Early in his presidency, in mid-April 2017, Donald Trump and his top national-security officials gathered in the Oval Office for a briefing on North Korea. Trump sat behind his massive Resolute desk as officials crowded in around him. The briefing consisted largely of highly classified images of North Korea’s nuclear facilities and military sites. The briefers knew Trump was more a visual learner than a briefing-book kind of guy, so the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency had made a three-dimensional model of a secret North Korean facility that they brought to the Oval Office.

Trump was also shown a well-known satellite image of North Korea at night. On North Korea’s northern border was China awash in pinpricks of light, while to the south was South Korea also all lit up at night. Between China and South Korea was an almost entirely dark North Korea with only a tiny, faint light emanating from its capital, Pyongyang. The image eloquently told the story of the almost total failure of the North Korean economy.

Trump focused on the image of South Korea and its capital, Seoul. The distance from the North Korean border to Seoul was only 15 miles.

Trump remarked, “Why is Seoul so close to the North Korean border?”

The President had been regularly briefed that North Korea possessed vast artillery batteries that, in the event of war, could kill millions in Seoul. The photo seemed to bring the briefings home.

“They have to move,” he said, referring to the inhabitants of Seoul.

The officials in the Oval Office weren’t sure if Trump was joking. Trump repeated, “They have to move!” Seoul, with a population of 10 million, has roughly as many residents as Sweden. Was the President seriously suggesting 10 million people needed to leave their homes in Seoul and move elsewhere? No one knew what to say.

In this previously unreported episode, Trump demonstrated what his supporters admired so much about him: his unorthodox thinking. To his critics this was the kind of idea that underlined just how ignorant and impetuous the President was.

Trump is the first American President not to have previously served in public office or in uniform, so when he first assumed the presidency he needed the cover of senior officers around him with plenty of fruit salad (as medals are jokingly called) on their chests. No modern President has appointed so many generals to Cabinet posts: retired general Jim Mattis as Secretary of Defense, retired general John Kelly first as Secretary of Homeland Security and later as chief of staff, and retired Army lieut. general Michael Flynn as National Security Adviser, who was then replaced in that role by Lieut. General H.R. McMaster.

At first Trump reveled in the generals on his team, especially the “killers.” Trump respected the raw power embodied by the U.S. military, and he needed Cabinet officials around him who understood how the levers of national-security power actually worked and who had experience in America’s long-running wars on terrorism.

In the beginning Trump’s alliance with the generals worked well, and they guided him to some sensible decisions. Trump’s first inclination was to pull out all the American troops in Afghanistan, but the generals led by McMaster made the case that a precipitous withdrawal would create a vacuum that terrorist groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS would exploit. In August 2017 Trump announced an open-ended commitment to Afghanistan as well as a small surge of troops in order to combat the resurgent Taliban.

For a year and a half until May 2018, the generals–along with another member of the so-called axis of adults, then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson–were able to persuade Trump not to scrap the Iran nuclear deal. The International Atomic Energy Agency had repeatedly certified that Iran was sticking to the agreement and wasn’t developing nuclear weapons. Mattis wanted to stay in the Iran deal not only because it was working but also because it had been negotiated by the U.S. together with close American allies–the British, French and Germans. In Mattis’ view, if the U.S. had made an agreement, you should stick to it. Otherwise, you risked eroding what America’s word meant. Mattis lost that fight when Trump announced that he was pulling out of the nuclear deal.

Even on Russia, despite Trump’s repeated kowtowing to Russian President Vladimir Putin, Trump’s Administration actually followed a tough line at times–when, for instance, the U.S. expelled 60 Russian diplomats in March 2018 after Russian intelligence’s attempt to assassinate a former Russian spy in the United Kingdom using a nerve agent.

But Trump’s romance with his generals eventually turned disastrously sour. The differences between Trump and U.S. military leaders were partly stylistic: Trump’s lack of decorum and rudeness are certainly at odds with the military’s honor-based values. But the differences were also about policy; Pentagon officials want to sustain overseas military commitments, which they see as vital to securing world order, whether that is to defeat ISIS, contain a nuclear-armed North Korea or prevent Afghanistan from reverting to control by the Taliban. Trump believes that he was elected to end foreign entanglements and that alliances like NATO are financially ripping off the U.S. The generals knew that NATO allies had fought shoulder to shoulder with them in Afghanistan following the 9/11 attacks.

Trump fixated on getting close NATO allies like Germany to “pay up” even when they didn’t owe any money. He found it particularly irksome that while the Germans had the second largest economy in the alliance, they ponied up only around 1% of their GDP on defense while the U.S. spent around 4%. On March 17, 2017, German Chancellor Angela Merkel arrived in Washington on her first official visit to President Trump. Trump interpreted the Germans’ underspending on defense as if he were a landlord collecting overdue rent, which drove the Germans nuts. Trump’s staff produced a chart showing that Germany was purportedly $600 billion in arrears. Trump waved the “invoice” at Merkel, who told Trump, “Don’t you understand this is not real?” This was the kind of performance by the President that the generals found deeply puzzling.

And then there was the manner in which Trump conducted himself personally. In an astonishing display of insensitivity, during a 2017 meeting about how to best prosecute the Afghan war, Trump said in Kelly’s presence that the young American soldiers who had died in Afghanistan had died for a worthless cause. Trump said, “We got our boys who are over there being blown up every day for what? For nothing. Guys are dying for nothing. There’s nothing worth dying for in that country.” Kelly had lost a son in Afghanistan, 29-year-old Marine First Lieutenant Robert Kelly. Trump either didn’t know or didn’t care.

Trump set records for the level of turnover at the White House and in his Cabinet. Flynn was fired within a month of Trump’s assuming office for lying to Vice President Mike Pence. McMaster, who never really connected with Trump, was pushed out after just over a year as National Security Adviser. Kelly left when he was no longer on speaking terms with the President, which made his job as chief of staff untenable. Mattis resigned after two years because of Trump’s cavalier treatment of American allies.

Trump’s split with Mattis was a long time coming; they had fundamental policy differences that began to add up over time. The Saudi-led blockade of neighboring Qatar in June 2017 was one of the first. As the former Central Command commander, Mattis knew that in many ways the most important American base overseas was Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar, as this was where the wars against ISIS and the Taliban were coordinated. Yet initially Trump heartily endorsed the blockade because of his close alignment with the Saudis.

White House officials became increasingly frustrated with what they believed to be Mattis’ efforts not to provide a range of military options to the President, in particular for any kind of potential showdown with Iran. When it came to Iran, Mattis simply ignored the President’s directive to develop military options.

Similarly, when Vice President Pence and McMaster planned for a war game at Camp David in the fall of 2017 so they could better understand the military options the U.S. had in North Korea, Mattis never sent any military planners for the war game and so the session never happened, an episode recounted here for the first time.

Mattis believed that at any moment the President could do something irrational, so he had to be the force for reason. Mattis often said, “We have to make sure reason trumps impulse.” White House officials realized that Mattis believed Trump was a loose cannon and didn’t want to enable any bad decisions by providing military options that Trump could seize upon. White House officials started to refer to “Mad Dog” Mattis as “Little Baby Kitten” Mattis.

By the end of 2018 the axis of adults–Kelly, Mattis, McMaster and Tillerson–had all departed. Kelly saw his tenure in the White House as best measured by what he had prevented Trump from doing–for instance, pulling out of Afghanistan, as was the President’s first instinct; withdrawing from NATO; or pulling American forces out of South Korea, according to an interview he gave the Los Angeles Times.

Trump could change his mind on a dime about any issue, something more likely to happen after the departures of the axis of adults. This was demonstrated by his abrupt decision to pull U.S. forces out of Syria in December 2018. Trump changed his mind on Syria, opting to leave a residual force there, then changed his mind again, announcing a total withdrawal in October. He then re-reversed himself by leaving several hundred soldiers in Syria. On Iran, he whipsawed between offering talks with the Iranian regime and authorizing a military strike against Iranian military targets, which he then called off.

The consistent inconsistency left both allies and enemies puzzled about his intentions. If geopolitics were as relatively simple as a Manhattan real estate deal, a whiplash strategy might have been effective. Instead, over time, America’s enemies such as the Iranians, North Koreans and Russians pegged Trump as an inconsistent bully whose bark was far worse than his bite, and adjusted their policies accordingly. North Korea started testing ballistic missiles again and continued nuclear-weapons production, while Iran started enriching uranium beyond the limits of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, and Russia persisted in its large-scale information operations against the U.S.

With the departures of the generals, the world got to see Trump increasingly unplugged. Meetings between Trump and Kim Jong Un in Vietnam and at the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea yielded no tangible results. Newly imposed sanctions on the Iranians certainly had begun to bite, but Iran also restarted its uranium-enrichment program. The Trump Administration announced a partial withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan and conducted peace talks with the Taliban with no input from the Afghan government. But then, on Sept. 7, 2019, Trump surprised even his close advisers with a tweet that “the major Taliban leaders and, separately, the President of Afghanistan, were going to secretly meet with me at Camp David on Sunday.” Trump wrote that he had “cancelled the meeting and called off peace negotiations,” because the Taliban had “admitted to an attack in Kabul that killed one of our great soldiers.” The Afghan war grinds on with the Taliban more empowered and the Afghan government weaker.

Trump was now surrounded with yes-men and was running his Cabinet as he had run his real estate company, as a one-man show. The danger of having Trump surrounded by a team of acolytes was underscored by what became potentially the greatest threat to his presidency–the call he made on July 25, 2019, to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, when Trump asked the Ukrainians to investigate Joe Biden as well as his son Hunter. Kelly says he warned Trump during his final days as his chief of staff not to hire a “yes-man” to replace him, saying he risked being impeached if he did.

The generals who had once guided his national-security policies were all now long gone from his Administration. What remained was a chief executive who thrilled to the ceremonial aspects of being Commander in Chief but was generally reluctant to send American forces into harm’s way, inconsistent in his strategy and given to second-guessing the military (as he did in issuing pardons to convicted soldiers). What still isn’t clear is how the mercurial President might react to a genuine crisis.

Trump did score a real win in October when he authorized the operation in Syria in which the leader of ISIS, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, died. There were significant risks, because U.S. Special Operation forces deployed for the operation had to fly across “denied” Syrian airspace controlled by the Russians, who have sophisticated air-defense capabilities. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Mark Milley, called his Russian counterpart to warn him that the U.S. would be conducting an operation in his airspace. After al-Baghdadi blew himself up with a suicide vest, Trump held a press conference saying the ISIS leader had “died like a dog.” Trump used these words deliberately as a message to young men who might be contemplating joining ISIS. He told his advisers, “I don’t need people to walk back what I said.”

The teenager who had reveled in his time at the New York Military Academy boarding school– “I felt like I was in the military in a true sense”–was now finally his own general.

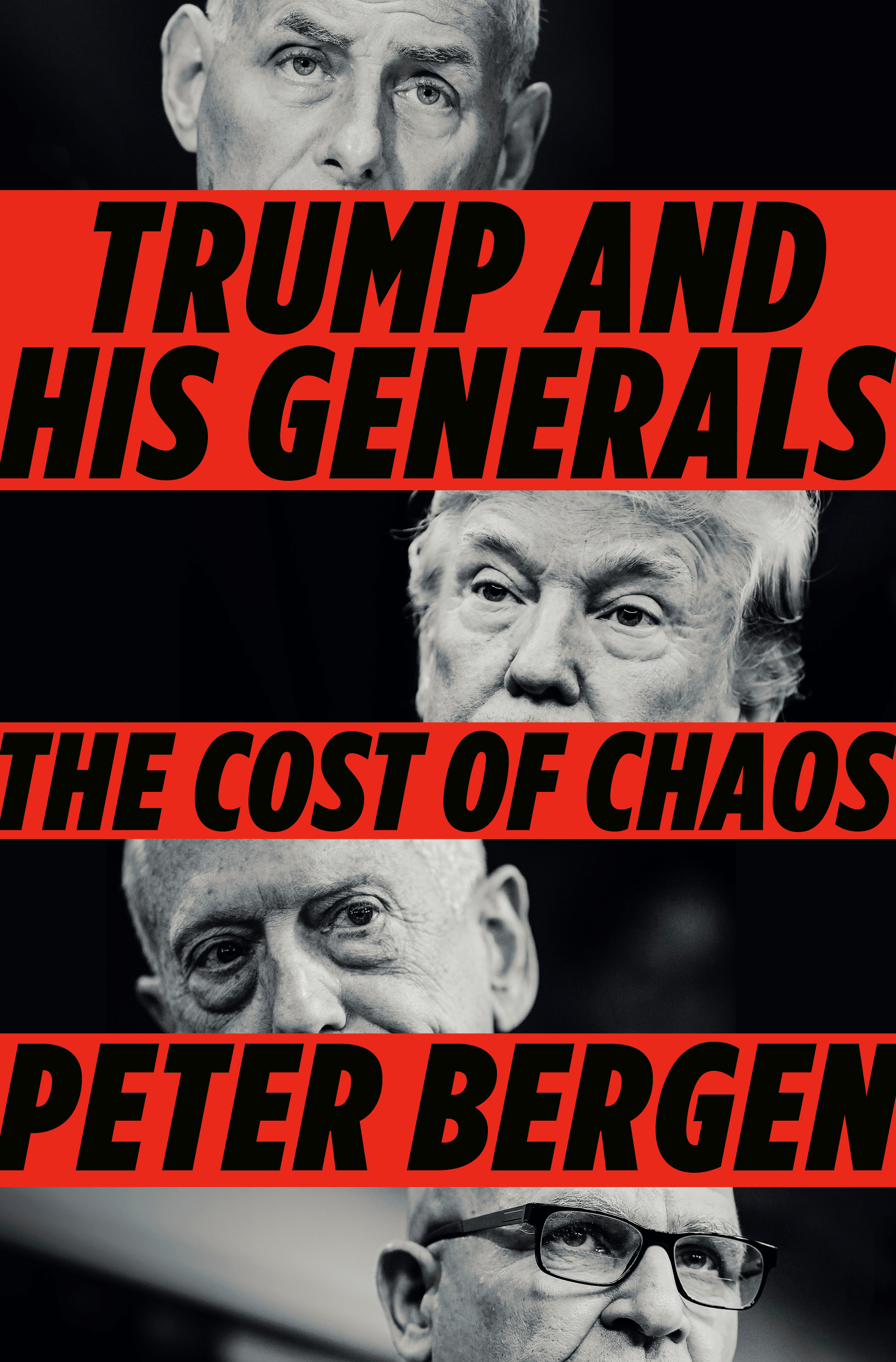

Bergen is a CNN analyst. His new book, Trump and His Generals: The Cost of Chaos, from which this article is adapted, will be published by Penguin Press on Dec. 10

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com