The death of Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi may not change the world. Nevertheless, how it came about says a fair amount about the world he has departed.

In the chain of events that led to the Oct. 26 demise of the ISIS leader, every link tells a story. But even as it crystallizes what the war on terrorism looks like 18 years after 9/11, al-Baghdadi’s death may mark the beginning of an uncertain new chapter.

The first link begins with the government of Iraq, which in September arrested one of al-Baghdadi’s wives and a courier. Intelligence pointed to Syria, where the CIA was already working with the Kurdish militia. Both Iraq and the Kurds are committed enemies of ISIS. Iraqis suffered tens of thousands of casualties pushing ISIS out of their country from 2014 to 2017, and Kurdish militias lost some 11,000 fighters finishing the job in Syria, where the group’s claim of a caliphate was erased.

Their involvement underscores that this is a global fight: the U.S. is not going it alone. The people actually prosecuting the war on terror are overwhelmingly local and Muslim–in Iraq and Syria, but also in Libya, Niger, Chad, Mali, Somalia, southern Yemen and much of Afghanistan, where more than 58,000 Afghan national military and police forces lost their lives through 2018. Typically the U.S. military role in these missions is restricted to half a dozen or more special-operations commandos working with local forces by providing intelligence, training and air cover. The local forces are mostly Muslim.

Kurdish fighters in Iraq and Syria continued to battle ISIS and hunted al-Baghdadi even after American forces retreated from those countries. On Oct. 6, Trump ordered U.S. troops to pull back from territory held by the Kurds, who were left alone to face an attack by Turkey. “I don’t think we could have done this without the help we got from the Syrian and Iraqi Kurds,” a U.S. official told TIME, speaking of the operation against the ISIS leader. The official quickly added that Iraq military and intelligence officers “kicked the whole thing off.”

Al-Baghdadi’s trail led east. He appeared to have gone to ground not near the lush Euphrates valley where ISIS fighters made their last stand in Syria–and where his fighters still mount ambushes and suicide attacks–but in Idlib province, the last large section of Syria still controlled by rebel militias, which in turn are dominated by an affiliate of al-Qaeda. That’s the next link in the war on terrorism: it’s far from over. Militant Islam may hold scant appeal to the overwhelming majority of the world’s 1.8 billion Muslims (a 2015 Pew Center survey found almost no more support for ISIS in Lebanon than in Israel), but a terrorist attack does not require great numbers, and chaos gives extremism both oxygen and maneuvering room. Not by chance are ISIS, al-Qaeda and their offshoots found in the globe’s least-governed locations.

Like Syria. During its eight-year civil war, the country was a proving ground for jihadists, many drawn by the sectarian nature the conflict quickly assumed. The Damascus government of Bashar Assad is dominated by Alawites, a heterodox religious minority. Assad’s brutal answer to peaceful Arab Spring protests by Syria’s Sunni Muslim majority was answered by a range of armed groups, including extremists who dominated the rebel battlefield. ISIS was a latecomer, having begun across the desert border as al-Qaeda in Iraq. There ISIS fought the U.S. occupation while slaughtering Shi’ite Muslims and religious minorities.

Al-Baghdadi, born Ibrahim Awad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri 48 years ago in a village in central Iraq, took his nom de guerre from the capital city, where he got a Ph.D. in Quranic studies. He was swept up in arrests by U.S. forces in 2004 and, during almost a year in custody, turned his prison tent into an incubator of extremism. After release he joined the armed group he would in 2010 come to lead. All three of the leaders who preceded him, including the notorious Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, were killed by U.S. forces in tandem with the Iraqi government.

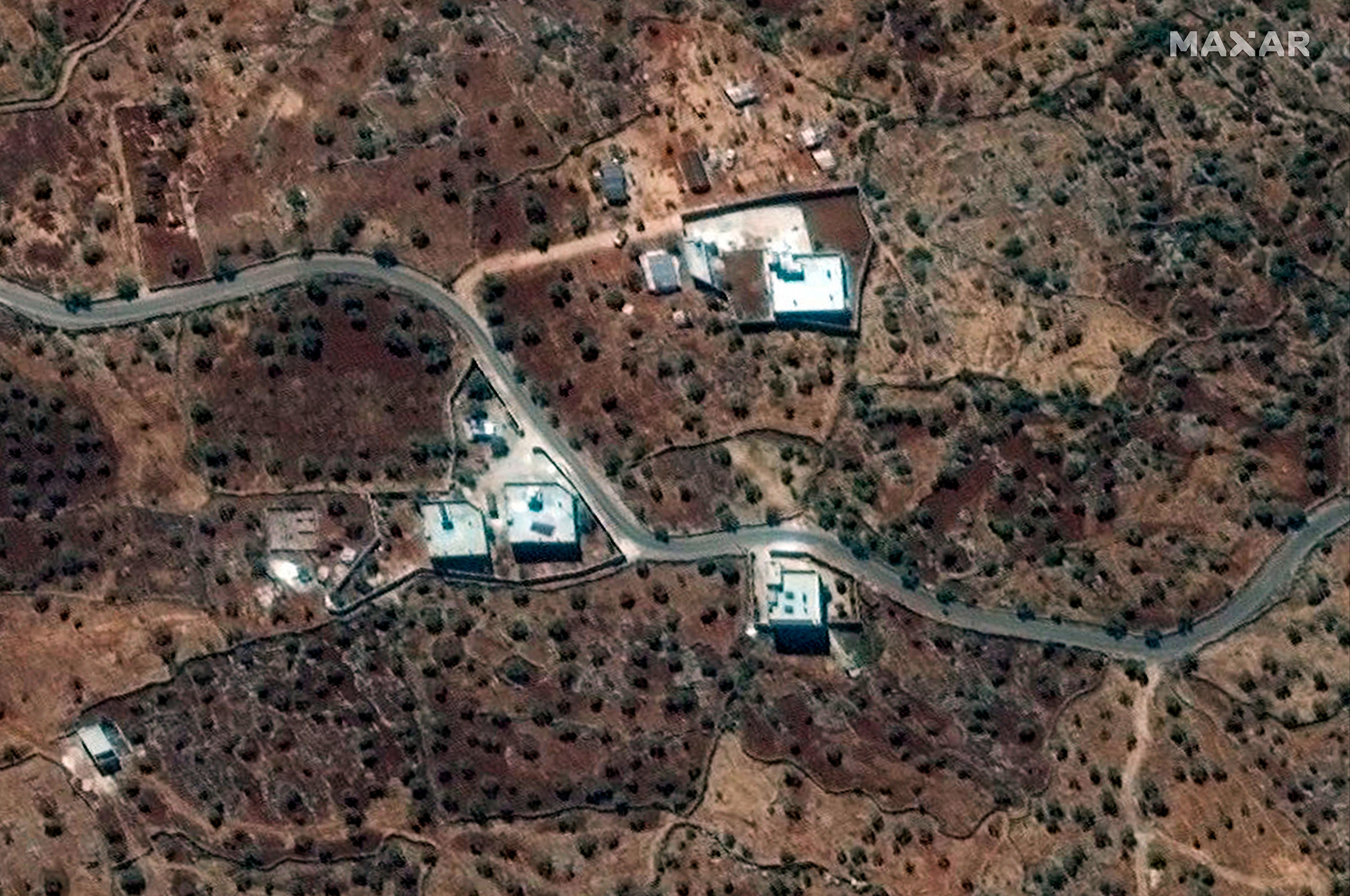

That collaboration formed the next link in the chain that led to al-Baghdadi’s death. This story is one of professional cooperation, shared goals and keeping everyone on the same page. By doctrine and training, U.S. special-operations forces work jointly with others, from the CIA to the Iraqi military and intelligence and the Syrian Kurds who dispatched agents along the routes al-Baghdadi was thought to use, tracing him to a compound near the Turkish border.

The Kurds had a man on the inside, their general Mazloum Abdi told reporters afterward. Abdi said a member of al-Baghdadi’s security detail smuggled out soiled underwear, and even a blood sample, for DNA testing that confirmed the ISIS leader’s presence. The agent also described the layout of the compound in detail, including a tunnel. (The reward for information leading the U.S. to al-Baghdadi was $25 million.) Planning began for a capture-or-kill operation carried out by the Army’s elite Delta Force and Ranger Regiment troops. The mission was named in part for Kayla Mueller, the U.S. aid worker kidnapped by ISIS in 2013 and raped by al-Baghdadi.

On Oct. 26, the operation went off without incident, commandos flying from Iraq in eight CH-47 Chinooks and other helicopters, breaching a high wall surrounding the compound and pursuing al-Baghdadi into the tunnel, a dead end where he detonated a suicide vest, killing the two children he’d taken with him. President Donald Trump watched the video feeds in the White House Situation Room “like a movie,” he said in an announcement the next morning.

But Trump himself had disrupted planning. His abrupt announcement that the U.S. was leaving Kurdish territory in Syria infuriated the U.S. partners in the operation. As the U.S. retreated, and the Kurds scrambled for their lives while under attack by Turkey, raid planners scrambled to coordinate logistics, air power and other military assets required for the operation against al-Baghdadi.

And so the impact of al-Baghdadi’s elimination (and the data recovered from his compound) is not the only question left looming in the aftermath of the raid.

ISIS has operated as an insurgency, a militia, a government and, perhaps most dangerously, as a movement, inspiring followers despite its astonishing brutality. “Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s death–welcome and important though it may be–is not a catastrophic blow to the quality of leadership in ISIS,” says Michael Nagata, who retired in August as Army lieutenant general and strategy director from the National Counterterrorism Center. Nagata, who served in the Middle East as a special-operations commander in 2014 when the counter-ISIS campaign began, says ISIS now has a cadre of young, battle-hardened leaders who are climbing its echelons and in the terrorist group’s global network. “ISIS isn’t a crippled organization because Baghdadi’s gone,” he says. “The depth and breadth of ISIS leadership, in my judgment, is unprecedented for this type of terrorist group.”

Nor does killing al-Baghdadi reverse Trump’s betrayal of the Kurds. The decision has raised doubts even in Iraq, where the U.S. lost thousands of troops and spent $1 trillion. “The staying power of the United States is being questioned in a very, very serious way,” the President of Iraq, Barham Salih, told Axios in an interview. “And allies of the United States are worried about the dependability of the United States.”

Iraq declared that troops Trump ordered out of Syria can’t stay there, opening the question of how the U.S. will suppress an ISIS that “is stronger today than its predecessor al-Qaeda in Iraq was in 2011, when the U.S. withdrew from Iraq,” as the Institute for the Study of War wrote in a June report. “ISIS’s insurgency will grow because areas it has lost in Iraq and Syria are still neither stable nor secure.”

After Russian and Turkish forces took over territory once held by the Kurds and Americans, Trump ordered a rump U.S. force to protect nearby oil fields. The move underscored the betrayal of the Kurds and reinforced perceptions that the West cares most about resources–never a good outcome in a contest for hearts and minds. After al-Baghdadi, there can be no question such a contest matters.

“It’s good to take out the leader, but it’s not just a terrorist group–it’s an ideology as well,” says Aki Peritz, a former CIA counterterrorism analyst. “Stamping out the idea of the Islamic State will prove to be much more difficult than one successful military-intelligence operation.”

–With reporting by JOHN WALCOTT/WASHINGTON

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to W.J. Hennigan at william.hennigan@time.com