2017 ended as a banner year for my family, but things didn’t look great at the start. A death sentence met us in a boxing ring, and we had to school ourselves on fighting to live. I never thought much about the 37 million American adults who suffer from kidney disease until my husband Neil became one of them.

Celebrating our first year of marriage in 2001, we learned by accident through an unrelated medical exam that my husband has polycystic kidney disease, an illness which causes the kidneys to fill with cysts over time, rendering the organs unable to function properly. There is no cure. There was nothing to do but wait for my husband’s kidney function to decline below 20%, the point at which either dialysis or a transplant would be considered to prolong life.

It would be 16 more years before Neil would enter end-stage renal failure, the final, permanent phase of chronic kidney disease where the organs no longer function, and in early 2017, he joined the waitlist for a transplant, alongside some 100,000 others in the U.S. Those on the waitlist face a three-to-10 year wait for a deceased donor kidney, and the statistics are grim. Kidney disease is the ninth most common cause of death in the U.S., and while Medicare covers the cost of dialysis for kidney failure, it is an exhausting treatment process with low survival rates. America’s kidney shortage kills 43,000 people per year, as those on the waitlist sit hoping for “the call” that an organ has become available.

Much hope was given to kidney disease patients in July when the federal government announced an executive order aimed at overhauling the care of kidney disease. The move aims to reduce the number of kidney failures by early monitoring and preventative care, and to make more kidneys available for transplant by examining the rate of discarded kidneys from deceased donors. The administration also plans to address disincentives to living donation such as financial hardship during time off work.

While this call to action is long overdue, continued education is needed to empower patients to navigate the transplant process. We were bombarded with a plethora of medical information during my husband’s extensive transplant evaluation, but we received no guidance about his best shot at a long and healthy life: a kidney from a living donor. Determined not to watch my husband deteriorate on the deceased donor waitlist, I went to work finding a living kidney donor, a challenging job that typically falls on the patient or family members. I quickly learned that having a willing donor is a far cry from having an approved donor.

Living-donor criteria are very stringent in order to protect the donor’s long-term health. While each transplant center has its own specific criteria, being overweight, having uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, cancer, or a serious mental health condition can all rule a person out from donating a kidney. During my medical evaluation, I was diagnosed with fibromuscular dysplasia, a progressive twisting and beading of the renal arteries. All the other willing potential donors in our family were also deemed medically ineligible. With this devastating news, we went public with our search for a donor. I spoke about my husband’s plight at local community groups, we printed signs and cards to post in local businesses, and campaigned on social media. Eventually, a number of people came forward to donate and in the end, two teachers at our daughter’s school were approved.

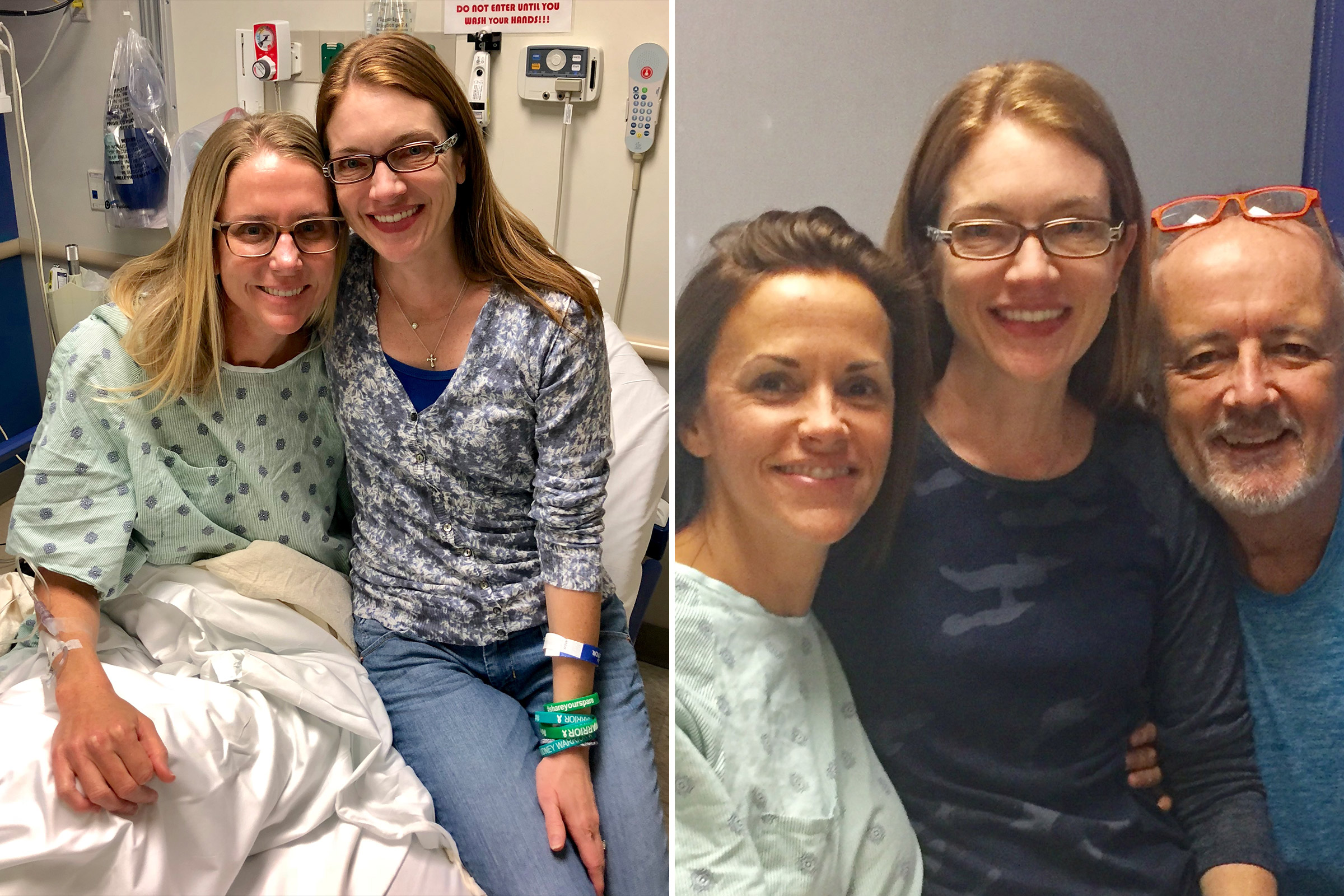

Just prior to my outreach campaign, I had confided in the two teachers, Allison Malouf and Britani Atkinson. Malouf knew the process well as her husband had donated in 2010, and she expressed immediate interest in being tested as a donor. Atkinson, like many others, offered support by listening to the anguished desperation in my voice, unloading my dishwasher, sharing our posts on social media, and folding laundry I had ignored or no longer had the mental stamina to face. While Malouf kept me informed of every step of her months-long evaluation process, Atkinson was also hard at work being secretly evaluated by the same medical team. She’d chosen to do all the medical testing behind our back, so to speak, so as not to dishearten us if she were also denied as a donor. Persistence paid off, and Atkinson was the first approved donor for Neil, followed by Malouf a few weeks later.

Neither Atkinson nor Malouf was a good biological match for Neil. But these days, it’s a myth that you have to be a “match” to save your intended recipient. The National Kidney Registry’s kidney swap program has developed a large pool of mismatched donor/recipient pairs scattered across the country. Its algorithms find blood-and-tissue-compatible pairs, and it sets up a “kidney chain” in which kidneys are flown across the country and evenly exchanged. It is very unusual for a recipient to have more than one approved donor, but both Atkinson and Malouf were determined to help. They enrolled to donate a kidney for Neil through the National Kidney Registry’s paired exchange program at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

With my husband’s kidney function dwindling to 11%, a lifesaving chain was assembled just in time for him to avoid dialysis in the summer of 2017. Although Atkinson is a universal donor with her O negative blood type, her kidney was deemed too small for Neil, and she matched another recipient in the pool fairly quickly. In September of that year, Neil’s donor’s kidney, from a stranger in Los Angeles, arrived at Johns Hopkins Hospital on a redeye flight, while Atkinson’s kidney took an outbound flight to a stranger in Boston. Once Neil was successfully transplanted, Malouf felt compelled to save the life of a child by giving a young boy on dialysis what’s called a “kidney voucher” via a kidney donation to a stranger in San Diego. This unique, non-transferable voucher entitles the designated recipient to a living donor kidney once a match is found within the National Kidney Registry’s donor pool. The two teachers’ kidney donations kicked off separate donation chains which ultimately saved eight lives across the U.S.

“It illustrates the power of living donation and paired exchange,” says Dr. Niraj Desai, Neil’s surgeon. “Two generous living donors were willing to step up and be tested, which led to transplants for multiple recipients.” While those not familiar with the living donation process may have hesitations, Desai notes that “people don’t realize that living kidney donation is an extremely safe procedure. There’s a low risk to donors or we wouldn’t do it.”

While kidney swaps can be performed at most transplant centers across the U.S., the majority are facilitated by the National Kidney Registry. Other swaps are organized by the United Network for Organ Sharing, the Alliance for Paired Kidney Donation, or arranged in-house at the transplant center itself with incompatible patient pairs.

With its unique Donor Shield program, the National Kidney Registry offers unparalleled protection to living donors, including lost wages and travel-expense reimbursement, coverage for complications not covered by Medicare or the recipient’s health insurance, and life insurance. While kidney donors in all centers are prioritized to receive a deceased donor kidney in the unlikely event that the donor’s remaining kidney ever fails, the National Kidney Registry adds invaluable peace of mind to its donors with the guarantee that a donor will be prioritized in its program to receive a living donor kidney. The Registry also has access to the largest kidney pool in the U.S., including some 90 transplant centers across the country.

The National Kidney Registry also offers innovative options to accommodate the donor’s schedule, like voucher programs and advanced donation. While some donor/recipient pairs are blood-type incompatible, there are some who may be chronologically incompatible. For example, a schoolteacher may want to donate during the summer months, but that may not work for the intended recipient. In this case, donors can donate in advance at a time convenient for them and give a kidney voucher to an intended recipient. The recipient in need then gets a voucher, which guarantees a living donor kidney once a match is found in the system. This scenario is, fundamentally, a paired exchange separated in time.

The National Kidney Registry has also gone one step further to remove a major barrier to living donation. One of the biggest reasons people don’t want to part with an organ is the lingering thought, “But what if someone in my family ever needs a kidney?” With the introduction of the family voucher program, non-directed donors, also known as good Samaritan donors, can name up to five family members who will receive a kidney voucher. “Not only does this remove an important disincentive to living kidney donation, but it is the right thing to do for the generous people who are donating a kidney to a stranger. Donors can now donate a kidney and still provide security for their loved ones should they need a kidney transplant in the future,” says Dr. Jeff Veale, director of the Paired Exchange Program at the University of California, Los Angeles and the surgeon who pioneered the first voucher case in 2014.

In a world where hurt and suffering often make the evening news, living donors freely give away a part of themselves to make another whole. Ironically, they often see themselves as the ones receiving a gift. While their cost is short-term discomfort following major surgery, they give an entire lifetime of future memories to another family.

The best gift I’ve never laid eyes on keeps my husband alive, and it has infused our family with invigorating vitality and renewed appreciation. Even so, going public with our story was one of the biggest hurdles we faced. Like my husband, many patients in need feel they are burdening others by the mere thought of asking for a kidney, let alone accepting one. Conversely, living a life tethered to a machine is not only detrimental to the physical and mental well-being of the patient, but family members suffer tremendously by watching their loved one weaken over time. Pride or shame should never be listed as a cause of death, yet some patients describe the odyssey of finding a living donor and accepting the gift as more daunting than the transplant itself. Just as kidneys are rare commodities, the courage to be vulnerable is hard to come by. Our journey demonstrates the higher the risk, the greater the reward. We rolled the dice and gambled on the magnificence of mankind. We won, and others can too.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com