It’s standing room only in Eddy’s kitchen, a tiny deli with mismatched floor tiles and laminated menus in North Plainfield, N.J., when Democratic Congressman Tom Malinowski begins explaining why he supports the impeachment inquiry into President Donald Trump. “What is the difference between the United States of America and Russia? What is the difference between the United States of America and Venezuela?” he asks. American politicians, he says, “put their duty to their country, to their people first–ahead of their duty to themselves.” Trump, Malinowski charges, broke that pact when he asked the Ukrainian President in a July 25 phone call to do him a “favor” by investigating one of his political rivals: “Not ‘us, America’ a favor,” he says, “but ‘me’ a political favor.”

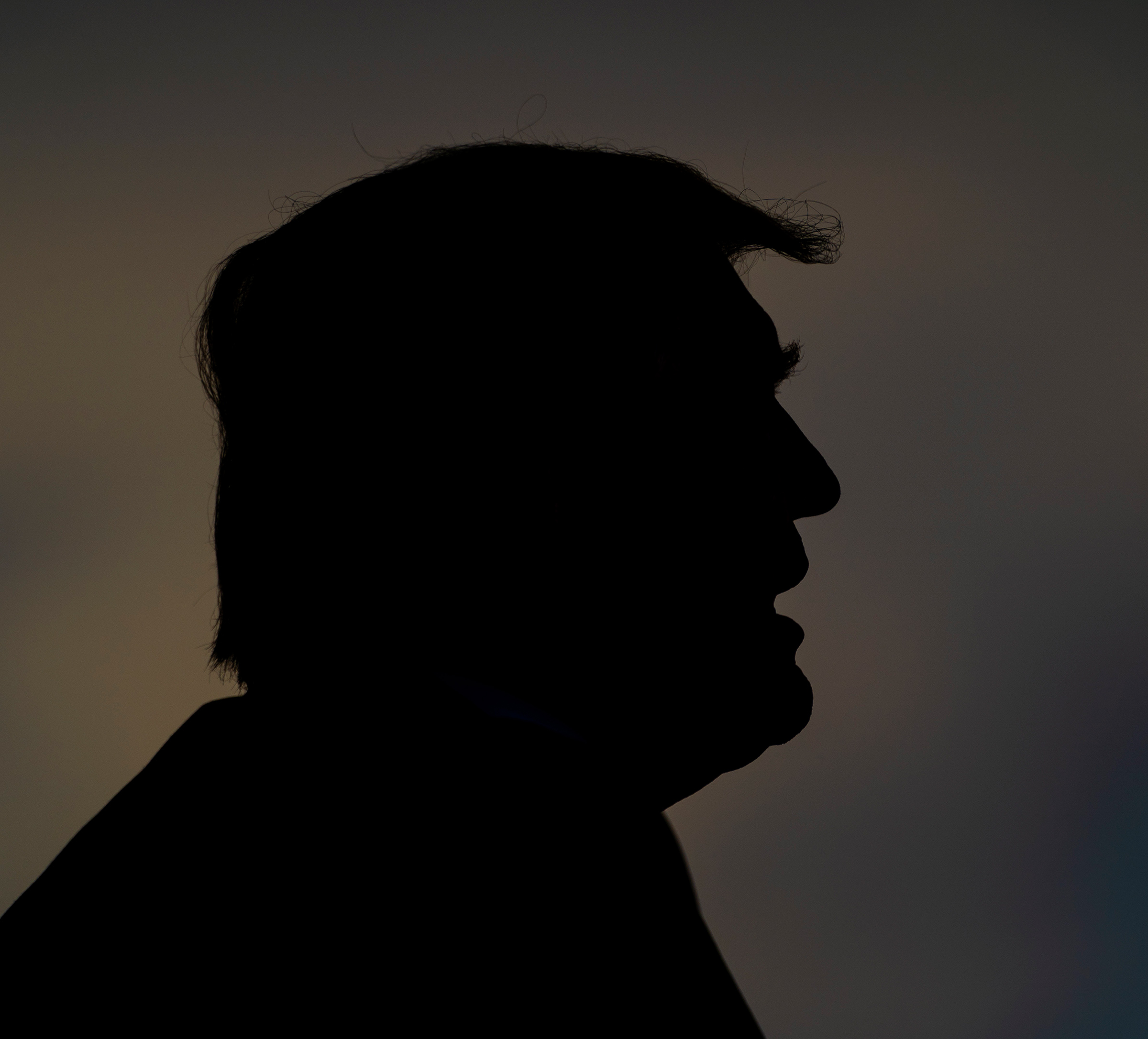

As Washington gears up to judge whether Trump abused the power of the presidency, Congress and the White House are preparing for months of procedural and legal battles over subpoenas, testimony and the balance of power between the coequal branches of government. But in Malinowski’s district and across the country, the impact is more immediate. Control of the House, the Senate and the presidency may hinge on how voters in a handful of state and local races react to the constitutional crisis unfolding in Washington when they go to the polls in November 2020. For Democrats and Republicans, the fight to win the politics of impeachment has already begun.

In Malinowski’s narrowly Republican district, for example, three GOP challengers have already announced a run for his seat. Elsewhere, Democrats are particularly vulnerable in the 31 districts where voters went for Trump in 2016 but elected Democratic House members in 2018. Democrats can afford to lose just 17 of those races next year and retain a majority in the House. Political operatives in both parties are doing similar math to identify the handful of Senate races most at play in the impeachment battle. The Democratic presidential candidates, and the Trump campaign itself, are already adjusting their 2020 strategies to account for the coming impeachment battle. On Oct. 9, Joe Biden became the latest Democratic contender to call for Trump’s impeachment.

So far, Democrats are presenting the issue as a narrow, moral one. Impeachment is not about disliking the President, they say; it’s about preserving the rule of law. Republicans are framing the issue as an unconstitutional attempt to pre-empt the will of the voters and overturn the 2016 election results. Which argument wins may determine the U.S. political map for years to come.

At first blush, the polls look good for Democrats. After the White House released a transcript on Sept. 24 that showed Trump pushing the Ukrainians to investigate Democratic front runner Biden, public opinion swung against the President. Roughly two-thirds of voters found Trump’s request inappropriate, and 61% agreed with the Democrats’ subsequent announcement of an impeachment inquiry, according to an early-October Washington Post survey. Since May, support for impeachment has risen eight points among Republicans and 11 points among independents, according to a CNN survey. Public support for impeachment is now higher than it was when the House launched proceedings against Presidents Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton, and the trend has cheered Democrats. “The movement among independent voters is significant and profound,” says Jesse Ferguson, a 2016 aide to Hillary Clinton.

But national polling tells only part of the story. The Republican National Committee announced it planned to spend $2 million on broadcast ads blasting impeachment, and the President’s re-election campaign has spent nearly $1.2 million on impeachment-themed Facebook ads. The House Republicans’ campaign arm has spent more than $50,000 on Facebook ads targeting Democrats, and its Senate counterpart has spent roughly half that, according to data compiled by Democratic firm Bully Pulpit Interactive. In early October, Vice President Mike Pence visited Iowa and Minnesota to criticize Democrats on the issue.

Democrats’ responses have been less robust. The Democratic National Committee has spent just $12,000–less than 3% of its digital spending–on impeachment-related Facebook ads. For them, the battles are fought locally. Max Rose, whose New York City district went for Trump in 2016, has been careful in his framing of the issue. “We have to make sure the American people understand this is a sad day,” he tells TIME. “But the President brought us to this moment.” In the Senate, the battle is shaping up in Alabama, Arizona, North Carolina, Colorado and Maine–the five races that the Cook Political Report labels as toss-ups or leaning.

For Malinowski, re-election may depend on how much punch he can pack at events like the one at Eddy’s. “I don’t know where this ends,” he tells the crowd, adding, “I want to end up demonstrating that our democracy is still alive. That we still have checks and balances in this country, that we still have the rule of law in the United States of America.”

–With reporting by ABBY VESOULIS/NORTH PLAINFIELD, N.J. and ALANA ABRAMSON/WASHINGTON

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com