We don’t think of the bento box as an important innovation, but we should. Created sometime in 12th or 13th century Japan, the bento box arguably invented food packaging as we know it today.

The secret to the bento box’s success is in its name: bento derives from a Japanese word meaning convenience. The bento’s four internal compartments and lid enable someone to easily carry a balanced meal of a variety of dishes without it getting spoiled. Ten centuries after its invention, the bento box remains one of the most balanced, healthy, and convenient meals around.

Could the bento box do the same for how we see our self-interest?

My journey to the bento began at the corner of 2nd Avenue and 1st Street in the Lower East Side. The same corner where Hank Penza ran the punk dive Mars Bar for a quarter century before being replaced by a TD Bank in 2014. The fourth TD Bank within walking distance of that corner at the time.

I lived in the neighborhood and saw it happen. It was heartbreaking — and baffling. As if a malicious real estate virus was turning storefronts into banks and cell phone stores. While property values were rising, other values — like social cohesion, traditions, and other forms of neighborhood prosperity — were declining. The neighborhood was getting worse and somehow it didn’t seem to matter. Why was one value valuable and the others not?

The answer, I came to realize, was in how we defined our self-interest.

For centuries, philosophers, economists, and social theorists have considered the question of our rational self-interest. One of them, Adam Smith, observed that it’s not from the benevolence of the butcher that we get fed but because of the butcher’s self-interest. This laid the foundation for not only capitalism, but how we define rational behavior today.

In the 1940s our belief in self-interest intensified with the creation of game theory, which uses mathematical models to determine the optimal, rational strategies in games and strategic conflicts. Game theory was developed at the RAND Corporation, where its simulations helped the Defense Department forecast what would happen in a nuclear conflict. The scientists thought this application was just the tip of the iceberg.

“We believe it possible that Game Theory, as it develops—or something like it—may become an important concept and force in many phases of life,” wrote RAND scientist J.D. Williams in a 1954 book published by the think tank, called The Compleat Strategyst.

They were right. Game theory came to define a new hyper-rational way of thinking that saw life as a series of strategic conflicts where the only rational goal was to get as much for yourself as you possibly could. The book goes on:

“The notion that there is some way people ought to behave does not refer to an obligation based on law or ethics. Rather it refers to a kind of mathematical morality, or at least frugality, which claims that the sensible object of the player is to gain as much from the game as he can, safely, in the face of a skillful opponent who is pursuing an antithetical goal. This is our model of rational behavior.”

This mind‐set guided the United States’ strategy toward the Soviet Union in the Cold War. It wasn’t long before the philosophy spread into everyday life, just as the game theorists predicted. We weren’t a society. We were each in our own cold wars. Everyone against everyone else. The only logical conclusion was to go get yours.

—

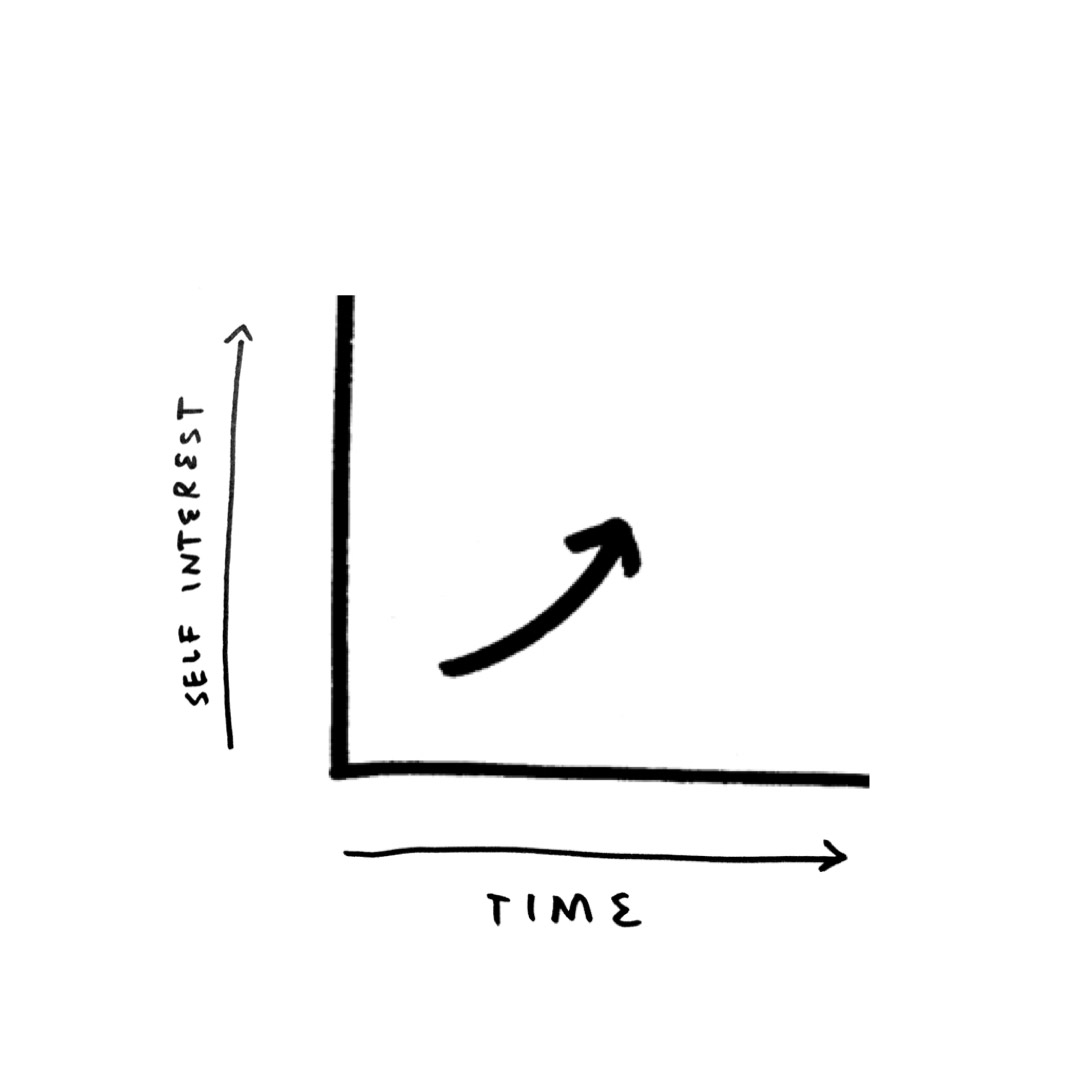

When I picture how we see self-interest today, I imagine a simple graph. On the X-axis is time. On the Y-axis is some value — money, power, units sold — that’s exponentially growing. In Silicon Valley this is called a “hockey stick” graph. In our current era of self-maximization, there’s nothing better.

But this idea of making it is just a sliver of our actual self-interest. While we so intently focus on hockey stick growth, there’s a larger universe that we miss. When we take a step back, this bigger picture starts to emerge.

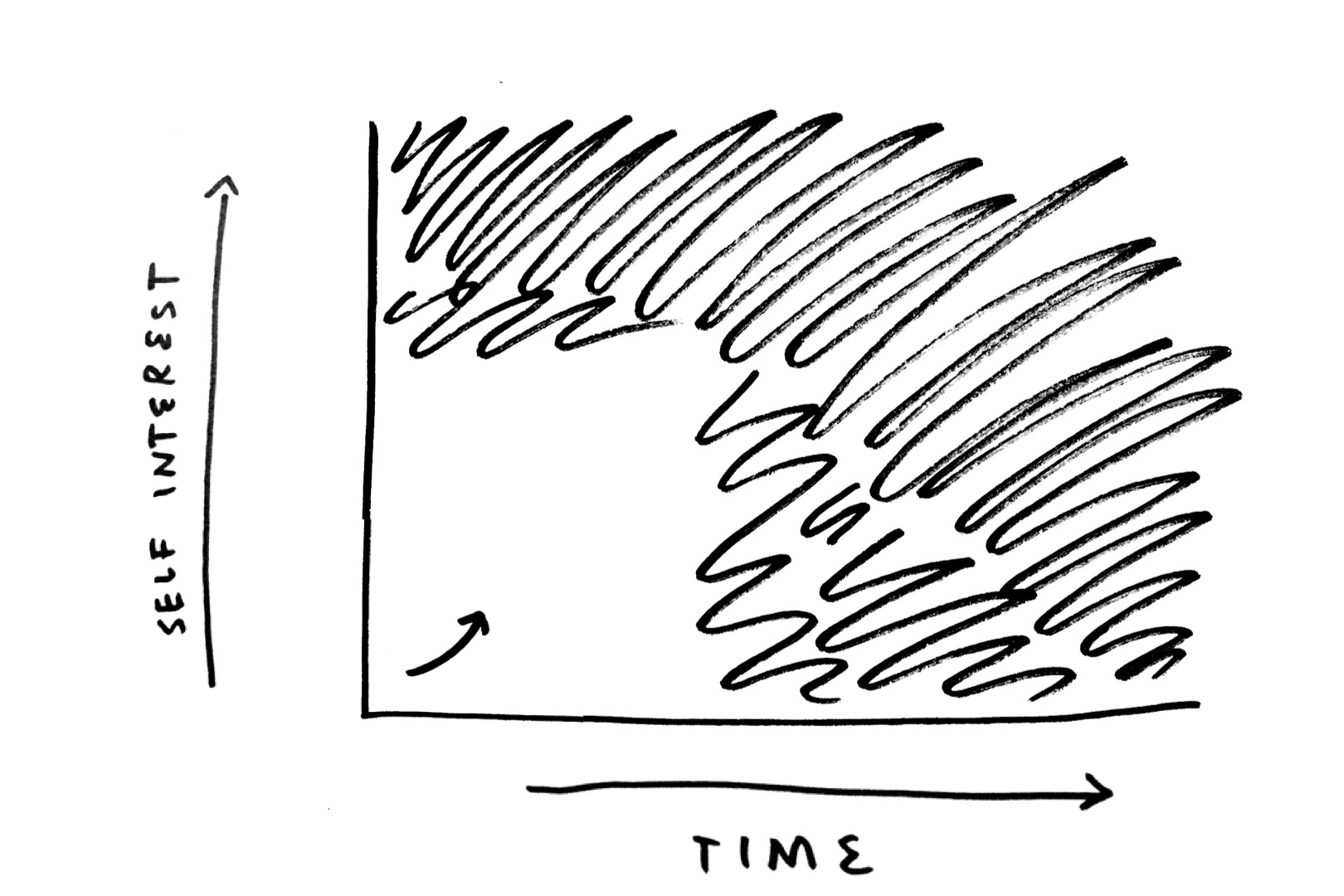

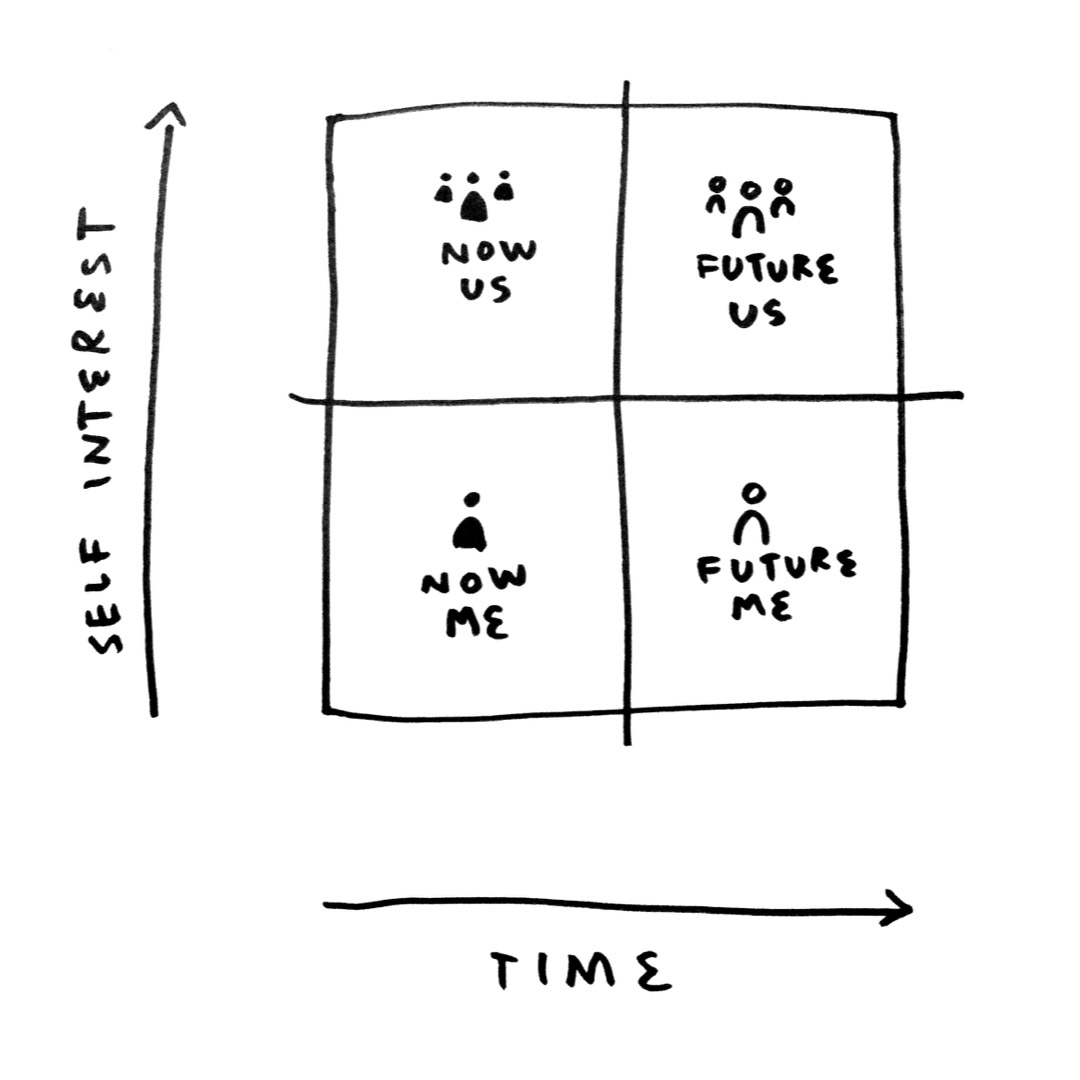

Our self-interest doesn’t stop with us right now. It keeps going — on both axes. The Time axis extends from now all the way into the future. And the Self-interest axis extends from you (“Me”) to your family, friends, and communities (“Us”). As our self-interest grows, so does its impact.

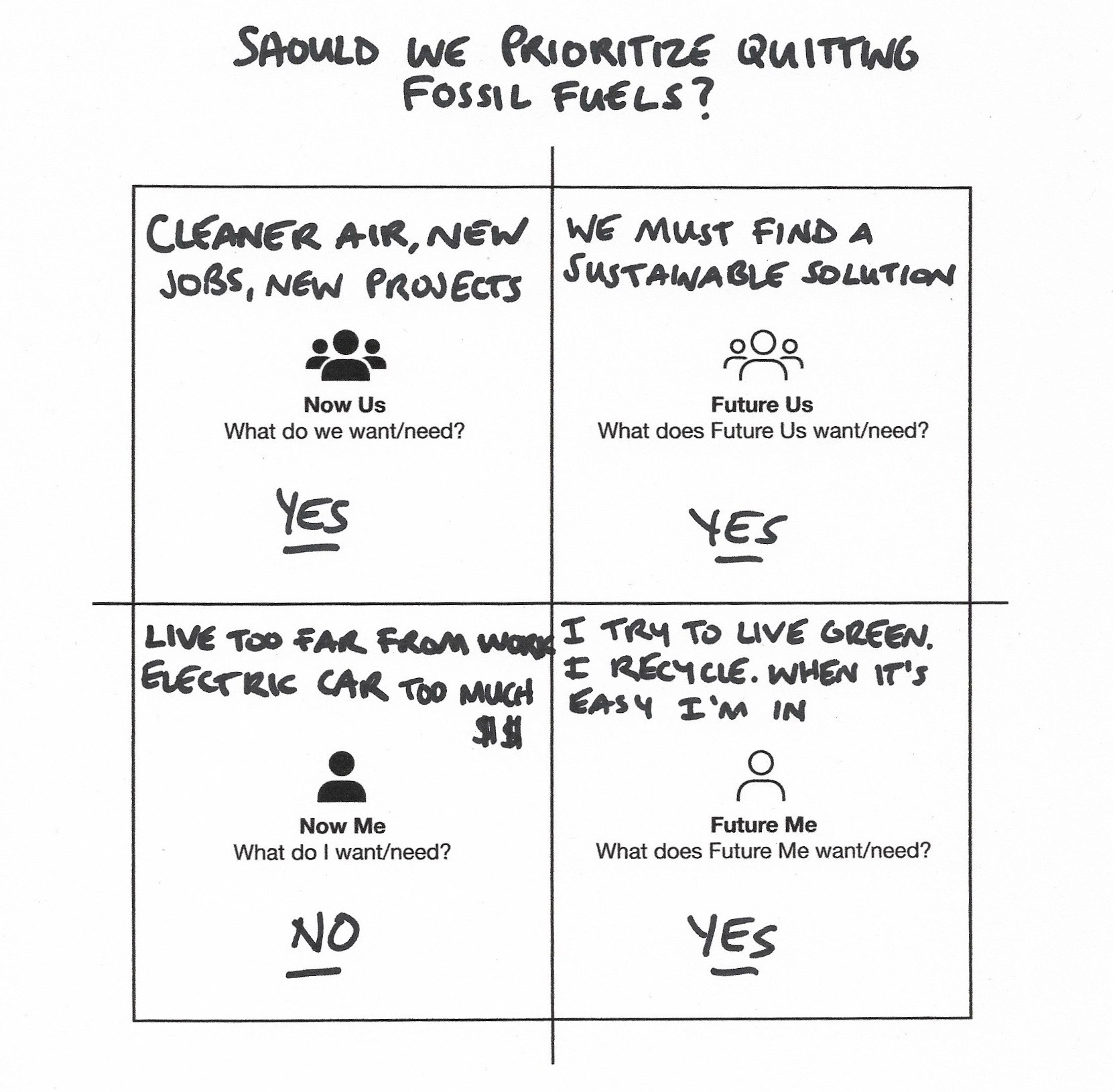

In this expanded view of self-interest, what we want right now is there (Now Me). But so are other rational perspectives. The people we care about and are responsible for (Now Us). Our future self who wants us to live up to our values and ideals (Future Me). How our decisions affect our children’s future and everybody else’s future, too (Future Us). Each of these spaces impacts us and is impacted by us. They are all in our rational self-interest.

The mistake we make today is believing that Now Me is all there is. We’re pointing a flashlight into the darkness believing we’re seeing the whole universe. We’re not. Our self-interest is bigger than we think.

This is a “Bentoist” way of seeing the world. Just as a bento box provides convenient balance, a Bentoist perspective does the same for our self-interest.

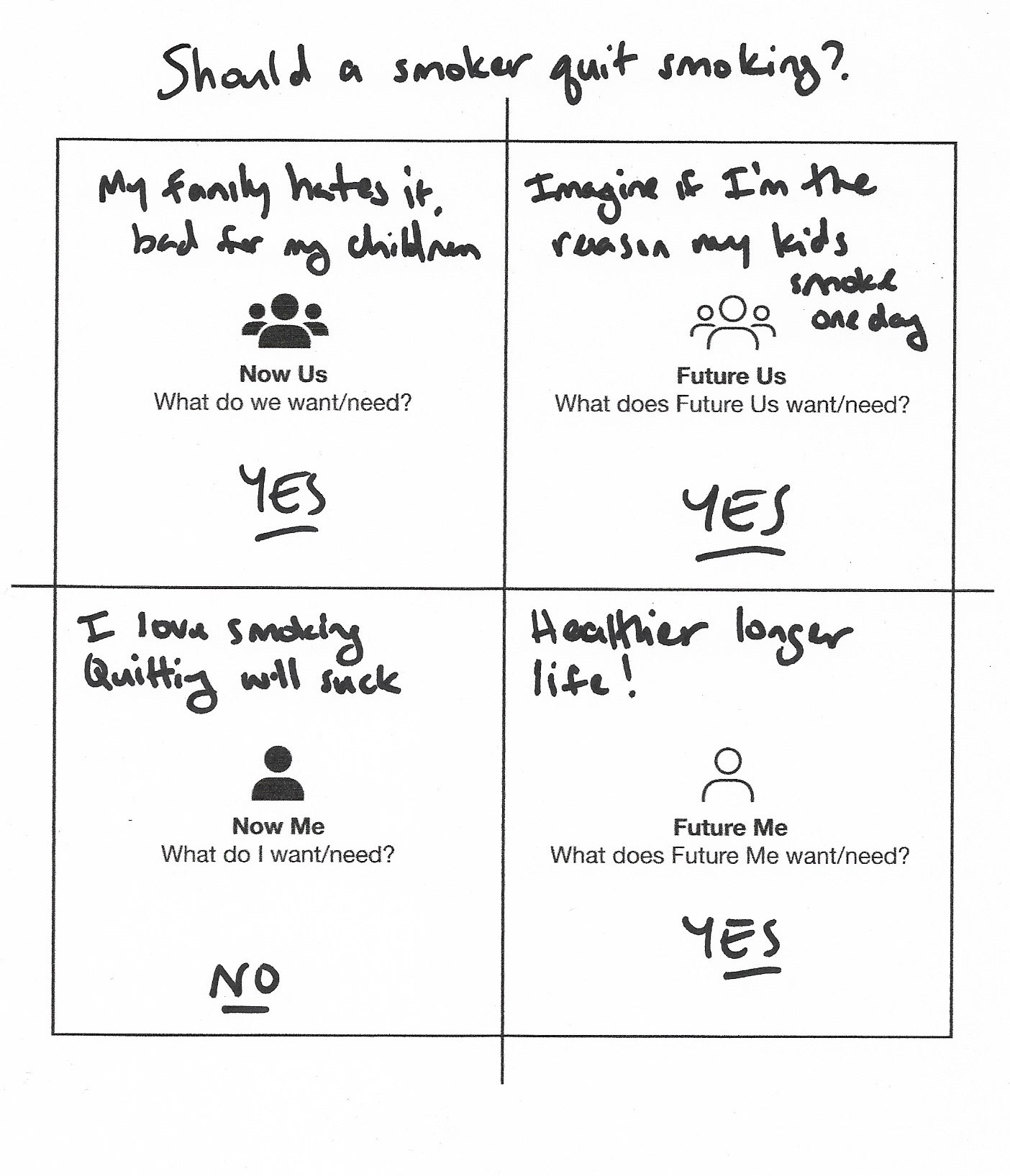

We don’t have a singular notion of self-interest. We’re often balancing different, equally rational, and sometimes competing points of view. Take quitting smoking. If a smoker asked each box whether they should quit, they’d get a variety of responses.

The smoker’s Now Us voice would say to quit. Their family hates it. So would their Future Us. What if their kid starts to smoke because of them? Future Me would definitely say to quit because it wants there to be a Future Me. But the smoker’s Now Me? It says to keep smoking.

Now Me isn’t irrational. It’s addicted to nicotine. It loves smoking. The pain of quitting is hell. Who in their right mind would choose such a thing? Now Me has a valid point based on its limited—but rational—perspective. This is where many smokers (like me, once upon a time) get stuck.

The climate crisis is similar. Should we do everything we can to keep global temperatures within 1.5 degrees of warming, like quit fossil fuels?

Now Us, Future Us, and Future Me say yes. For future human existence to resemble anything like ours today, our energy sources must change. But Now Me says no. Changing is inconvenient. Expensive. We’d rather borrow from tomorrow to pay for today.

In cases like quitting smoking or carbon emissions we are most likely to change our behavior when our Now Me forces us to. We quit smoking after a lingering cough or a scary doctor’s visit. We start believing in climate change after the rising waters destroy our property or rip a loved one away. By then it can be too late.

Far better is to become aware of our true self-interest before that happens. That’s what warning labels on cigarettes are meant to help us do, and what Extinction Rebellion, Greta Thunberg, and others are doing with the climate crisis. By exposing us to the truth, they invite us to act in our true self-interest.

The original bento box honors a Japanese eating philosophy called hara hachi bu, which says the goal of a meal is to be 80% full. That way you’re still hungry for tomorrow. By design, the bento ensures a balanced meal and balanced life.

We’ve been eating like there’s no tomorrow, and now tomorrow’s very existence is in doubt. We’re trapped by a limited understanding of our self-interest. We can escape once we start seeing the whole picture.

From THIS COULD BE OUR FUTURE by Yancey Strickler, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Yancey Strickler.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com