Michael Bernstein weighed 155 pounds on a full belly, but at 36 he was a storied prosecutor at the Department of Justice’s Office of Special Investigations (OSI) who spent long afternoons in the records room, a lone figure hunched under the fuzzy glow of fluorescent lights, files from cold cases spread across the table.

No one was much surprised to find him there, searching for clues that may have been missed and then wandering back to his office, where he had taped an adage from a fortune cookie to the door: The law sometimes sleeps but it never dies.

At the chilly start of December 1988, Bernstein agreed to fly to Vienna on behalf of OSI. He would be home in time to celebrate Chanukah with his 7-year-old daughter and 4-year-old son.

In Austria, Bernstein would see about a matter that had been thwarting the mission of the Office of Special Investigations for years. In Bonn in 1954, the Foreign Office of West Germany had signed a critical commitment, neatly typed and bearing the coat of arms for the Federal Republic of Germany, a black eagle, wings extended wide against a golden field. The country had agreed to take back Nazi perpetrators discovered in the United States after the war. American diplomats also secured a nearly identical guarantee from neighboring Austria, which promised that Nazi criminals would be readmitted “upon demand of the American authorities.”

U.S. officials had tucked copies of the guarantees inside the immigration files of thousands of European refugees who entered the country in the mid-1950s, and no one thought much about it—a rather technical agreement between friendly nations—until the Office of Special Investigations discovered dozens of Nazi collaborators guarding ugly secrets in America’s cities and suburbs.

In the early 1980s, juggling a growing roster of OSI defendants, the department’s Eli Rosenbaum and Neal Sher had pressed the matter at the German embassy in Washington. Without countries willing to readmit Nazi perpetrators, OSI could not enforce deportation orders.

“We can’t find a copy of that guaranty in our files,” the German Consul General told Sher and Rosenbaum, frowning at the two men. Rosenbaum, fresh out of law school, watched his boss cringe.

“It’s in U.S. government immigration files,” Sher had replied sternly.

More than two hundred thousand refugees were admitted into the United States under the Refugee Relief Act of 1953, a sweeping immigration law passed by Congress to assist displaced eastern Europeans in the years after the war. Sher produced a copy of the agreement, but the German Consul General was indignant.

“My government questions its authenticity.”

The text, she pointed out, didn’t contain the umlaut, a character that appears over several vowels in the German alphabet. Rosenbaum frowned. “You can’t seriously suggest that this isn’t authentic.”

She shrugged, and Rosenbaum knew that the conversation was over. He thought of the concentration camp guards and police commanders who had committed crimes in the name of the German state and then escaped justice by fleeing to the shores of America, home to tens of thousands of Jewish survivors and the veterans who had crossed an ocean to free them. How many Nazi collaborators would get to grow old in comfort while OSI pleaded with Germany to take them back? Unlike the U.S. government, Germany possessed the legal authority to criminally prosecute Nazi perpetrators.

The Austrians had resisted, too, arguing that the readmission guarantee was nearly three decades old and no longer valid. In truth, the agreements applied only to refugees who came to the United States in the mid-1950s. Hundreds of thousands had emigrated earlier in the tumultuous postwar years when Communism was advancing across Eastern Europe.

Rosenbaum and Sher believed that Germany and Austria bore an ethical obligation to take back the criminals that the Third Reich had created, empowered, and armed, no matter when they had slipped out of Europe and crossed the Atlantic. But from its obscure outpost at the Department of Justice, under the critical eye of pundits and émigré groups, and with resistance from the diplomats who represented the United States in foreign affairs, OSI would have to find a way to remove Nazi defendants on its own.

The lack of cooperation from Germany and Austria was a significant threat, the most critical in the short history of OSI, and when the Austrian government appeared to be reconsidering its position in the final months of 1988, Rosenbaum and the staff of OSI could scarcely believe the turn of events. After years of pushback, the Austrians were willing to come to the table to talk about readmitting Nazi criminals. It was an olive branch, Rosenbaum thought, a potential step toward real cooperation.

Michael Bernstein and an official from the U.S. State Department had attended a first round of talks in Washington, but the meeting ended without an agreement. The Austrians insisted on a meeting in Vienna. Bernstein would go. He was one of the best negotiators in the office. It promised to be a plum assignment, the chance to bring home a badly needed diplomatic win for the beleaguered unit.

Finally, OSI might catch a break.

Even in the bustling offices of the Justice Department, the sound of a breaking-news bulletin, rushed and urgent, was unmistakable. Pan Am flight 103, just 38 minutes into its route from London to New York, had lost contact with air traffic controllers in the skies over Lockerbie, Scotland, and gone down in a ball of flames. There were 259 people on board. All were believed to be dead.

Eli Rosenbaum sucked in his breath. After four days in Vienna, Michael Bernstein was on his way home, a copy of the freshly signed deportation agreement tucked inside his briefcase. The Austrian government had agreed to take back its Nazi criminals, an extraordinary victory for OSI.

The details of Bernstein’s travel plans were unclear. His original flight had been canceled, and no one was entirely sure which plane he had rebooked on since multiple flights a day flew between London and New York or Washington.

Frantic, Rosenbaum started making calls. In the early-morning hours, the phone rang again. It was official: Bernstein had been on the doomed flight.

There but for the grace of God go I.

The words looped round and round in Rosenbaum’s head as he parked his car near Michael Bernstein’s house later that morning and made his way inside. He thought about his own family, the daughter who had been born only two months earlier, and wondered what he might say to Bernstein’s children, Sara and Joe.

Rosenbaum went to look for Stephanie Bernstein. She had been using her exercise bike in the basement the night before when news of the crash flashed on television. She raced to make calls and knew that her husband was dead when she was finally transferred to a phone line for relatives of passengers on the Pan Am flight.

She peeked in on her children and decided to let them sleep through the night, a few more hours without knowing, steady breaths under warm blankets, in tiny bedrooms with views of the wildflowers that bloomed every spring in the family’s backyard. She wandered to her own bedroom, past the haphazard pile of issues of the New York Review of Books that her husband stacked on the floor by the side of the bed for some time later when there would surely be time for reading. She started making phone calls.

Looking at Stephanie, a widow at 37, Rosenbaum felt sick. The Pan Am Boeing 747 jetliner, once dubbed the Clipper Morning Light, had left a wreckage that spread across one nautical mile.

He imagined Bernstein in seat 47D, heading home to his family, the signed agreement with the Austrian government in the overhead bin. Later, the world would learn that a terrorist bomb had punched a 20-inch hole on the left side of the plane’s fuselage.

Rosenbaum hugged Stephanie and wandered upstairs, where 4-year-old Joe was playing in his bedroom, oblivious to the somber gathering.

Rosenbaum would help send FBI agents to Scotland to try to persuade authorities to release Bernstein’s remains so that he could be buried quickly, according to Jewish custom. He would call the New York Times to request an obituary and ask famed Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal to write a letter of condolence to the Bernstein family. He would deliver remarks at the memorial service on behalf of the Department of Justice and recite the Mourner’s Kaddish alongside hundreds of people.

He would tell journalists that Bernstein was responsible for deporting seven of the 24 Nazi defendants that had been removed from the United States since OSI had been in operation. He would help write the Justice Department announcement, three months later, declaring that a California man who was once an armed SS guard at Auschwitz had been deported to his native Austria, thanks to the agreement that Bernstein helped negotiate.

And, for as long as he stayed at OSI, he would keep a picture of Bernstein in his office—a daily reminder of the man who had died in the line of duty more than 40 years after the war’s end.

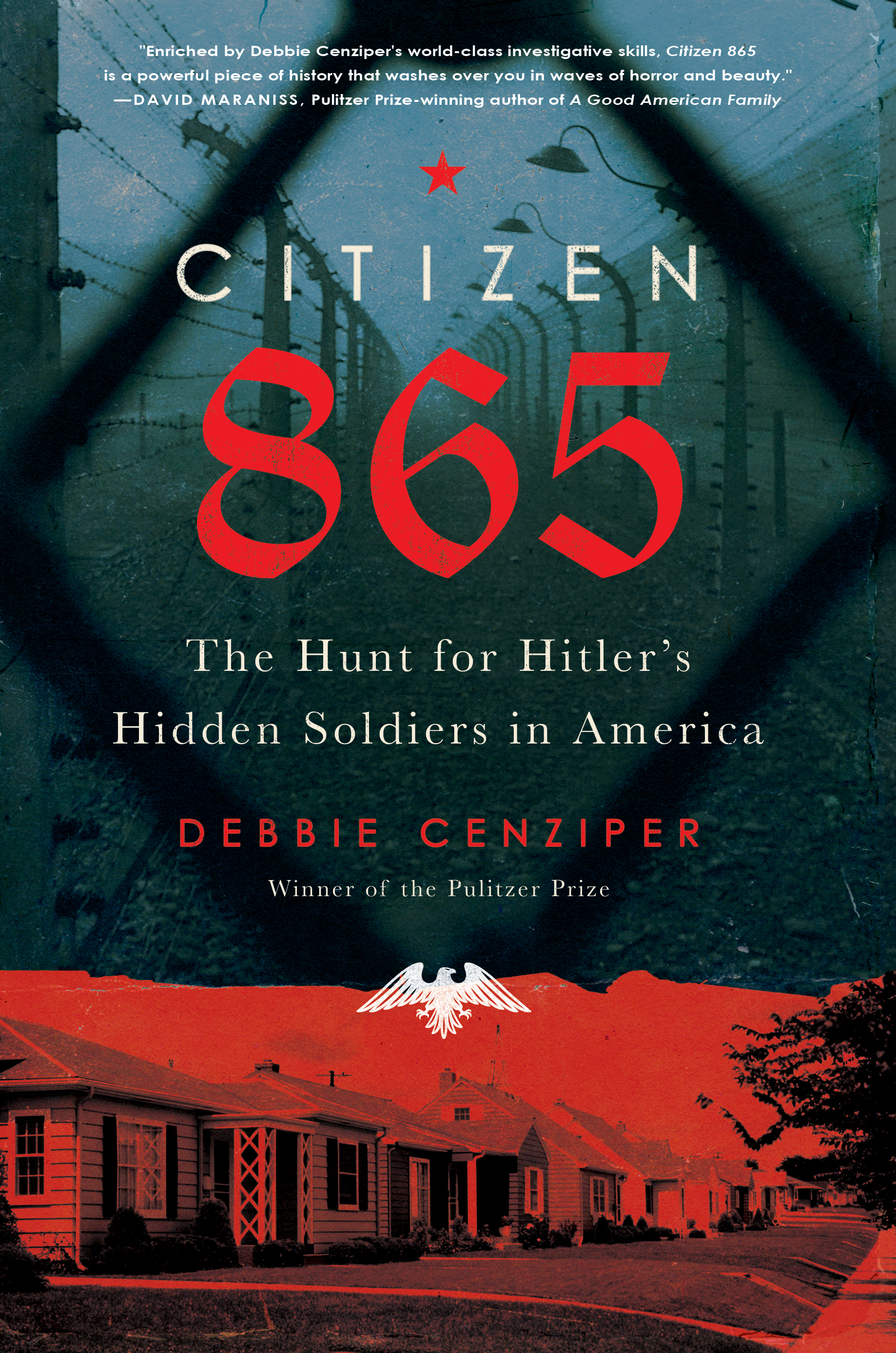

Excerpted from Citizen 865: The Hunt for Hitler’s Hidden Soldiers in America by Debbie Cenziper. Copyright © 2019. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com