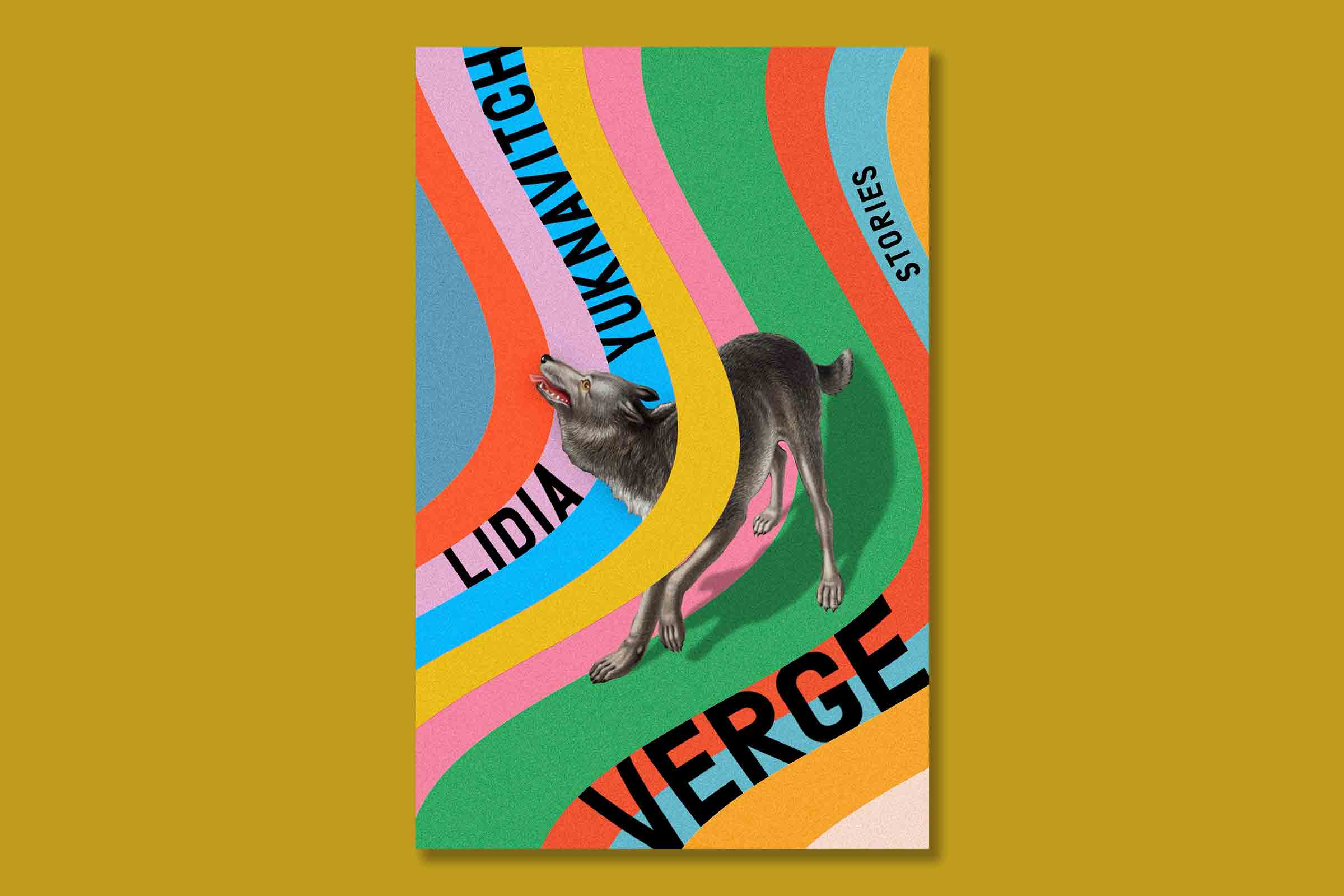

Lidia Yuknavitch, author of such celebrated books as The Book of Joan and The Small Backs of Children, once presented a viral TED talk titled “The Beauty of Being a Misfit.” The characters in Verge, her new collection of short stories, are misfits too: rejects and refugees and runaways and an addict turned yuppie, all of whom are desperate to make sense of the alienation that separates them from their families, from society or from their own bodies.

In “The Organ Runner,” an Eastern European girl whose hand is medically reattached after a combineharvester accident becomes a talented transporter of blackmarket human organs, before exacting a grim revenge. In “Cosmos,” a janitor at a planetarium uses the detritus he finds discarded under the auditorium seats to construct a fantasy city on his diningroom table in his offhours. “He saw that his superficial efforts with refuse were the key,” Yuknavitch writes, “that decay itself was the giver of life, the secret of the universe, the place from which all stars collapse and all systems tower and all logic gets born and then falls.” And in “Cusp,” a young woman experiments with her burgeoning agency by smuggling drugs to the men in a nearby prison, where her brother finds himself incarcerated.

But the collection’s slim masterpiece is “Beatings,” a short, bodily stunner of a story about a man with a heart condition who spends his time boxing a heavy bag and playing the cello. While he is boxing, “Ideas seize, recede, then again raise and rise. Fisted speed dug deep and jab extended until it is shot strung back to the shoulder.” And while making music, “His fingers carry the crouch of a dream in which chaos orders and slows and sings … the notes rebody a body.” With the powers of her prose on full, incandescent display, 6½ pages is all Yuknavitch needs to illuminate the connections between the body and the spirit, the fists and the heart, both beating in their losing battles.

In these 20 efficient and affecting stories, Yuknavitch unveils the hidden worlds, layered under the one we know, that can be accessed only via trauma, displacement and pain. There is a vein of the wisdom of the grotesque throughout; as one character reflects after harming herself, “this was all a little disgusting, the kind of story that would make the listener lean a little away from her.” But the damaged beauty of these misfits keeps the reader leaning in.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com