Javius Lamar Mitchell was a typical 11-year-old kid: he loved watching the Walking Dead on Netflix, playing Madden NFL 2019 on his PlayStation 4, and going to after-school football practice in his small, rural town of Hughes Springs, Texas. But there was one key difference between Mitchell and his tween compatriots in cities and suburban areas around the country: how far he lived from a hospital.

While the average distance to an emergency room is 5.6 miles in suburban areas, and 4.4 miles in urban ones, according to a 2018 report by Pew Research Center, the closest hospital to Mitchell’s house was 24 miles away. That difference may have been fatal.

On Aug. 9, when Mitchell suffered a severe asthma attack, it took emergency services 45 minutes to get him to a hospital. Despite paramedics’ best efforts, his asthma attack narrowed his airway so much that the supplemental oxygen they provided him couldn’t get to his brain. A week later, his mother NaTasha Holloman had to make the devastating decision to withdraw life-sustaining care from her son, whom she described to TIME as “sweet, smart and understanding.”

“The town let us down. The town let him down,” said Barbara Brown, Mitchell’s aunt who has been lobbying local leaders to open a community clinic in the days since her nephew’s death.

The circumstances that likely contributed to Mitchell’s death are becoming more common. As hospitals consolidate and close and medical specialists move to more densely populated areas, the people who live in rural towns like Hughes Springs are increasingly at risk. And it’s becoming a political flashpoint. With the closest hospital in rural areas now an average of more than 10 miles away — and Democrats presidential hopefuls increasingly in need of rural votes — candidates are beginning to unveil plans designed to solve this growing accessibility crisis.

“You have New Hampshire and you have Iowa,” says Lauren Crawford Shaver, a Forbes Tate public affairs partner and an alum of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign, pointing out the two states with significantly rural populations are first to caucus and vote in the 2020 primary. “And you’ve got to have plans to make sure that all of those states and all the communities in those states are accounted for.” Though rural areas have long backed Republican candidates, the GOP’s stronghold on America’s heartland has only gotten stronger in recent years: fully 62% of voters backed Trump in 2016, versus 59% support for the Republican candidate in 2012, and 53% in 2008, according to exit polls.

“You cannot, certainly, win the Senate back, but probably not even win the presidency, without increasing the margin of Democratic votes in rural America,” former Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, a North Dakota Democrat who now serves on the board of the rural revitalization One Country project, told TIME.

The root causes of this crisis of rural medical accessibility are complicated. One major factor is a nationwide shortage of physicians, especially primary care doctors, willing to take on large medical school debt to work in rural areas where they can expect relatively modest salaries compared to their peers working in urban areas. Rural areas have a higher population of patients on Medicare and Medicaid, which means that doctors, medical specialists and hospitals receive lower reimbursements from them. Rural patients are also on average older and sicker than their suburban and urban counterparts, which means it costs more to treat them. Put simply, treating rural populations doesn’t make sense from a business perspective, and it’s becoming harder to find doctors willing to do that work.

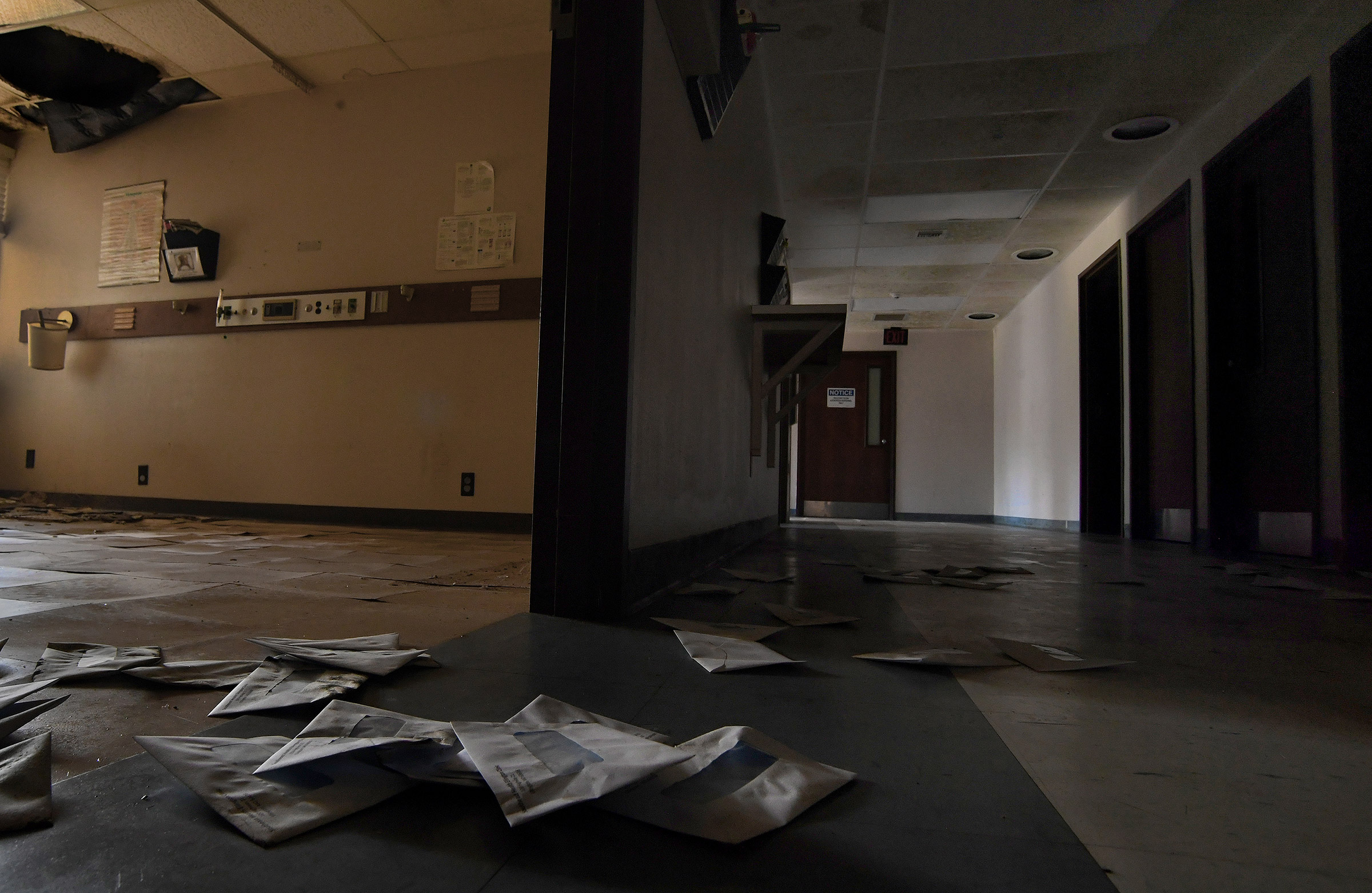

The result has been rural flight: Some 160 rural hospitals have closed since 2005, with 69% of those having shuttered since 2012. And while there are 263 medical specialists per 100,000 people in urban areas, rural areas now average only 30, according to the National Rural Health Association. The decline in accessible rural medical care is coming just as people in rural areas need it more than ever: Rural populations, on average, face higher rates of diabetes, coronary heart disease and fatal cancer.

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren has one of the most comprehensive plans to address this problem. In addition to supporting Medicare-for-all, which would replace private health insurance plans with a single-payer government-run system, the Massachusetts progressive would also offset the physician and specialist shortages by targeting half of new residency placements in medically-underserved areas, and by expanding student loan forgiveness funding for doctors who work in underserved areas. She has also proposed reimbursing rural hospitals at a higher rate than urban ones, increasing funding for community health centers by 15% per year over the next five years, and establishing a $25 billion capital fund to support measures like constructing new birthing centers, which are especially scarce in rural towns.

Despite 20% of Americans living in rural areas, only 6% of the nation’s OBGYNs serve them, according to the latest survey numbers from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Less than half of rural women live within a half-hour of a hospital that offers perinatal services, the group says.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, who rose to national prominence before the 2016 election for backing universal health care (“I wrote the damn [Medicare-for-all] bill,” he says), has offered a plan of his own. His would expand funding for rural health centers, as well as for the National Health Service Corps, which places health care providers in underserved areas. “Health care is a major concern for rural voters, and Democratic primary voters trust Bernie above all others on health care issues,” one of his spokespeople told TIME.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, meanwhile, has focused his attention on community health centers and educating new doctors. His plan would double federal funding for community health centers, and develop partnerships between high schools, community colleges and health centers in hopes of inspiring students to pursue health-related careers in rural areas. Along with corporate lawyer turned entrepreneur turned Democratic contender Andrew Yang, Biden also proposes deploying cost-efficient videoconferencing and other telehealth services to areas where specialists are lacking.

Rural health advocates, while open to telehealth services, point out that they are limited in emergencies. To be sure, a doctor-to-patient video chat likely wouldn’t have saved Mitchell’s life. It also wouldn’t have helped Kati Stieler, a part-time teacher whose rapid labor almost resulted in her second child being born on the side of a two-lane highway.

In Stieler’s case, the closest hospital with a labor and delivery department was more than 100 miles—a two hour drive—from her home in Grand Marais, Minnesota. When she went into labor in August, it was 2 a.m. and pouring rain. “I therefore spent the drive tensing my whole body trying to keep my baby in and slow down labor, all while shouting, ‘This is HORRIBLE! THIS is HORRIBLE!’” Stieler told TIME in an email. As Stieler’s contractions intensified, her OBGYN told her and her husband to turn around and head to the nearest emergency room, where she delivered 12 minutes after they arrived. Both she and her baby boy were healthy, but it was hardly an ideal experience. Much of her stress would have been relieved, she says, had a birthing center been closer to home, preventing the anxiety that her child would be born on the side of the road. “My first words when we got out of the car were, ‘I don’t want to be here!’ with tears running down my cheeks,” Stieler said. “Everything I had been told was that we were not supposed to go to our local hospital and our babies were supposed to be born in Duluth.” The doctor who delivered her baby was not an obstetrician and had anything gone wrong, the hospital would not have been equipped to provide neonatal intensive care.

“There is something broken in our system, and it needs to change,” said Stieler. It’s a sentiment that many rural people would agree with—and may very well vote on next year.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abby Vesoulis at abby.vesoulis@time.com