In person, it can be a little hard to hear Larry Page.

That’s because he has nerve damage in both vocal cords: one was paralyzed about 14 years ago, the other left with limited movement after a cold last summer. This rare condition doesn’t slow him down, though it has made his voice raspy and faint. You have to listen carefully. But it’s generally worth it.

Page, 40, is the co-founder and CEO of one of the most successful, ubiquitous and increasingly strange companies on the planet. Google is, of course, in the search business, and more important for its profitability, it is in the online-advertising business. But it’s also in the mobile-operating-system business, the Web-browser business, the free-e-mail business, the driverless-car business, the wearable-computing business, the online-map business, the renewable-energy business and the business of providing Internet access to remote areas via high-altitude balloons, among countless others. Google’s corporate strategy is one part mainstream services and one part risky long shots.

Page prefers to refer to Google’s more out-there ventures as moon shots. “I’m not proposing that we spend all of our money on those kinds of speculative things,” he says during a rare interview at the Googleplex, the company’s Mountain View, Calif., headquarters. “But we should be spending a commensurate amount with what normal types of companies spend on research and development and spend it on things that are a little more long term and a little more ambitious than people normally would. More like moon shots.” This is why Google, in Page’s words, is not a normal type of company.

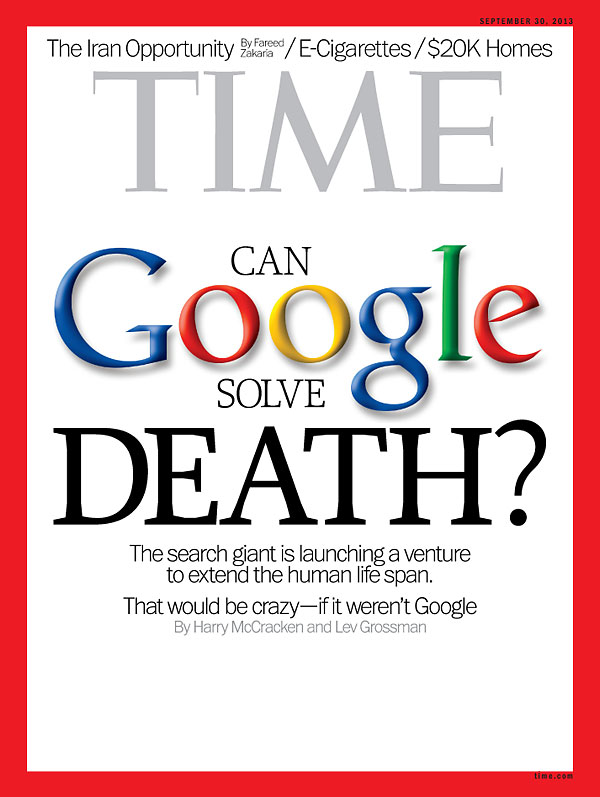

At the moment Google is working on an especially uncertain and distant shot. It is launching Calico, a new company that will focus on health and aging in particular. The independent firm will be run by Arthur Levinson, former CEO of biotech pioneer Genentech, who will also be an investor. Levinson, who began his career as a scientist and has a Ph.D. in biochemistry, plans to remain in his current roles as the chairman of the board of directors for both Genentech and Apple, a position he took over after its co-founder Steve Jobs died in 2011. In other words, the company behind YouTube and Google+ is gearing up to seriously attempt to extend the human life span.

Google isn’t exactly bursting with credibility in this arena. Its personal-medical-record service, Google Health, failed to catch on. But Calico, the company says, is different. It will be making longer-term bets than most health care companies do. “In some industries,” says Page, who spoke exclusively with TIME about the new venture, “it takes 10 or 20 years to go from an idea to something being real. Health care is certainly one of those areas. We should shoot for the things that are really, really important, so 10 or 20 years from now we have those things done.”

It’s worth pointing out that there is no other company in Silicon Valley that could plausibly make such an announcement. Smaller outfits don’t have the money; larger ones don’t have the bones. Apple may have set the standard for surprise unveilings, but excepting a major new product every few years, these mostly qualify as short term. Google’s modus operandi, in comparison, is gonzo airdrops into deep “Wait, really?” territory. Last week Apple announced a new iPhone; what did you do this week, Google? Oh, we founded a company that might one day defeat death itself.

The unavoidable question this raises is why a company built on finding information and serving ads next to it is spending untold amounts on a project that flies in the face of the basic fact of the human condition, the existential certainty of aging and death. To which the unavoidable answer is another question: Who the hell else is going to do it?

New Horizon

Google’s fondness for moon shots, and its ability to take them, can be attributed in large part to Page himself. When he was a Stanford computer-science grad student, his insight that the most relevant Web pages are those with the most links to them became the basis of a remarkably precise search engine, which he created with fellow student Sergey Brin. Google became a company in 1998 and a phenomenon shortly thereafter. Page served as its chief executive until 2001, when tech veteran Eric Schmidt was brought in from software giant Novell. Even then, the unconventional troika of Page, Brin and Schmidt raised eyebrows, but the power sharing led to Google’s monster growth years. In April 2011, Page reclaimed the CEO title, and Schmidt became executive chairman.

The effect of Page’s leadership at Google was immediately clear. In 2012 the company closed a massive $12.5 billion acquisition of troubled handset maker Motorola Mobility in a bid to begin manufacturing its own hardware. Page also reshaped Google’s management structure, creating the so-called L Team (L for Larry) of top managers. There were notable departures, including employee No. 20, Marissa Mayer, who left to run Yahoo. Most important, Page has shown that Google, long criticized as a one-trick pony dependent on serving ads, can grow its other businesses. Most of its $50 billion in revenue still comes from search-related ads. Analysts estimate that YouTube is a $4 billion business, and Android, its mobile operating system, is estimated to bring in an additional $6.8 billion from use on smartphones.

Beyond all that is the simple fact that Page is uncommonly ambitious and impatient, and he wants the company he created to be as well. “For me, it was always unsatisfying if you look at companies that get very big and they’re just doing one thing,” says Page. “Ideally, if you have more people and more resources, you can get more things solved. We’ve kind of always had that philosophy.” Longtime Google observers tend to agree. “Guys like Larry don’t focus on preserving value; they just work on building new value,” says Ben Horowitz, co-founder of venture-capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. “It’s the advantage of having made something from nothing.”

Google has never tried to solve anything quite as far afield as, well, mortality. The idea of treating aging as a disease rather than a mere fact of life is an old one–at least as a fantasy. And as a science? The American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine has been around since 1992, but the discipline it represents has yet to gain much of a foothold in mainstream medicine. Research has been slow to generate results. Consider Sirtris Pharmaceuticals, a Cambridge, Mass., company built around a promising drug called SRT501, a proprietary form of resveratrol, the substance found in red wine and once believed to have anti-aging properties. In 2008, GlaxoSmithKline snapped up Sirtris for $720 million. By 2010, with no marketable drug in sight and challenges to existing resveratrol research, GlaxoSmithKline shut down trials. Other anti-aging initiatives exist purely as nonprofits with no immediate plans for commercial products.

Why would Google be able to get traction on aging when huge pharmaceutical companies haven’t? Page himself doesn’t oversell his knowledge of the industry. “I don’t have as much personal expertise in the technology,” he admits. “I have some knowledge of it, just being in Silicon Valley.” Google has invested in gene-sequencing company 23andMe, a startup co-founded by Anne Wojcicki, Brin’s wife. And in February, Levinson and Brin joined Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner in organizing the $33 million Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences, to “recognize excellence in research aimed at curing intractable diseases and extending human life.”

It’s a lot easier to take Google’s venture seriously if you live under the invisible dome over Silicon Valley, home to a worldview whereby, broadly speaking, there is no problem that can’t be addressed by the application of liberal amounts of technology and everything is solvable if you reduce it to data and then throw enough processing power at it.

The twist is that the technophiles are right, at least up to a point. Medicine is well on its way to becoming an information science: doctors and researchers are now able to harvest and mine massive quantities of data from patients. And Google is very, very good with large data sets. While the company is holding its cards about Calico close to the vest, expect it to use its core data-handling skills to shed new light on familiar age-related maladies. Sources close to the project suggest it will start small and focus entirely on researching new technologies. When will that lead to something Google might actually sell? It’s anybody’s guess.

What’s certain is that looking at medical problems through the lens of data and statistics, rather than simply attempting to bring drugs to market, can produce startlingly counterintuitive opinions. “Are people really focused on the right things?” Page muses. “One of the things I thought was amazing is that if you solve cancer, you’d add about three years to people’s average life expectancy. We think of solving cancer as this huge thing that’ll totally change the world. But when you really take a step back and look at it, yeah, there are many, many tragic cases of cancer, and it’s very, very sad, but in the aggregate, it’s not as big an advance as you might think.” Page, in other words, is a man for whom solving–not curing–cancer may not be a big enough task.

Spring Cleaning

Page’s tenure has not been free of controversy. Like some of its competitors in Silicon Valley, Google was caught up in a government-spying scandal earlier this year. Documents leaked by Edward Snowden revealed a National Security Agency data-collection program called Prism, which internal documents claimed offered direct access to the servers of tech firms, including Google. The company denies this characterization. “There’s some misunderstanding, probably, of people assuming we were complicit,” Page says of the ongoing episode. “We’ve tried hard to correct those things. We work very hard to protect your data as a user.” In the wake of the revelations, Page and Schmidt have tried to walk a fine line, calling for greater transparency without explicitly criticizing law enforcement.

Page has also concentrated on avoiding flops like Wikipedia knockoff Knol and Google Buzz, a Twitter clone almost nobody wanted to use. He has done this, in part, by ratcheting down the number of new-product introductions and by axing existing projects in periodic “spring cleanings.” (Both of those products, for instance, were killed.) He has, in a memorable phrase, declared his intention to put “more wood behind fewer arrows.” “When Larry co-founded Google, he was not ready to run Google,” explains venture capitalist and early investor John Doerr of Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers. “Today, I can’t imagine anyone doing it better than Larry Page.” (Doerr sits on Google’s board.) Jeff Jarvis, author of What Would Google Do?, echoes that, noting that Page has been “ruthless” about nixing lackluster ideas.

The new role model for Google products turns out to be the oldest one in the store: search. Early incarnations of Google.com slaughtered competitors like AltaVista by being vastly more accurate. Other early hits like Gmail, with its abundant free storage, and Google Maps, with its Street View imagery, succeeded for similar reasons. Google is trying to prove that it can still do that. “Larry pushes us to have 10x innovations–innovation 10 times greater than what we have in the market today,” explains Johanna Wright, a vice president whose portfolio includes one of the company’s most important growth areas, mobile search.

Most of the firm’s wildest ideas are dreamed up at Google X, which functions something like Google’s fantastical subconscious. It’s a secretive research arm headquartered a three-minute ride from the main Googleplex on one of the company’s 1,000-plus brightly colored bikes. While Page tends to the entire business as CEO, Brin now devotes much of his attention to X, which he runs in partnership with scientist and entrepreneur Astro Teller. Teller’s title–just to underline the operation’s stratospheric aspirations–is “Captain of Moonshots.” (Teller changed his name from Eric to Astro, a reference to the AstroTurf-like buzz cut he sported in high school.) Except for his long hair, beard and mustache, he’s a dead ringer for his paternal grandfather, physicist Edward Teller, the father of the hydrogen bomb.

According to Teller, Google X’s moon shots have three things in common: a significant problem for the world that needs solving, a potential solution and the possibility of breakthrough technology making all the difference. (Making money comes later.) Even a proposed project that meets all these criteria probably won’t make the cut. “Sergey and I being pretty excited about it is a necessary but not sufficient condition,” Teller explains. “Depending on what it is, it might require consulting experts, it might require building prototypes, sometimes even forming a temporary team to see where it goes and then saying to the team, ‘It is your goal to kill this idea as fast as possible.'”

Four big Google X efforts are public knowledge. There’s Google Glass, the augmented-reality spectacles that pack a camera and a tiny Web-connected screen you can peek at out of the corner of your right eye and control with your voice and gestures. Makani Power–a startup that the company invested in and then bought outright in May–puts energy-generating wind turbines on flying wings that are tethered to the ground but circle 1,000 ft. in the air. Project Loon aims to deliver Internet access to remote areas of the planet by beaming it wirelessly from 39-ft.-tall helium balloons hovering 12 miles in the sky. Though Calico is a Google X–style long shot, it will be a separate entity from Teller’s shop.

But if you had to pick a Google X moon shot with the most plausible chance of permanently reshaping the way we live, it would be the self-driving automobiles. Page first became intrigued by the concept at Stanford in the mid-1990s and seems doleful that the idea was still up for grabs when Google got around to tackling it. “I think one of the big things we did is just tell people, ‘Hey, we’re going to work on it. It’s a big deal. It should be done.’ We said we’re going to actually drive on public roads and we’ll do it safely. We’re going to test it. We’re going to prove these things are possible. That all could have been done 10 years ago.”

To date, Google’s robocars, which use lasers and cameras to see other vehicles and even read road signs, have covered half a million miles of road in California, Nevada and Florida. Spotting one cruising alongside you on a Bay Area freeway–always with a human in the driver’s seat just in case–has become a common enough occurrence that it’s no longer that big a whoop. Last fall, Brin declared that the technology would be far enough along for “ordinary people” to experience it within half a decade. How Google might sell the technology was left unanswered.

Google Glass, although more fully baked, is also still in a distinctly experimental phase. Brin wears them frequently, and a few thousand people outside of Google own a $1,500 beta version. A few companies, such as Evernote and Twitter, have written apps for the device. Glass won’t go on sale in a less expensive commercial version until next year, but already the way it enables users to see information and capture images is raising concerns about privacy. (Some users report that a common question from strangers is, “Are you recording me?”) Teller says the limited release of Glass is an attempt to jump-start a conversation about the technology before it’s part of everyday life. “I think if we’re aspiring to take moon shots, designing things for today’s cultural norms, on any front, doesn’t make any sense,” he says. “You’re not going to be able to help society in a really big way if you’re fully constrained by those things. But it is also not our mind-set that we’re going to decide what the new cultural norm is.”

Unlike present-day NASA missions, Google’s moon shots are unlikely to suffer from underfunding: the company has a $54 billion cash stockpile, not to mention dominant market share in its most important lines of business. But will any of its long-shot projects be the Google cash cows of tomorrow? Maybe. Google X, says Teller, “is not a philanthropic organization.” But neither is it picking projects based on obvious profit potential. “If you make something a little bit better, people might pay you for it; they may not. But if you make the world a radically better place, the money is going to come find you, in a fair and elegant way.”

The Core

It’s not as though Google’s mainstream services–Search, YouTube, Gmail, Google Maps and Android–are languishing for lack of attention. “It’s funny, you’d think you’d run out of things to do in those core areas,” says Page. “But our core areas are so important to people: access to information, understanding the world, communications, interactions with other people, helping you with your work … It’s incredibly exciting to come in to work every day and work on those things.” Last year Google introduced Knowledge Graph, which lets its search engine understand and answer questions like “How tall is Justin Bieber?” Technologically, it represents an advance as significant as Page and Brin’s original algorithm. Last November, YouTube opened YouTube Space Los Angeles, a sprawling 41,000-sq.-ft. video-production facility housed in a rehabbed 1950 aircraft hangar originally erected by Howard Hughes. Smaller YouTube Spaces have opened in London and Tokyo, with more on the way. “Programmers like to move to Silicon Valley,” says Robert Kyncl, who heads YouTube’s content and business operations. “With creators, it’s New York, L.A., London, Mumbai, Tokyo. Those are their tribal areas. We felt like it was important for us to have our physical tent in those areas.”

Page says his primary responsibility is to make sure that the entire organization errs on the side of thinking big. “Larry always asks hard questions,” says Brian McClendon, VP of Google Geo, who joined in 2004 when the company bought his startup and renamed its 3-D-mapping program Google Earth. “Sometimes he asks unreasonably hard questions. He forces you to think, ‘Did I actually get as much out of this plan as I could have?’ He does that even when you do great things.”

Despite its founder’s emphasis on focus, Google is not immune to distractions. In August, technology site All Things D reported that Brin and Wojcicki had separated, setting off an unprecedented flurry of coverage of their personal lives. More important, even juggernauts like Apple and Amazon have learned how willing investors are to punish overly long-term bets by driving down a company’s stock price if they are displeased. So far that hasn’t been a problem: Google’s stock hit its all-time high in July at $928 a share.

Page concedes that he’s been known to underestimate how tough it all can be: “I’m very optimistic and certain about things, so I always assume they’re going to get done quickly, but actually they take a long time.” He says he initially thought Google could whip up great software for next-generation smartphones in a year but learned that getting Android there was a half-decade effort. Though it did get there: Android is closing in on an 80% share of the smartphone market.

Again, he sounds impatient. “Big companies–and maybe even Google too–we’re not as good as we should be at starting these things up early enough so that it’s really done by the time we need it to be a real business.” Though Page doesn’t mention Google+, the company’s attempt to roll an array of services into a cohesive Facebook competitor, it’s a case in point: In 2011 he tied part of every employee’s bonus to their contributions to Google’s social effort. The results, though slick, haven’t yet gelled into anything with a fraction of Facebook’s impact or revenue.

The truth about Page’s brand of 10x thinking is that it creates a never-ending cycle. If you believe that it is always possible to be 10 times better than your current self (or the other guy), it is impossible to reach a state of self-satisfaction. Which means that even if Calico, Glass, self-driving cars, Makani Power and Project Loon all turn out to be wild, epoch-shifting hits, success for Google will still be another moon shot or two away. And Page will probably be fretting that the company isn’t moving fast enough to launch them.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com