When you think of early expeditions to the Polar North, images of hardship, deprivation, frostbite and death usually come to mind. These were the realities of the 19th Century attempts to the deadly region, where steering ships through the harsh, ice-bound labyrinth resulted in average crew losses of 50 percent. Some never came home, as with Sir John Franklin’s famous 1845 voyage seeking the fabled Northwest Passage, in which he and his entire crew of 129 vanished. But there was one lesser-known expedition—The Greely Expedition—during which (at least in the beginning), the men enjoyed warm shelter, sumptuous, opulent meals, singing and revelry and holiday celebration at the far end of the earth.

In 1881, an ambitious Lieutenant and acting U.S. Signal Corps Officer named Adolphus W. Greely led an unprecedented journey to the Arctic. Formally called The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition (named for Franklin’s dutiful wife Lady Jane Franklin, who for years hounded the British Admiralty to search for her missing husband and his men), it has come to be known as The Greely Expedition.

The mission was threefold: They were to collect scientific data for the first International Polar Year; they were to search for and hopefully rescue the men of the lost USS Jeannette, which had disappeared two years earlier; and last, Greely secretly intended to venture into the unexplored Lincoln Sea and become the first to reach the North Pole. Should he fall short, he would try to attain Farthest North, an explorer’s holy grail of the highest northern latitude, which had been held by the British for three hundred years.

If he succeeded, he would return a national, even global hero.

In early August of 1881, Greely and twenty-four explorer-scientists landed at Discovery Harbor, on the far north-eastern edge of what was then known as Grinnell Land, now known as Ellesmere Island, Canada. The crew hurriedly unloaded the steamship Proteus. They off-loaded enough pre-cut timber to build a spacious, double-walled longhouse sixty-five feet long, twenty-one feet wide, and fourteen feet tall. It would have a kitchen, two stoves, comfortable quarters for the officers and bunkrooms for the men.

Greely set the men to work around the clock in four-hour shifts, made possible by the perpetual sunlight. There was no time to waste: by mid-October, the skies would darken, and the sun would not return again for 130 days. Temperatures would plunge to minus 75-degrees Fahrenheit.

Within two-weeks, the structure, dubbed Fort Conger, was nearly complete. Located 250-miles north of the last known Eskimo settlement and 1,000 miles north of the Arctic Circle, Greely and his men were now the most northerly colony of human inhabitants in the world.

They had enough food for a three-year stay, with nearly thirty thousand rations of various meats—including pork and pemmican (a high- calorie mixture of dried meat, melted fat, and often berries), bacon, ham, and mutton—as well as canned salmon, cod, and crabmeat. Greely had brought along some forty thousand rations of beans and rice, plus two thousand pounds of potatoes packed in five-pound cans, and mixed vegetables in two-pound cans, including pickles, onions, and beets. There were preserved peaches, molasses and syrup, canned pork and beef, as well as foods thought to thwart scurvy: immense quantities of dried fruits, damsons and other plums, and cranberry sauce.* They also brought many casks of rum, whose restorative properties were considered more necessity than luxury.

In mid-October the sun set, giving way to “the long night,” the polar effect of perpetual twilight. But although the polar winter was devoid of sun, it was not devoid of light. Every two weeks the men were transfixed by the appearance of the magical northern lights, or aurora borealis, a phenomenon of bright and sometimes dancing lights that result from collisions between gaseous particles in the Earth’s atmosphere with charged particles released from the sun’s atmosphere. Greely noted displays that were “grand and magnificent in the extreme,” including “lances of white light, having perhaps a faint tinge of golden or citron color, which appeared as moving shafts or spears,” and one that looked like “a pillar of glowing fire, from horizon to horizon through the zenith, showing at times a decidedly rosy tint, and later a Nile-green color.” Sometimes while watching this spectacle, men would see the ghostly outline of polar bears traversing the shore and the ice foot, and Greely was reminded of recent wolf attacks. The men would need to be always alert, for danger lurked everywhere.

To help stave off “cabin fever” or “polar madness”—which could drive men into deep melancholy and even suicide—Greely organized elaborate holiday celebrations. The first Thanksgiving at Fort Conger proved memorable indeed. After being mostly fort-bound for weeks, Greely organized a series of races, contests, and competitions. All the men participated in one way or another, either as contestants, judges, or coaches. Illuminated all day by a series of auroral streamers of fluctuating brilliance, the men competed in snowshoe races, footraces, sled-dog races, and finally, a shooting competition.

The first Thanksgiving menu was extravagant, as follows: “Oyster soup, salmon, ham, eider ducks, devilled crab, lobster-salad, asparagus, green corn, several kinds of cake and ice-cream, dates, figs, and nuts.” Greely and the other officers sipped Sauternes from his private supply, and he gave “a moderate amount of rum . . . to the men in the evening, which contributed much to the merriment of the day.” During the meal, prizes were distributed to the winners of the day’s events, and the evening concluded with concertina and violin music and singing.

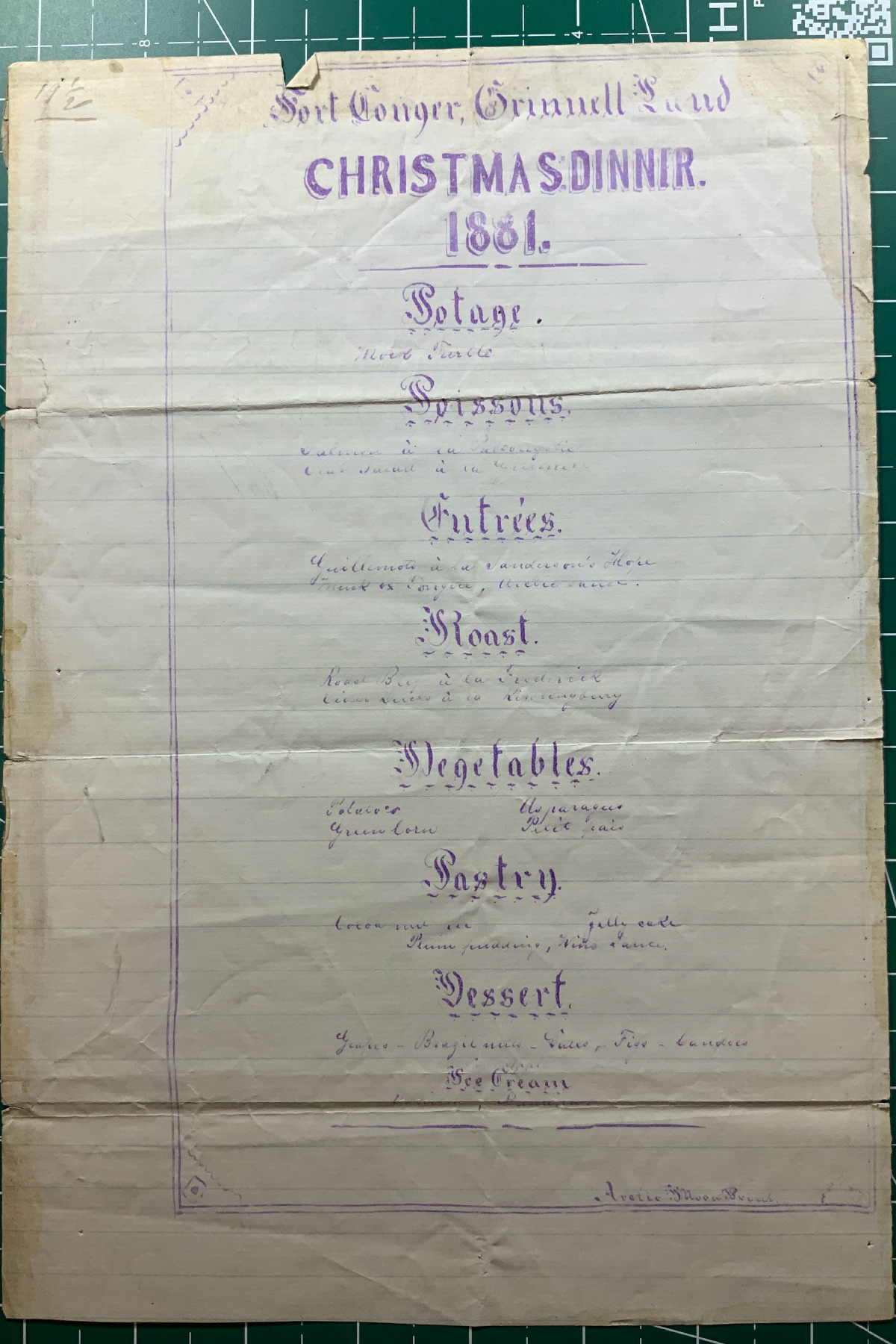

Preparations for the Christmas feast began days before the twenty-fifth. As the cooks labored in the kitchen, clanking pans and using all the burners, oven ranges, and hot water boilers, officers took the lead in decorating, hanging military standards (guidons) and other flags, as well as any and all colorful cloth that could be hung or draped festively.

The menu—given their unique status as the most northerly inhabitants in the world—was a wonder and a delight, consisting of eight courses and including the following concoctions: “Mock-turtle soup, salmon, fricasseed guillemot, spiced musk-ox tongue, crab-salad, roast beef, eider-ducks, tenderloin of musk-ox, potatoes, asparagus, green corn, green peas, cocoanut-pie, jelly-cake, plum-pudding with wine-sauce, several kinds of ice-cream, grapes, cherries, pineapples, dates, figs, nuts, candies, coffee, chocolate.” Mrs. Greely had sent along a case of her plum pudding. It was served generously with a wine sauce and was a resounding success, in part because it was accompanied by cigars as well as candies and chocolates from Huyler’s, the most famous confectioner in New York City.

The warmth and levity inside the fort were juxtaposed with the stark danger of the world just outside the walls of their sturdy shelter. During the month of December, the mean temperature was minus 32-degrees, with a low of minus 52-degrees. As they rubbed their bellies, bloated from the lavish multi-course meal, the men had no way of knowing that soon, they would all be clinging for their lives on an iceberg floating aimlessly in the sea, their rations reduced to a few ounces per man per day. But for now, the men feasted on dessert “seconds,” huffed on their cigars, swilled their Sauterne and rum drinks, and thought contentedly of home.

Adapted from Buddy Levy’s Labyrinth of Ice: The Triumphant and Tragic Greely Expedition (published by St. Martin’s Press).

* At the time, though scurvy was known as a dietary deficiency, it was not completely understood. It was known that citrus fruits like lemons and limes appeared to combat the disease, so mariners began taking them on extended voyages (resulting in the origin of British expression “Limeys”). It was not until the 1930s that the Hungarian-born Albert Szent-Györgyi isolated vitamin C, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com