If modernism sought to give us Le Corbusier’s “machine for living [in],” photographer Ezra Stoller, who died in 2004, used the camera as a machine for living through. His work was not only so comprehensive that it documented modernism’s rise, but was a part of the modernist movement itself. Now, a new book “Ezra Stoller, Photographer” aims to showcase both the images that made him famous, and those that tend to get less exposure. Co-authored by his daughter Erica Stoller, who manages Esto, the photographic agency he founded in 1966, and architectural writer Nina Rappaport, the tome presents Stoller’s iconic images alongside lesser known industrial photography that has a strikingly different focus from his shots of buildings alone.

Like the spaces he captured, his work is clean, simple and elegant. In one frame Stoller could distill the essence of a structure, as if he knew how to perfect the architect’s dream. His shots of Eero Saarinen’s TWA terminal at John F. Kennedy Airport, for example, seem both fluid and solid at once—a feeling often hard to experience in the building itself. Stoller was known for being meticulous, pedantic even. With large format cameras, a Deardorff in the 1930s and 1940s and a Sinar in the 1950s and 1960s, as we learn from the book, he would reportedly stay in spaces for days before he photographed, and would often turn up to shoot just after a building was finished. Among architects, his name was used as a verb; to have a design “Stollerized” was seen as a great honor. Indeed, his client list reads like a who’s who of mid 20th Century architecture: Frank Lloyd Wright, Philip Johnson and Louis Kahn, to name but a few.

It may come as a surprise, then, to learn that Stoller didn’t consider himself an artist. Trained as an industrial designer at New York University, Stoller came into the workforce during the Great Depression, a factor that saw him eschew a design career for one behind the camera, a discipline he had no education in. A move perhaps stemming from his token perfectionism: he didn’t have too many industry-related connections and hated the idea of working for another architect. He saw photography as a practical way to excel.

“He decided that this was going to be the medium that he could best speak about architecture,” Erica Stoller says. “By moving to the side he felt that he could contribute more. He got to be involved with architects making decisions,” she adds.

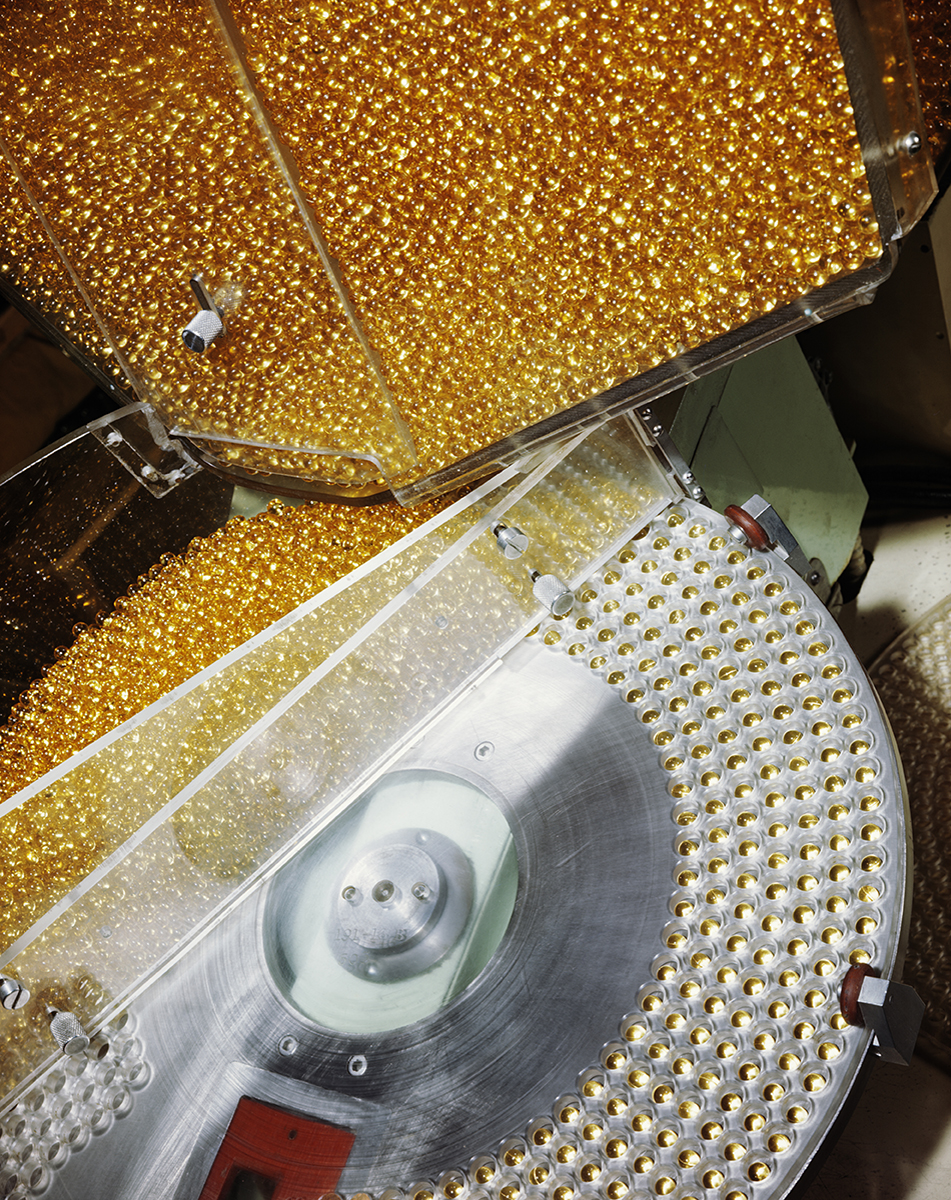

Sometimes projects for magazines such as Fortune, other times commissions for companies such as IBM, Stoller’s lesser-known images are part social realism, part modernist idealism. In these posed shots we see the working man as hero, the working woman as heroine, and both at the center of the industrialist dream. They are optimistic, sharp, beautiful, and they show us the true breadth of his work: he was not just an architectural photographer but an industrial and portrait photographer too. “They are images of industry in America, and he is really focused on the worker in motion,” Rappaport says. “This was all post-war. It was a time of prosperity, and he really captures this.”

Ezra Stoller, Photographer will be published by Yale University Press on Nov. 19.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com