No one had a well-defined plan to send microfilm specialists to war when Franklin Roosevelt agreed to established the Interdepartmental Committee for the Acquisition of Foreign Publications (IDC). The agency initially struggled to gain traction. yet over the course of the war, the IDC developed an extensive operation to provide printed sources for intelligence purposes. As bookmen and women became intelligence agents, the ordinary activities of librarianship—acquisition, cataloguing, and reproduction—became fraught with mystery, uncertainty, and even danger.

By late spring 1942, plans were set in motion to send microfilm men—and one woman—to Stockholm, Lisbon, and other neutral cities. For those in the intelligence business, wartime Lisbon was an exhilarating place to be. Dictator António de Oliveira Salazar had declared Portugal’s neutrality, hoping to avoid invasion and keep what was left of its shrunken empire. Sympathetic to fascism but bound by a long-standing treaty with Great Britain, he tacked between the Allies and the Axis. Portugal’s neutrality made it the crossroads of Europe and the Americas, a magnet for exiles, diplomats, foreign correspondents, and adventurers. Refugees from occupied countries crowded into Lisbon, enduring long waits for exit visas to England or the Western hemisphere. Cafés, newsstands, and bookstores bustled with newcomers; extravagant parties, dancing salons, and casinos beckoned the wealthy nightly. Not by chance had the city become the travel destination of spies. As one intelligence agent put it, “Lisbon is something like New York on a miniature scale with many visiting firemen passing through every few days.” The classic possibilities of urban modernity—anonymity, disguise, the refashioning of identity—were all heightened in wartime Lisbon. Business cards of oil magnates, movie moguls, and consular attachés concealed clandestine lives. Even book buyers might be intelligence agents.

Lisbon had developed its own information economy—an underground market where gossip was traded and rumor bid up. German, British, American and Japanese agents mingled, listening for intelligence and spreading disinformation. Hearsay was already common currency in a place where press censorship and the secret police prevailed, and the war in Europe stoked the rumor mills. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) even sent a memo to its station head in Lisbon about rumormongering, in the upbeat tones of a marketing expert: “In case you have never dabbled in it, the ideal way to spread a rumor is not to tell it in as many places as possible, but to put it in the bonnet of one person whom you know to be a gossip.” Agents could also make up their own rumors, as wild as they pleased, except for three forbidden subjects—future military plans, the activities of neutral countries, and the Pope.

In this world, Americans were innocents abroad, inexperienced at gathering information and assessing its plausibility and utility, outmatched by the veteran British and German clandestine operations. The first OSS agents lacked training, had no background in military or political affairs, and spoke no Portuguese. In early 1942, one admitted, “No one here, I believe, can help but feel that we are ‘behind the eight ball.’”

Into the hothouse of Lisbon came those in search of a different kind of information, in the form of the printed word. Salazar’s heavy hand did not prevent a brisk business in books, newspapers, and magazines among the polyglot population of the city. Newsstands hawked everything from the Daily Express to Das Reich, papers from “every major country in Europe except Russia.” The city had many booksellers, from the venerable Livraria Bertrand, dating to the 18th century, to the newly opened Livraria Portugal, whose owners were sympathetic to the Allied cause. Even stationery stores carried useful works: the Papelaria Fernandes specialized in military subjects, while the Papelaria Pimentel & Casquilho sold engineering books and instruments. Although hamstrung by the censors, customs restrictions and the shifting political winds, these dealers found ways to import publications and keep their shelves stocked. Lisbon hungered for books and news, and educated Portuguese and travelers alike haunted these places.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Among them were American librarians working for the IDC. They presented themselves to the Portuguese as American officials collecting materials for the Library of Congress and other governmental libraries, “which are naturally interested in preserving the records of the present crisis in our civilization.” They openly made the rounds of bookstores and stationery shops and placed subscriptions with news dealers. Sympathetic locals, including scholars, publishers, journalists and diplomats, also helped, ordering books and newspapers in their own names, as a front for the Americans. The Portuguese did not request money but desired current books and American magazines like LIFE and TIME. The IDC men would have agreed with an American secret agent who commented, “Some of my most valuable acquaintances in Lisbon have been due to my ability to furnish them with written material otherwise unavailable because of Portuguese censorship.”

By 1943 the operation was in full gear. “The publications are rolling in,” Ralph Carruthers, an IDC agent in Lisbon, exulted. “We no sooner begin to see daylight when something else comes along.” The sources and flow of publications varied with the war’s movements. When the Germans tightened border controls and sources in Switzerland began to shut down, the IDC quickly arranged for a large shipment from a Swiss bookseller to a decoy commercial address in Lisbon. The growing French and Italian resistance spurred the collection of underground publications. The IDC outpost tried to fill urgent requests from Washington war agencies, local embassy staff and agents outside Lisbon. IDC head Frederick G. Kilgour wired for Hungarian newspapers, railroad directories and prewar Baedekers to aid in military planning. One cable stressed the “great demand for about 250 original daily newspaper issues including duplicates to be obtained with utmost speed.” During Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, the OSS outpost in Algiers called on Carruthers to send current German newspapers. “It is not likely that we will get them all,” he reported, “we will be lucky if we get four out of the lot.” In fact, he managed to obtain ten papers by a circuitous route through Tangier that took four days.

What was the value of these acquisitions? In the shadow world of intelligence, the printed word was clarifying, or so it seemed. The materiality of publications made them measurable—number of books shipped and microfilm reels shot. Scientific periodicals, technical manuals and industrial directories directly from Axis and occupied countries were studied closely for evidence of enemy troop strength, new weaponry, and economic production. Even trivial items could prove meaningful: society pages might reveal the location of a regiment, and gossip columns “provide clues to scandals which a secret agent could exploit.” The disposition among the well-educated to favor printed over spoken words made such sources seem more reliable. In Lisbon, with its rich diet of rumor and speculation, OSS chief H. Gregory Thomas relished the Legation’s press digests and observed, “many leads I find can be derived here from the local press which I of course read daily.” Even the clandestine Secret Intelligence Branch, which sought human informants, found that “intelligence material from the foreign newspapers is of great value.” War agencies in Washington also considered these materials useful. But there was more to this perception than the simple act of reading texts. The librarians of the IDC transformed the familiar forms of books and serials into the genre of intelligence.

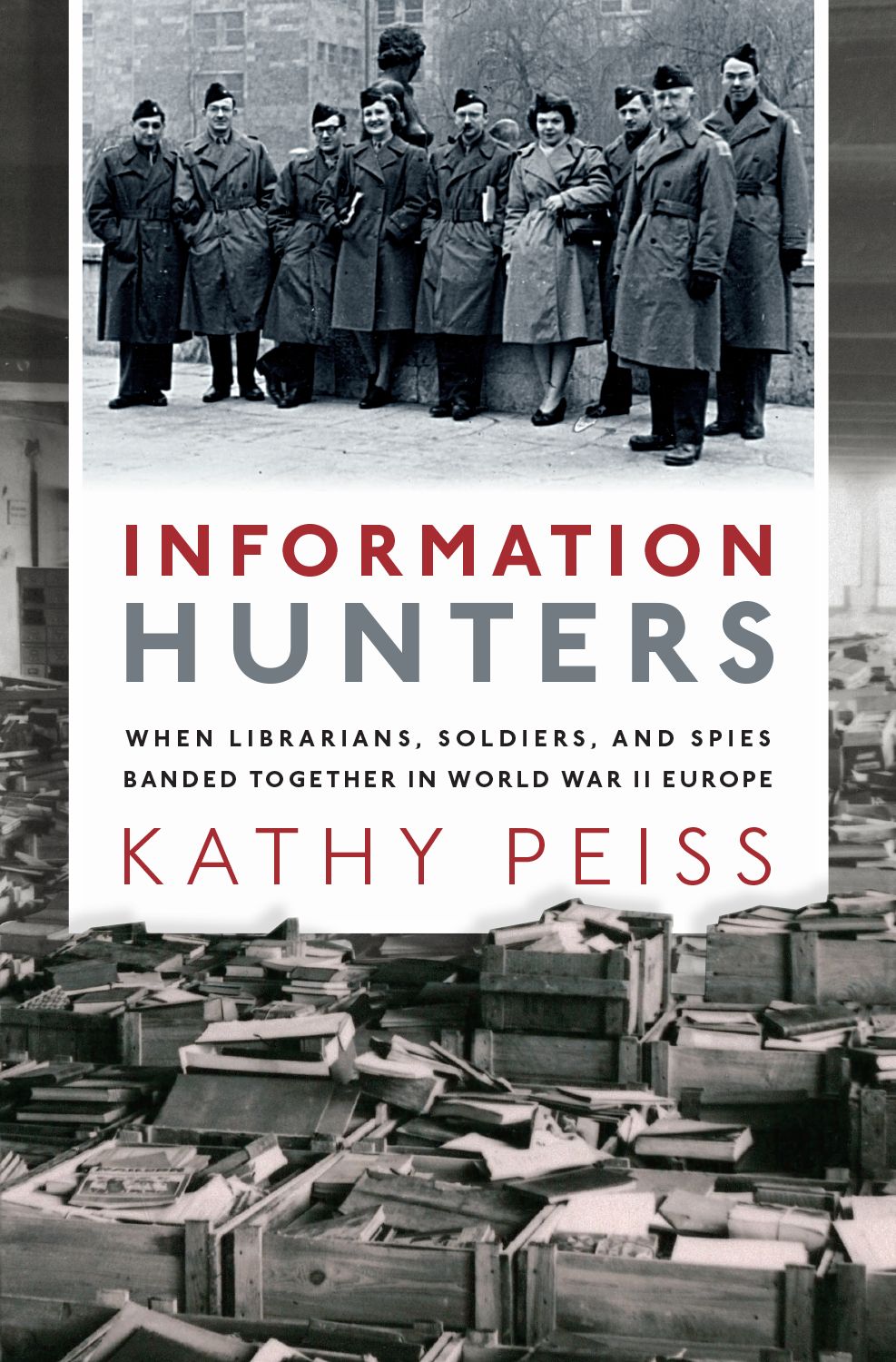

Adapted from Information Hunters: When Librarians, Soldiers, and Spies Banded Together in World War II Europe by Kathy Peiss with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2020 by Oxford University Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com