David Stern’s worst day in his 30-year tenure as NBA commissioner was also his best. On November 7, 1991, Stern took an early plane from New York City to Los Angeles, to sit by Magic Johnson’s side at a press conference as Magic told the world that he was HIV-positive and retiring from basketball. Like many people, Stern figured that Johnson was going to die. And on that flight, he thought about how people within basketball would react to the fact that he was lending his support to someone who was HIV positive. At the time, the disease was misunderstood and demonized. People thought you could “catch” AIDS if someone sweat on you. Stern could have distanced himself from the superstar. He could have moved on from Magic.

But he got on that flight and had Magic Johnson’s back. Stern read the medical literature, talked to experts, and dispatched doctors to NBA teams, some of whom were nervous that Johnson wanted to play in the 1992 NBA All-Star game, and in that summer’s Olympics. Stern helped enlighten owners, players, sponsors—and the world—about the defining public health crisis of that era.

“When I announced in 1991 I had HIV, people thought they could get the virus from shaking my hand,” Magic wrote on Twitter after Stern passed away, at 77, on Wednesday following a brain hemorrhage he suffered on Dec. 12. “When David allowed me to play in the 1992 All Star Game in Orlando and then play for the Olympic Dream Team, we were able to change the world.”

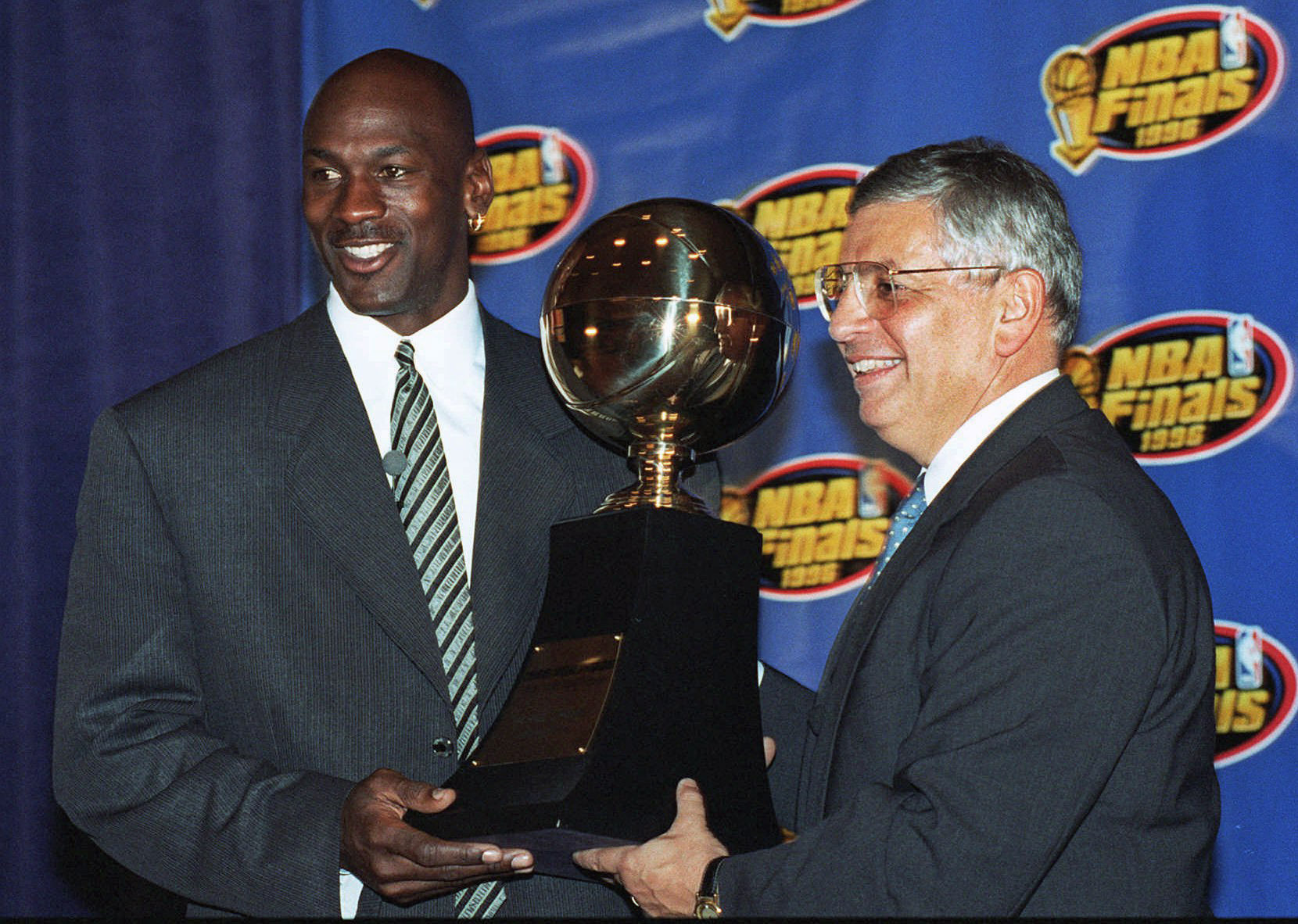

Stern helped expand basketball’s influence beyond anyone’s imagination, and will be remembered as one of the most impactful, and successful, commissioners in professional sports history. When he took over the NBA in 1984, he was tasked with repairing a damaged product. “We had the drug issue,” says NBA Hall-of-Famer Alex English, the league’s scorer in the 1980s, referring to rising rates of cocaine use among players. “Our image was rough. We were on tape delay. People thought the league was too black.” But by promoting stars like Johnson, Michael Jordan and Larry Bird, stabilizing the NBA’s business model and seeing the league’s potential beyond American borders, Stern—a demanding boss unafraid to raise his voice or tick people off in pursuit of league interests—helped transform the NBA into today’s multi-billion-dollar colossus that is enjoyed around the globe.

Golden State Warriors president Rick Welts, who worked for Stern in the NBA league office from 1982 to 1999, calls Stern “the single most important individual” in the history of the NBA. “I don’t think there’s an argument,” Welts tells TIME. “With all due respect to Bill Russell, Michael Jordan and LeBron James, we would not have the NBA that we have today without his genius. We see the results today and assume that the NBA was always like this, which if course it wasn’t.

“It was his pure will and determination, and his incredibly difficult nature, that moved mountains and got people to believe, through the pure force of his personality, that you can pushed this gigantic boulder up the hill. There’s nobody else who could have done that.”

Even those Stern clashed with as commissioner recognized his positive impact on the league. “David had a global vision that recognized that technology would make the world a smaller place and the NBA was better suited to reach every continent than any other sport,” Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, whom Stern fined at least 20 times during his tenure, writes in an email to TIME. Many of the penalties, which cost Cuban some $1.9 million, concerned Cuban’s spats with referees.

“Some executives only have the vision, David knew how to execute on that vision,” writes Cuban. “What made it ever more amazing was that he never wavered no matter what other struggles the league had to address. He took them on, took total responsibility, resolved then as best he could and always kept moving the NBA forward. All that said, what I liked best about David is that we could have knock down drag out arguments about anything and still have respect for each other and still be friends. I really loved the man and learned so much from him. It’s a sad day.”

Stern grew up in New Jersey as a New York Knicks fan, and joined the NBA as general counsel in 1978 from the Proskauer Rose law firm, where he was a litigator. His impact on the modern NBA began even before he formally took over as commissioner. As executive vice president of the league in 1983, he negotiated a pioneering salary cap agreement with the players that put a limit on annual payroll spending but also established revenue sharing between owners and players, which enabled salaries to grow over time as the league succeeded. “It went a long way to saving the league at the time, as it allowed us to attract capital for certain teams, like Denver, Indiana, Cleveland, Utah and others, that were in some trouble,” says former deputy NBA commissioner Russ Granik. “Even though our first salary cap was far from perfect, it was an important step in working with the players to put the league on sound business footing.”

Another crucial move was instituting an anti-drug agreement resulting in harsh penalties for repeated violations. In 1986, for example, Stern banned All-Star point guard Michael Ray Richardson for life for cocaine use. The punishments helped deter drug use and offered corporate sponsors comfort that the NBA was refurbishing its reputation. With more money flowing into the league office, Stern could spend it on marketing the star players and rivalries he was fortunate to inherit—like the Bird-Magic clashes in the three Boston Celtics-Los Angeles Lakers NBA Finals between 1984-1987. “Stern had an army of folks that put his plan into action,” says English, who in the early 1990s joined Stern on a trip to South Africa, where they met Nelson Mandela.

“What he wanted to get done when he went into a room usually got done,” says Rod Thorn, the NBA’s executive vice president of basketball operations from 1986-2000. “That is a knack. We talk about players having different skills. That was a heck of a skill he had.”

For example, when the Olympics decided to open up its basketball competition to NBA players before the 1992 Games in Barcelona, some owners weren’t totally on board with the idea. They worried about injuries. Some media members offered pushback. A “Dream Team” of American stars, winning every game by 50 points, could make a mockery of the competition.

Stern, however, convinced stakeholders that the NBA’s Olympic participation would show his product off to the world. “No one tells Finland not to send its best ski jumpers,” says Granik. “Why are you picking on basketball?”

The 1992 “Dream Team,” which featured Jordan, Bird, Magic and Charles Barkley, inspired a generation of international athletes to swap soccer for basketball. The 2019 opening night NBA rosters featured 108 international players from 38 countries and territories. NBA games are available on television in more than 200 countries worldwide. “When you’re a kid in the back yard and you’re hooping, you’re thinking about playing in the NBA in front of your friends and family,” Oklahoma City Thunder point guard Chris Paul, who entered in the NBA in 2005 and serves as president of the NBA Players Association, tells TIME. “You never knew you would play in China, or you would play in Spain, or you would play in Germany and all these different places. For guys who didn’t have an opportunity to know him or understand his impact on the business of the game, I hope they get an opportunity to see it.”

Some of Stern’s decisions caused a backlash. In 2005, the NBA instituted a dress code for players on the bench but not in uniform; many African-American players felt unfairly targeted. (Though now, a consensus has emerged that Stern’s “business casual” mandate has spawned an NBA fashion revolution). When the NBA temporarily took over ownership of then New Orleans Hornets (now Pelicans), Stern vetoed a trade of Paul to the Los Angeles Lakers, which critics considered meddling in team affairs. Labor peace was elusive: a lockout-shortened the 1999 season and set the league back, and tense collective bargaining negotiations of 2011, which resulted in a 161-day lockout and shortened 2011-2012 season, grew particularly cantankerous. “You’re not pointing your finger at me,” Miami Heat star Dwyane Wade reportedly shouted at Stern in one session. “I’m not your child!”

“We had some interesting times, some interesting times,” says Paul, a key player rep in those 2011 talks, with a laugh. “One thing about David, he was going to give it to you straight. Good, bad, or indifferent.” Paul says that the gains that came after the 2011 negotiations—such as the record $24 billion TV deal the NBA signed with ESPN and Turner Sports a few years later—ultimately outweighed any hard feelings.

“Everybody had a complicated relationship with David,” says Welts, who in 2011 became the first major sports executive to come out as gay, with Stern’s unwavering support. “I used to joke that the greatest success of my life was directly reporting to David Stern for 17 years and living to tell about it. He was just so passionate about the things he cares about. He would not have the softest touch. But there was this incredible soft and compassionate side of him. I’d get home from a tough day at work, so upset at this guy who thinks I’m the most incompetent person in the world, and at 10 p.m., Uncle Dave would call and ask how I was doing. And suddenly I couldn’t wait to charge through the door in the morning to make something great. He really knew how to get the best out of people.”

Stern announced in 2012 that he would step down as commissioner after he completed his 30th year on the job, in February of 2014. On a conference call that day, he gave his own epitaph a shot. He nailed it. “I’m not a big believer in the L word, legacy,” Stern said then. “I just want people to say that he steered the good ship NBA through all kinds of interesting times, some choppy waters, some extraordinary opportunities, and … on his watch, the league grew in popularity, became a global phenomenon and the owners and the players and the fans did very well.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com