Artificial intelligence has the potential to radically change health care. Imagine a not too distant future when the focus shifts away from disease to how we stay healthy.

At birth, everyone would get a thorough, multifaceted baseline profile, including screening for genetic and rare diseases. Then, over their lifetimes, cost-effective, minimally invasive clinical-grade devices could accurately monitor a range of biometrics such as heart rate, blood pressure, temperature and glucose levels, in addition to environmental factors such as exposure to pathogens and toxins, and behavioral factors like sleep and activity patterns. This biometric, genetic, environmental and behavioral information could be coupled with social data and used to create AI models. These models could predict disease risk, trigger advance notification of life-threatening conditions like stroke and heart attack, and warn of potential adverse drug reactions.

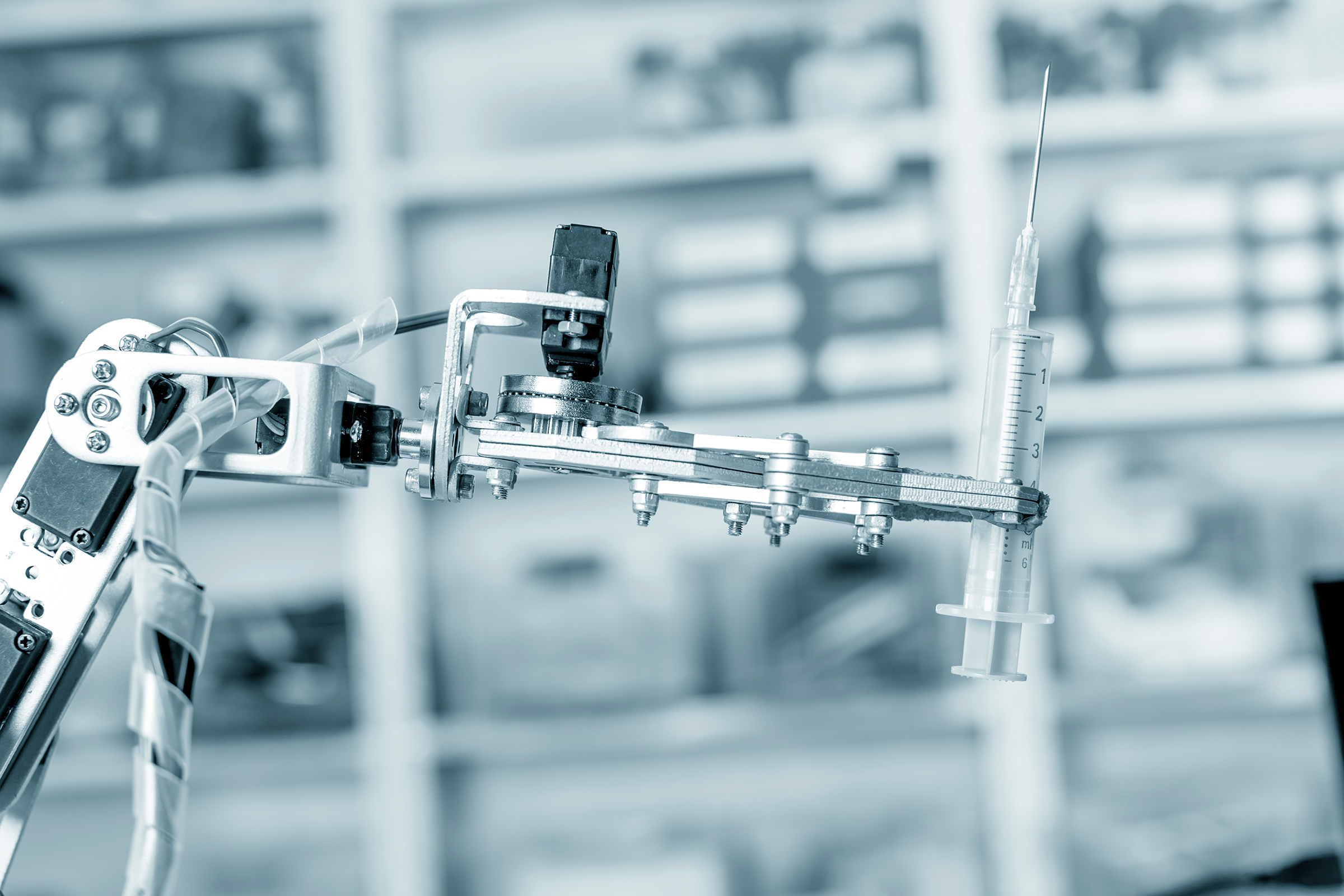

Health care of the future could morph as well. Intelligent bots could be integrated into the home through digital assistants or smartphones in order to triage symptoms, educate and counsel patients, and ensure they’re adhering to medication regimens.

AI could also reduce physician burnout and extend the reach of doctors in underserved areas. For example, AI scribes could assist physicians with clinical note-taking, and bots could help teams of medical experts come together and discuss challenging cases. Computer vision could be used to assist radiologists with tumor detection or help dermatologists identify skin lesions, and be applied to routine screenings like eye exams. All of this is already possible with technology available today or in development.

But AI alone can’t effect these changes. To support the technical transformation, we must have a social transformation including trusted, responsible, and inclusive policy and governance around AI and data; effective collaboration across industries; and comprehensive training for the public, professionals and officials. These concerns are particularly relevant for health care, which is innately complex and where missteps can have ramifications as grave as loss of life. There will also be challenges in balancing the rights of the individual with the health and safety of the population as a whole, and in figuring out how to equitably and efficiently allocate resources across geographical areas.

Data is the starting point for AI. And so we need to invest in the creation and collection of data–while ensuring that the value created through the use of this data accrues to the individuals whose data it is. To protect and preserve the integrity of this data, we need trusted, responsible, inclusive legal and regulatory policies and a framework for governance. GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) is a good example: in the E.U., GDPR went into effect in May 2018, and it is already helping ensure that the health care industry handles individuals’ information responsibly.

Commercial companies cannot solve these problems alone–they need partnerships with government, academia and nonprofit entities. We need to make sure that our computer scientists, data scientists, medical professionals, legal professionals and policymakers have relevant training on the unique capabilities of AI and an understanding of the risks. This kind of education can happen through professional societies like the American Society of Human Genetics and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which have the necessary reach and infrastructure.

Perhaps most important, we need diversity, because AI works only when it is inclusive. To create accurate models, we need diversity in the developers who write the algorithms, diversity in the data scientists who build the models and diversity in the underlying data itself. Which means that to be truly successful with AI, we will need to overlook the things that historically set us apart, like race, gender, age, language, culture, socioeconomic status and domain expertise. Given that history, it won’t be easy. But if we want the full potential of AI to be brought to bear on solving the urgent needs in global health care, we must make it happen.

Miller is a director of artificial intelligence and research at Microsoft, where she focuses on genomics and health care

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com