On Thursday night, Sen. Elizabeth Warren delivered a major speech about the power of black women fighters, meant to pitch herself to a key constituency in the Democratic primary. But the evening went a little differently than she’d planned. She was interrupted by black activists, defended by black allies, and ended the night doing exactly the thing that already has won her the support of many leaders in the black community: listening.

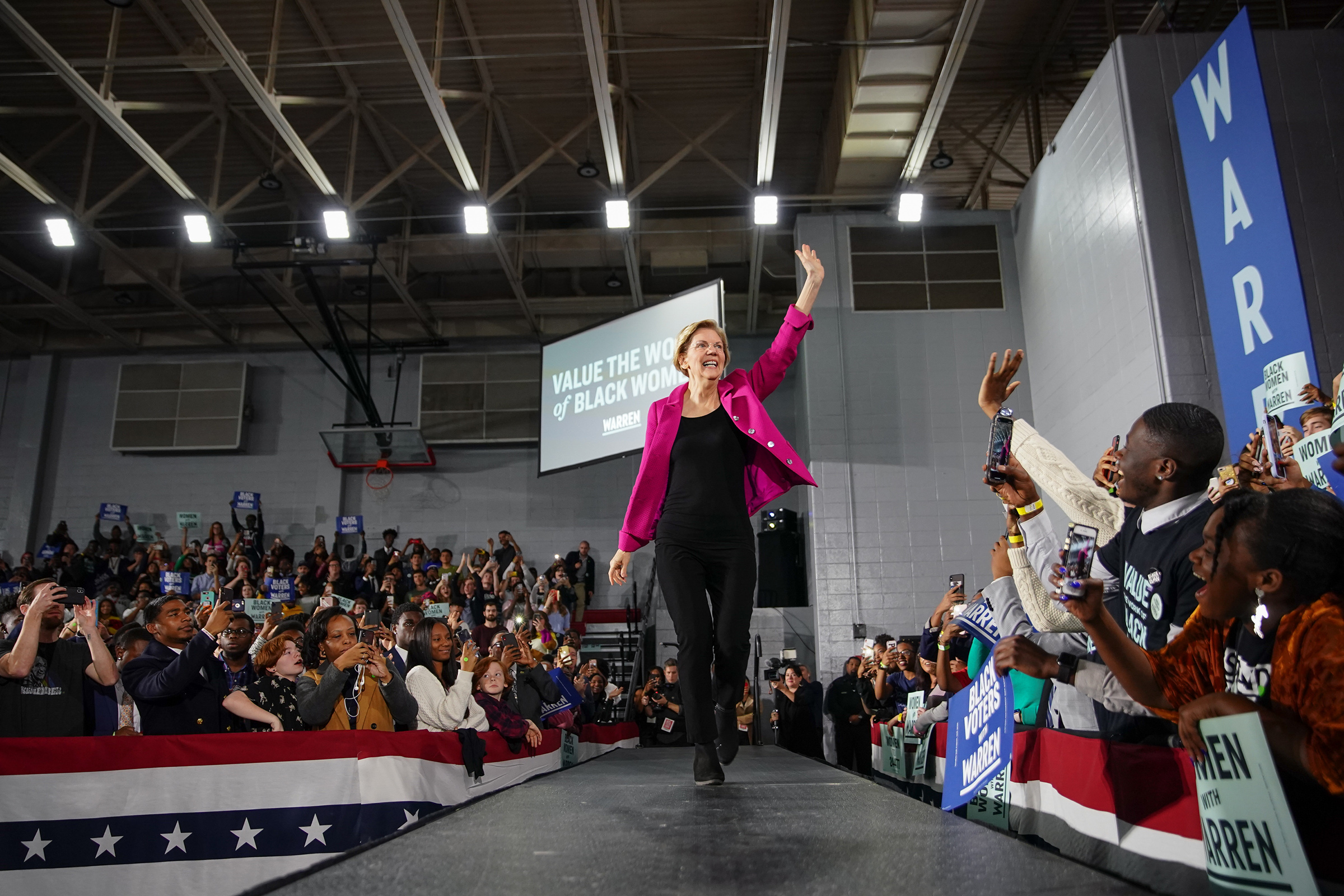

After an introduction by Rep. Ayanna Pressley, Warren approached the podium and began to talk about the Washerwomen’s Strike of 1881, the culmination of months of honing her message about racial and economic justice. Speaking to a crowd of roughly two thousand people at Clark Atlanta University, a historically black institution, Warren’s speech linked the history of black women’s movements to the fight for racial and economic justice. “The fighters I want to talk about tonight,” she said, “are Black women.”

But before the Massachusetts Senator could get going, there was a ripple in the room. A group of roughly two dozen pro-charter school activists—many of them black women who had travelled to Georgia for the occasion—began protesting Warren’s opposition to some forms of charter schools. The optics were both awkward and ironic: Warren, a white woman, poised to give speech about the disruptive power of black women activists, was being disrupted by black women activists.

Who should be TIME’s Person of the Year for 2019? Cast your vote in the reader poll.

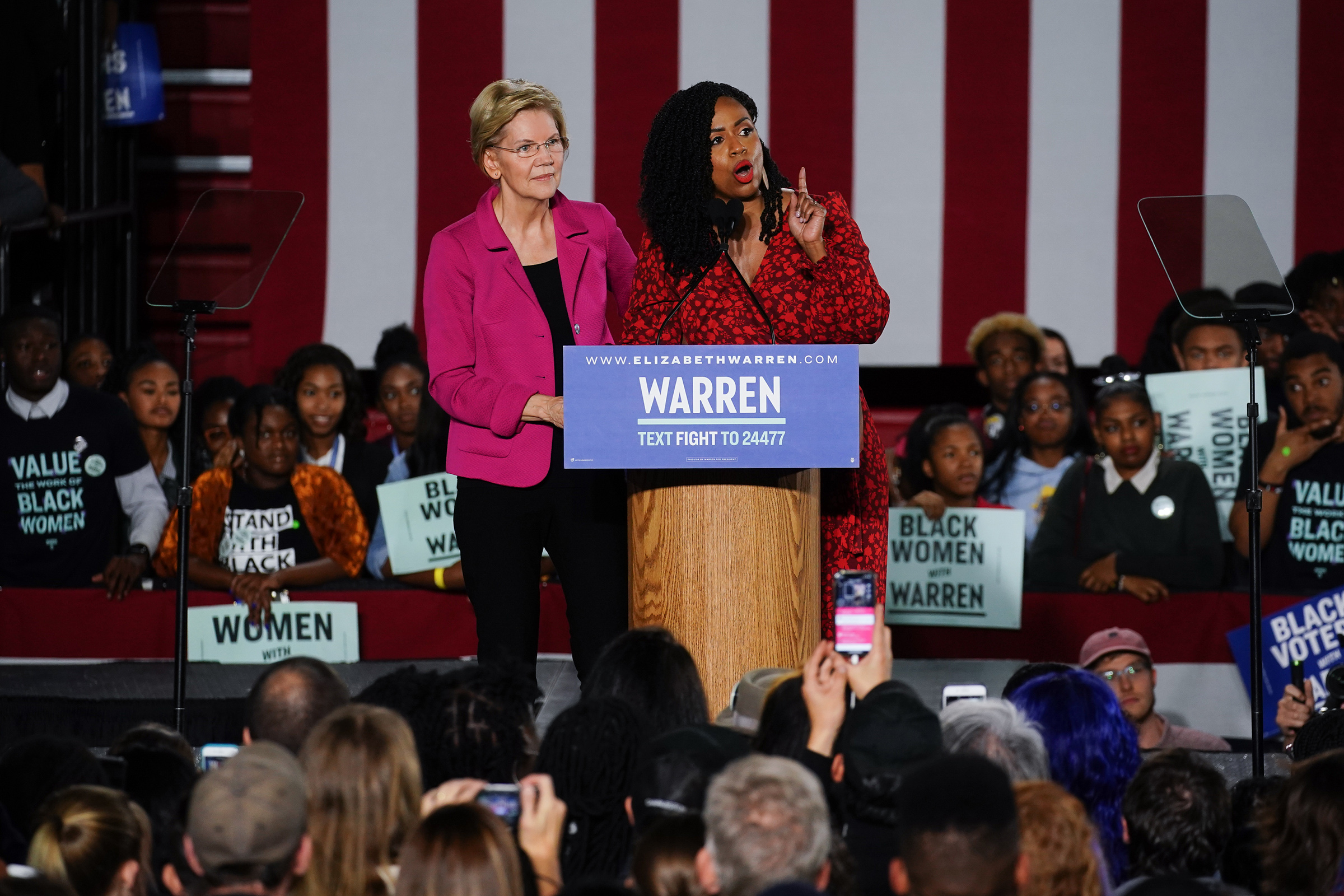

Warren paused and tried to start again, but was once again shouted down. After a few more false starts, Pressley joined her at the podium. Warren turned to her and whispered, “What do we do with this?” Pressley came to her rescue, reminding the crowd that Warren was there to celebrate the historical contributions of black women’s movements that have been long overlooked. “We are grateful for your activism and your voice and you are welcome here,” she said. “But when these women have been ignored this long, this is their moment, and we are going to hear the story.” (The Intercept’s Ryan Grim later reported that the pro-charter group was funded in part by the Walton Foundation, run by the billionaire family that runs Walmart.)

The activists were escorted out and Warren resumed her speech. But the moment underscored the strategic reason that Warren was there in the first place: black women are powerful allies and equally powerful adversaries—and no Democratic candidate can win without their support.

Warren has already assembled a formidable coalition of black women. She was recently endorsed by Black Womxn For, an organization of black women and gender nonconforming people which includes leaders in the Movement for Black Lives and close allies of Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams. Author Roxane Gay endorsed Warren last month and lent her voice to a video teaser for her speech. And Rep. Ayanna Pressley, a progressive Massachusetts congresswoman, broke with her fellow members of the Squad to endorse Warren over Sen. Bernie Sanders.

“People feel like they see her and she shows up,” says Adrianne Shropshire, executive director of BlackPAC, adding that the more black voters hear Warren, the more they like her. “Warren talks about redlining and racial disparities in our economy whether she’s in Iowa or South Carolina or New Hampshire or Alabama. That consistency can’t be underestimated.” (BlackPAC, which mobilizes black voters to support candidates who center black communities, has not endorsed a presidential candidate.)

In recent weeks, Warren has intensified her pitch to black voters, and black women in particular. The core of the Democratic party base, black women are responsible for many of the Democrats’ biggest victories over the last three years, including Senator Doug Jones’s surprise win in Alabama in 2017. While a majority of white women voted for Donald Trump, 94% of black women voted for Hillary Clinton. One NBC analysis projected that, if current trends continue, at least one in four 2020 Democratic primary voters will be black.

So Warren’s path to the Democratic nomination depends on black support, and her rhetoric and policy proposals are a reflection of that reality. Just as her campaign launch in Lawrence Massachusetts highlighted the power of striking mill workers and her major speech in Washington Square Park praised the legacy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire and reformers like Frances Perkins, the Atlanta speech celebrated the legacy of black women activists like the Washing Society in 1881 and subsequent domestic worker organizers like Dorothy Bolden. It also presented a clear link between the struggle for racial justice to Warren’s message of economic equality.

Nearly every one of Warren’s many proposed plans contains specific references to addressing racial justice. Her education plans includes a $50 billion investment in historically black colleges and universities. Her housing plan includes down payment assistance for families in areas that have been historically redlined. Her childcare plan includes raising wages for domestic care workers, who are overwhelmingly women of color. Her health care plan specifies the need to address black maternal mortality. “The federal government helped create the racial divide in this country through decades of active, state-sponsored discrimination,” Warren said in her speech. “And that means the federal government has an obligation to fix it.”

In her speech Thursday, Warren made the case that policies like voting rights and desegregation lead to a better democracy and a better education for everyone, not just black Americans. “The lesson is clear: Racism doesn’t just tear apart Black and Brown communities. It keeps all working people down,” she said. “Racism props up the wealthy and powerful, leaving them free to take more wealth and more power for themselves.”

The competition from other candidates is stiff: Biden still leads handily with black voters, boosted by high name recognition and an affiliation with Barack Obama; Sen. Kamala Harris, the only black woman currently in the U.S. Senate, has been leaning on powerful black sororities; and Sen. Bernie Sanders, who also has high name recognition from his 2016 bid, has solid support from many black progressive activists.

Yet Warren has been persistent. Black community leaders say she has been quietly building relationships for months, often by making personal phone calls or setting up private meetings without staff. Activists say she has listened closely when she’s come under criticism, stayed in touch with movement leaders, and been responsive to their demands. That’s one reason her support is growing. According to an analysis by Axios, less than 1% of black Democrats said they supported Warren in March. By late October she was polling around 20%.

Over and over, black women leaders say that they’ve been impressed by Warren’s habit of reaching out, personally and frequently, and actively listening to their concerns. Her responsiveness has caught the attention of high-profile black organizers, even in a crowded field with two black candidates. “I kept finding time and time again that the campaign that had created an on-ramp for responsiveness, for accountability and new ideas was the Warren campaign,” says Jessica Byrd, founder of Three Point Strategies and a member of Black Womxn For. Byrd, who has been a leader in the Movement for Black Lives and helped run Stacey Abrams’s 2018 governor’s bid, also organized the She the People forum in February. After the event, Byrd said, many activists told her they had gotten calls from Warren asking to open a dialogue. “They’re demonstrating that they want to get this right and they want to get all the voices around the table to get it right,” she said.

“We made asks about how we want her to govern, and how to commit to being in relationship with us,” said Angela Peoples, director of Black Womxn For. “When we made those asks, her team was enthusiastic, and thanked us.” One text chain of black women activists found themselves discussing Warren’s policies as they watched her in debates. “These women who I consider my political leaders are saying ‘what if we called them up and asked them to expand their analysis on this?” Byrd recalled. “And they’re answering the phone every time!”

Black women leaders said they were also impressed that Warren’s staff includes women of color at high-level positions in nearly every department. “I always feel heard,” said one black woman staffer. “She’s attentive to being guided, and that’s significant, and you don’t always get that from elected officials or people who are running for President.”

All those personal phone calls and private meetings culminated with the speech Thursday, in which the white woman Senator, surrounded by black women allies, delivered a simple pitch to the core constituency that may help decide the Democratic primary, implicitly linking her destiny with theirs. “I’ve been called persistent in my time—and I love it,” she said. “But understand this: The persistence of generations of black women, and black people in America, up to and including many people in this crowd tonight, is the true story of American persistence.”

And then, after the speech and the selfie line, Warren did what she has so often done: she lingered and listened. She met with the activists who had disrupted her speech and stood, mostly quietly, for more than fifteen minutes while they explained their fear that her education plan would eliminate charter school options for black students (Warren’s plan would freeze federal funding for new charter schools, ban for-profit charters and make charter schools follow the same standards as public schools.) She stood in a posture of active attention, with her left arm crossed and her right hand on her chin, occasionally nodding her head. In the end, she agreed to take another look at her own plan with their concerns in mind.

“I’m not making promises, I’ll go back and read it,” she told one activist. “I want to make sure I got it right.”

Correction, Nov. 25

The original version of this story misstated the mission of BlackPAC. They support black voter mobilization and candidates who center black communities, not exclusively black candidates.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com