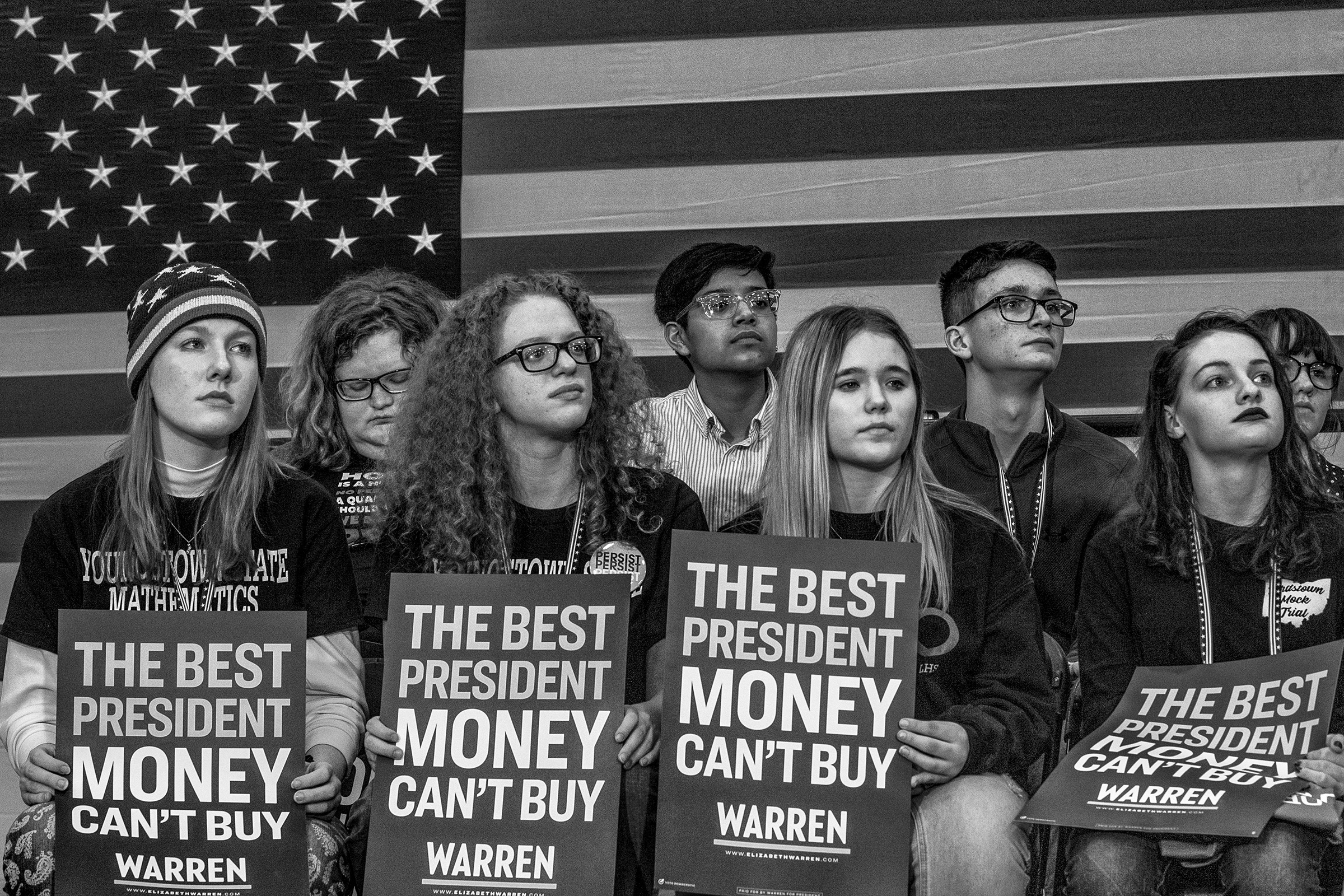

Pacing the stage of a packed high-school gym, Elizabeth Warren is recounting how she deals with naysayers. Naturally, she says, the lobbyists and the billionaires don’t like her proposals. But “this is democracy!” she says. “There’s a whole lot more of us than there is of them.”

From somewhere in the crowd, a man shouts, “WOO!”, and Warren grins. “See?” she says. “That resonates!

For a moment last fall, Warren seemed to be in prime position to win Iowa, whose caucuses will kick off the Democratic primary on Feb. 3. But she seems to have fallen behind since then, as lefty voters gravitate toward a surging Bernie Sanders and moderates rally behind Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg or Amy Klobuchar. In polling averages, Warren has fallen into fourth, behind Buttigieg.

Iowa could be make-or-break for Warren, who needs a comeback here to re-establish herself as a top candidate. And she’s campaigning like she knows it, rolling out a forceful new pitch that stresses transcending the Democratic Party’s divisions and arguing that her populist platform would best attract crossover votes come November.

Across the political spectrum, she argues, voters feel frustrated that the economy is rigged against ordinary people. They’re angry that corporations rake in billions in profits yet pay little or no federal taxes. “It’s very popular—among Democrats, among independents, among a majority of Republicans,” she says of her proposal for a 2% tax on wealth above $50 million.

New signs have appeared at Warren’s events: “UNITE THE PARTY,” they say. It’s an overt attempt to appeal to voters exhausted by the nastiness and squabbling that have erupted in some quarters, and also perhaps a belated acknowledgement that Warren has been damaged by the perception that her liberal agenda is indistinguishable from Sanders’s. Her closing ads make the same argument, featuring voters who supported both Sanders and Hillary Clinton four years ago coming together around her candidacy.

There’s plenty of room for an upset: the top four candidates are bunched tightly together in most polls, with no candidate receiving even a third of the vote and many voters still undecided about their final choice. Warren has spent millions over the past year building a massive field organization to turn out her voters.

“Her ground game’s the best in the state,” says John Norris, a veteran Democratic operative, former state party chairman and former chief of staff to former Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack. “But that may not be as much of an advantage as usual because people are so frozen in indecision.”

Norris argues that Warren would be a more formidable general-election candidate than Biden because she generates more enthusiasm. “It’s hard to go to your neighbor in the fall and say, ‘Vote for Joe Biden because he’s electable,’” Norris says. “That’s not a reason. It’s inane.”

Warren has also been making an explicit argument about gender. She contends a woman at the top of the ticket would be an asset for Democrats. “The world changed when Donald Trump got elected,” she told reporters backstage after her speech in Iowa City on Saturday. “Women candidates helped us win back the House in 2018 and won a lot of statehouse races in competitive elections.”

Warren and her allies are trying to beat back the idea that sexism in the electorate would hurt her chances against Trump. It’s something Courtney Johnson, a 27-year-old social worker and Warren volunteer, says she commonly hears while knocking on doors in her hometown of Cedar Rapids.

“I tell them I think America is ready for a woman president, and it’s time to show that we are,” Johnson says. “I tell them, don’t caucus according to what someone else might think—vote for the candidate you like. People like her. They just have doubts about whether she can win.”

Warren’s closing pitch has been complicated by Trump’s impeachment trial, which trapped her in Washington for crucial weeks in January, along with fellow candidates Sanders, Klobuchar and Michael Bennet. Over the weekend, she rushed to make up for lost time, apologizing that she couldn’t stay for her usual lengthy photo sessions with supporters because she had to make it to her next event. Her golden retriever Bailey, a campaign celebrity, stayed to be photographed in her stead.

Warren appeared to seal the deal with some waffling voters. “I came here trying to finalize my vote, and I’m leaving convinced,” said Sarah Gardner, a 43-year-old urban planner in Davenport, Iowa. Gardner likes Warren’s policies but was worried about whether she would be able to communicate them to ordinary people across the political spectrum; seeing Warren’s passion and energy convinced her.

“The stakes are so high with this election,” says Gardner, who supported Sanders four years ago. “We have a president who only seems to represent the people who voted for him. I’m looking for someone who will be president of the whole country.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Molly Ball/Iowa City at molly.ball@time.com