California Gov. Gavin Newsom on Wednesday posthumously pardoned the openly gay civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, who was charged with vagrancy and ordered to register as a sex offender in 1953 for having consensual sex with another man.

Rustin was arrested in Pasadena, Calif., and sentenced to 60 days in jail for the misdemeanor “morals charge” after a police officer found him having sex with a man in a parked car. Rustin had been in Pasadena to deliver a speech on world peace.

The pardon, which comes more than 30 years after Rustin’s death — he died in 1987 after going into cardiac arrest following an appendix surgery — is an effort to correct a “long and reprehensible history,” Newsom said.

“California, like much of the nation, has a disgraceful legacy of systematically discriminating against the LGBTQ community. This discrimination has taken many forms including social isolation and shaming, surveillance, intimidation, physical violence, and unjust arrest and prosecution,” Newsom said in the official pardon. “Mr. Rustin was sentenced pursuant to a charge commonly used to punish gay men for engaging in consensual adult sexual conduct. His conviction is part of a long and reprehensible history of criminal prohibitions on the very existence of LGBTQ people and their intimate associations and relationships.”

Newsom also issued an executive order creating a clemency process to pardon other people who were similarly “subjected to discriminatory and unjust arrest and prosecution for engaging in consensual adult sexual conduct.”

California’s penal code at the time was similar to those in many other states across the country, with laws against sodomy, lewdness and indecency in public and private often used to target LGBTQ people. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled anti-sodomy laws unconstitutional in 2003.

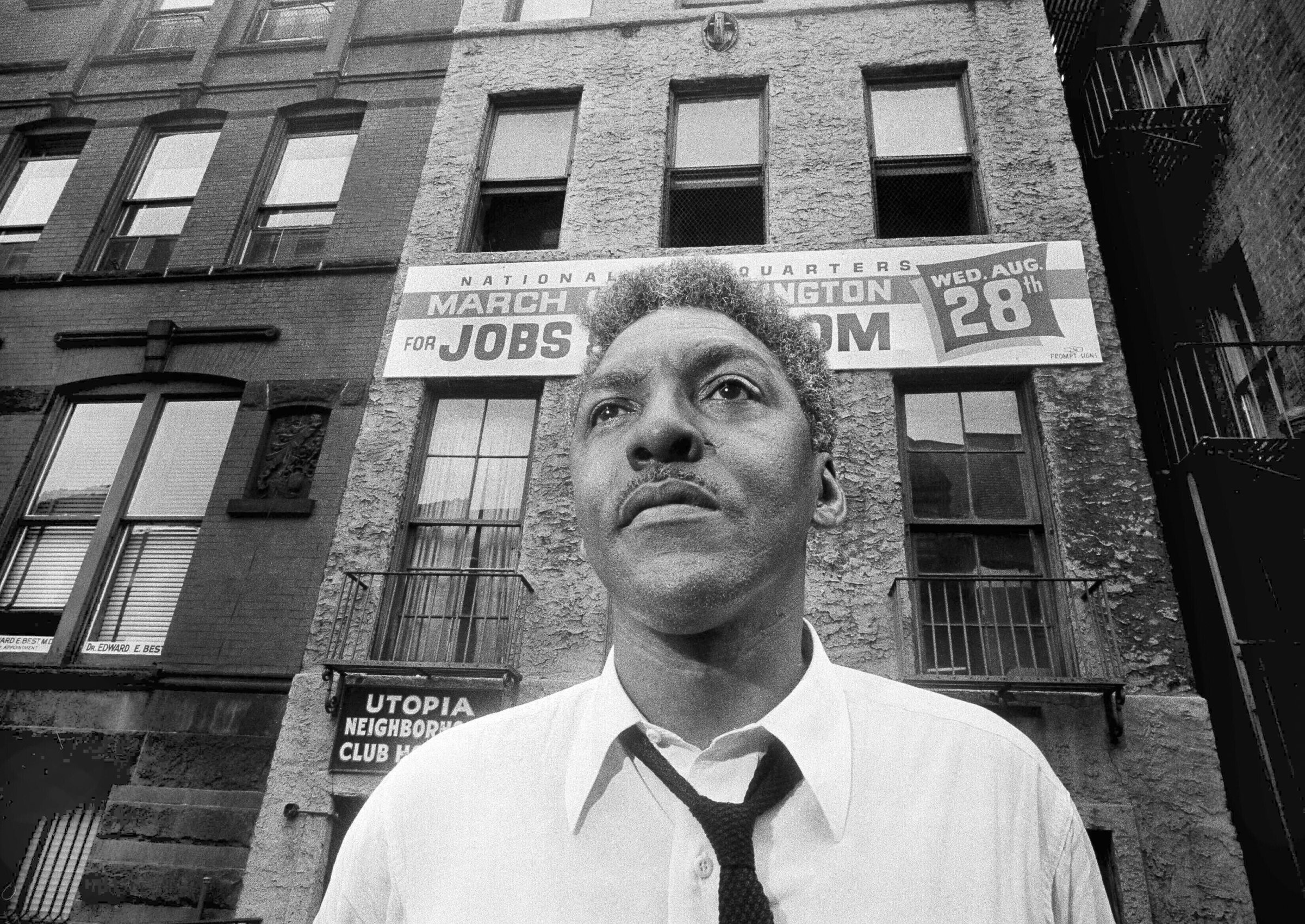

Rustin—who Newsom called “a visionary champion for peace, equality and economic justice”—organized the 1963 March on Washington and was a key adviser to Martin Luther King Jr., throughout the civil rights movement. But he was often sidelined because of his sexuality.

Read more: Experience The March on Washington in Virtual Reality

“At a given point, there was so much pressure on Dr. King about my being gay — and particularly because I would not deny it — that he set up a committee to explore whether it would be dangerous for me to continue working with him,” Rustin said in an interview with the Washington Blade in the 1980s, which aired for the first time on the Making Gay History podcast last year. (In an effort to discredit the March on Washington and undermine the civil rights movement, segregationist South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond used the misdemeanor charge and Rustin’s sexuality against him, reading it into the congressional record and accusing him of “sex perversion.”)

But Rustin also said he felt a responsibility to be open about his sexuality.

“It was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality, because if I didn’t I was a part of the prejudice,” Rustin said. “I was aiding and abetting the prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me.”

“For decades, this great leader, often at Dr. King’s side, was denied his rightful place in history because he was openly gay,” former President Barack Obama said in 2013, when he awarded Rustin with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

State lawmakers and LGBTQ rights activists had called on Newsom to pardon Rustin earlier this year — including state Sen. Scott Wiener, chair of the California Legislative LGBTQ Caucus, and state assemblywoman Shirley Weber, chair of the California Legislative Black Caucus.

“There’s a cloud hanging over him because of this unfair, discriminatory conviction, a conviction that never should have happened, a conviction that happened only because he was a gay man,” Wiener told the Washington Post last month. He celebrated the pardon in a tweet on Wednesday. “Big win for justice,” he said

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com