territory. Under a policy of popular sovereignty, its residents would decide for themselves if slavery would be legal. Mexico had abolished black slavery in 1829, but Hispanos in New Mexico had long embraced a forced labor system that enslaved Apaches and Navajos. In 1859 the territorial legislature, made up of predominantly wealthy Hispano merchants and ranchers with Native slaves in their households, passed a Slave Code to protect all slave property in the Territory.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In order to ensure that this pro-slavery stance did not drive New Mexico into the arms of the Confederacy, the commander of the Department of New Mexico would have to keep most of his regulars in place to defend the Territory from a secessionist overthrow, as well as a possible Confederate invasion of New Mexico. Union officials wanted more Anglo-Americans to settle in New Mexico Territory at some point in the future, in order to colonize its lands and integrate the Territory more firmly into the nation. As the Civil War began, however, they wanted to control it as a thoroughfare, a way to access the gold in the mountains of the West and California’s deep-water ports. They needed the money from the mines and from international trade to fund their war effort. The Confederates wanted these same resources, of course. In the summer of 1861, Union forces had to defend New Mexico Territory in order to protect California, and the entire West.

Edward R. S. Canby, the Union Army colonel who was in control in Santa Fe, hoped that in addition to his army regulars, he could enlist enough Hispano soldiers to fight off an invading Confederate Army. To recruit, train, and lead these soldiers the Union Army needed charismatic officers, men who could speak Spanish and who had experience fighting in the rolling prairies, parched deserts, and high mountain passes of the Southwest. Several such men volunteered for the Union Army in the summer of 1861, including Christopher “Kit” Carson, the famed frontiersman. Carson had been born in Kentucky but had lived and traveled throughout New Mexico for more than thirty years, working as a hunter, trapper, and occasional U.S. Army guide. He volunteered for the army when the Civil War began, accepting a commission as a lieutenant colonel. In June 1861, Canby sent him to Fort Union to take command of the 1st New Mexico Volunteers, a regiment of Hispano soldiers who had come into camp from all over the Territory. Carson knew that most of New Mexico’s Anglos were skeptical about these men and their soldiering abilities. The frontiersman believed, however, that the soldiers of the 1st New Mexico would fight well once the battles began. His job was to get them ready.

Some of Carson’s men came with experience, having served in New Mexican militias that rode out to attack Navajos and Apaches in response to raids on their towns and ranches. It was a cycle of violence with a long history, one that predated the arrival of Americans in New Mexico. That summer, however, as soldiers gathered in Union military camps, there had been few raids into Diné Bikéyah, the Navajo homeland in northwestern New Mexico. The calm was unusual, but welcome.

The Navajos were not the only ones who noticed a shift in the balance of power in the summer of 1861. In the southern reaches of New Mexico Territory, the Chiricahua Apache chief Mangas Coloradas watched Americans move through Apachería, his people’s territory. This was the latest in a series of Anglo migrations through Apachería over the past 30 years. Mangas decided that these incursions would not stand. In June 1861, sensing that the U.S. Army was distracted, he decided that this was the time to drive all of the Americans from Apachería.

Step Into History: Learn how to experience the 1963 March on Washington in virtual reality

Navajos and Chiricahua Apaches were a serious challenge to the Union Army’s campaign to gain control of New Mexico at the beginning of the American Civil War. If Canby could secure the Territory against the Union’s Confederate and Native enemies, he would achieve more than Republicans had thought possible after ten years of constant, angry debates about the introduction of slavery into the West, and the significance of that region in the future of the nation. Would the West become a patchwork of plantations, worked by black slaves? Southern Democrats, led by Mississippi senator (and future Confederate president) Jefferson Davis, had argued that the acquisitions from Mexico, particularly New Mexico Territory, “can only be developed by slave labor in some of its forms.” The amount of food and cotton that New Mexico plantations would produce, Davis imagined, would make that Territory a part of “the great mission of the United States, to feed the hungry, to clothe the naked, and to establish peace and free trade with all mankind.”

Members of the Republican Party disagreed. A relatively new political organization born out of disputes over slavery in 1854, Republicans considered slavery to be a “relic of barbarism” and argued that it should not be expanded into the western territories. “The normal condition of all the territory of the United States is that of freedom,” their 1860 party platform asserted. Preventing Confederate occupation of New Mexico Territory and clearing it of Navajos and Apaches were twin goals of the Union Army’s Civil War campaign in New Mexico, an operation that sought not only military victory but also the creation of an empire of liberty: a nation of free laborers extending from coast to coast.

As those determined to make that dream a reality — and those determined to prevent it from becoming one — converged in New Mexico Territory in 1861, a comet appeared overhead, burning through the desert sky. Astronomers speculated about its origins. It could be the Great Comet of 1264, the huge and brilliant orb that had presaged the death of the pope. Or it might be the comet of 1556, whose tail resembled a wind-whipped torch, and whose splendor had convinced Charles V that a dire calamity awaited him. In either case, the editors of the Santa Fe Gazette found the appearance of this “new and unexpected stranger” in the skies to be ominous.

“Inasmuch as bloody [conflicts] were the order of the day in those times,” their report read, “it is easy to see that each comet was the harbinger of a fearful and devastating war.”

Excerpted from The Three-Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West by Megan Kate Nelson, available now from Scribner.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com