As the measles virus continues to spread worldwide, Samoan Prime Minister Tuilaepa Lupesoliai Sailele Malielegaoi announced Monday that Samoa will take the dramatic step of closing its government for two days this week to assist with a public vaccination campaign.

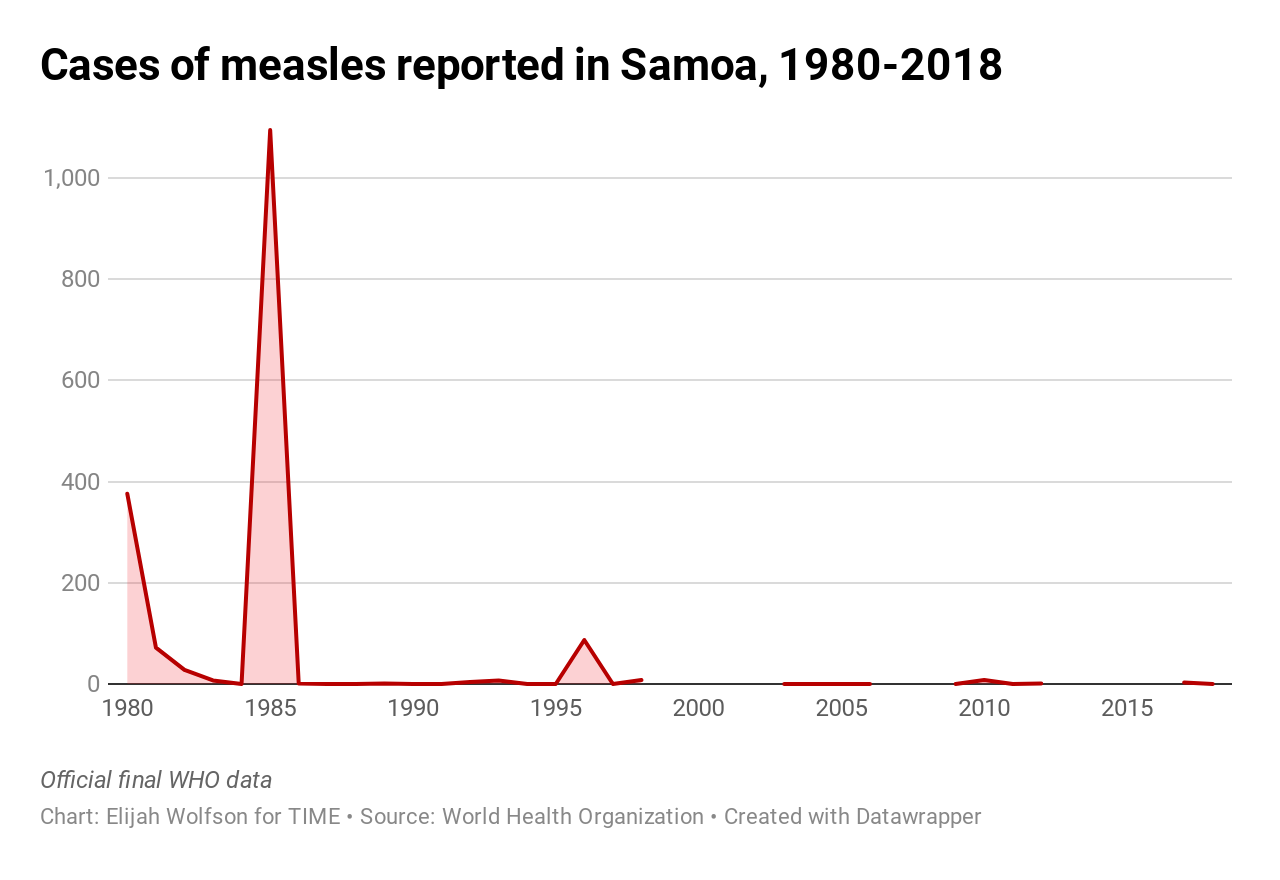

Aside from 2019, Samoa has reported almost no cases of measles to the World Health Organization (WHO) in recent years. But vaccine coverage in the small nation is lacking, partially attributable to public concern following two vaccine-related deaths that occurred in 2018 due to faulty formulas, the WHO reports. As of 2018, only 31% of children had received one of two doses of the measles vaccine, allowing the virus to spread rapidly. A total of 3,728 people, nearly 2% of Samoa’s population, have contracted measles during the current outbreak, including nearly 200 in the past day alone, according to a government statement on Dec. 1. Fifty-three people have died from measles, and the outbreak was declared an emergency on Nov. 15.

To help slow that rapid spread, all schools have been indefinitely closed since Nov. 17, and children have been barred from public gatherings. The country is also coordinating a mass vaccination campaign, with the help of about $72,000 in aid funding from the Red Cross’ Asia Pacific chapter. All government employees, except those who work in water or electric supply, will help orchestrate the campaign on Dec. 5 and 6, CNN reports. More than 58,000 Samoan people have already been vaccinated.

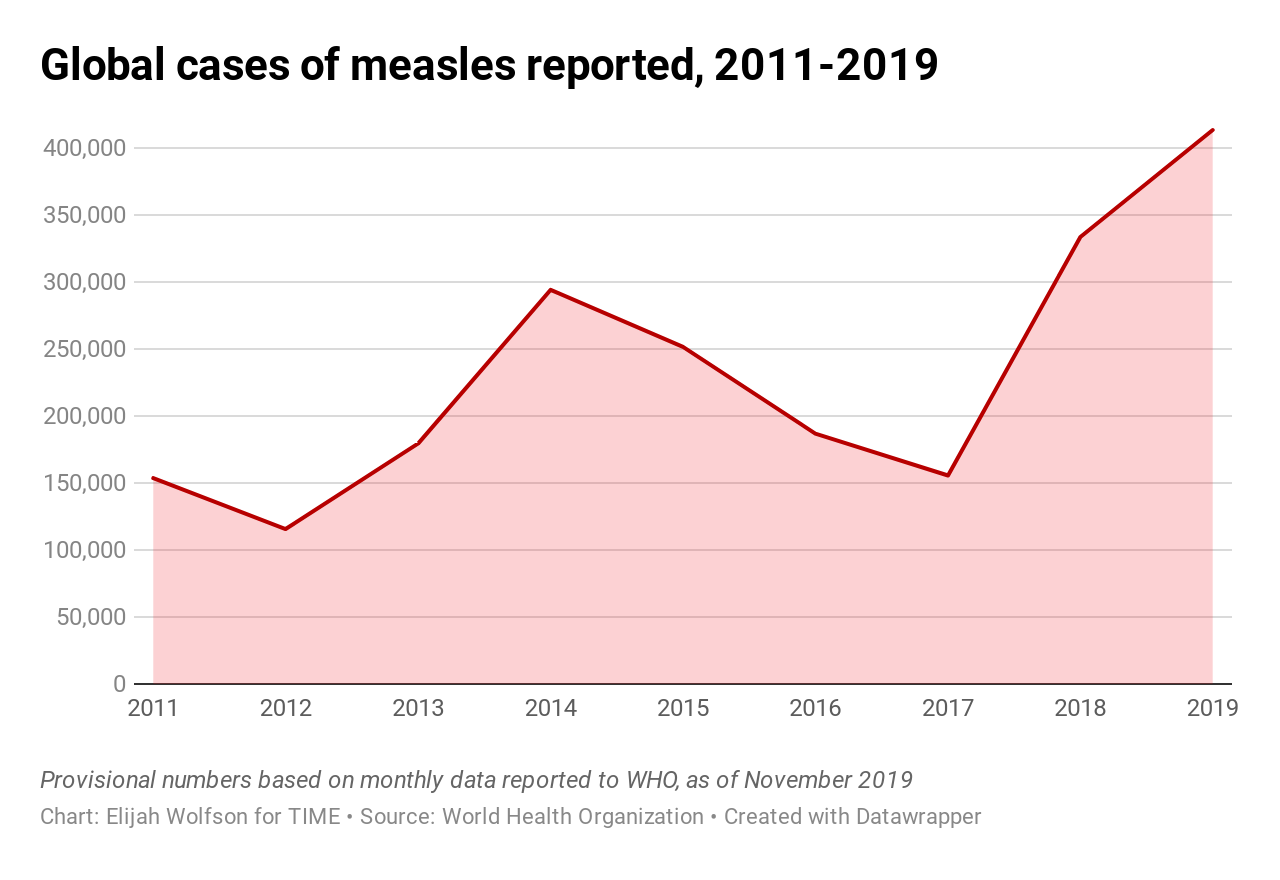

While the measles outbreak in Samoa is particularly dramatic, countries around the globe are experiencing a resurgence of the virus, which starts with minor symptoms like a runny nose and skin rash but can progress to include complications such as brain damage and predispose sufferers to other infections. In 2018, about 350,000 cases of measles were reported globally, more than double the number in 2017, according to UNICEF. And according to provisional WHO data, about 413,000 cases had been reported worldwide as of November 2019.

The WHO has blamed a dangerous rise in vaccine skepticism for the uptick, saying earlier this year that vaccine hesitancy is one of the 10 largest threats to global health. Developed countries, such as the U.S. and France, seem to show the most hesitation toward vaccination, in part due to a widely discredited belief that vaccines can cause autism.

That thinking has become so pervasive in the U.S. that the country came perilously close to losing its measles elimination status this year. The disease was declared eliminated domestically in 2000, but more than 1,200 people have been diagnosed with the virus in 2019—the most in 25 years—leading to emergency declarations in places including New York City and New York’s Rockland County.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com