Jacques Chirac, who died at 86 on Thursday, towered over French politics for nearly 40 years, first as Mayor of Paris, then as Prime Minister and finally for 12 years as President of France.

The period of his presidency, from 1995 to 2007, marked one of the most profound shifts in Europe, first with the huge expansion of the European Union, and then with the tumultuous aftermath of the Sept.11, 2001 attacks on New York and Washington D.C., where Chirac broke sharply with President George W. Bush on the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

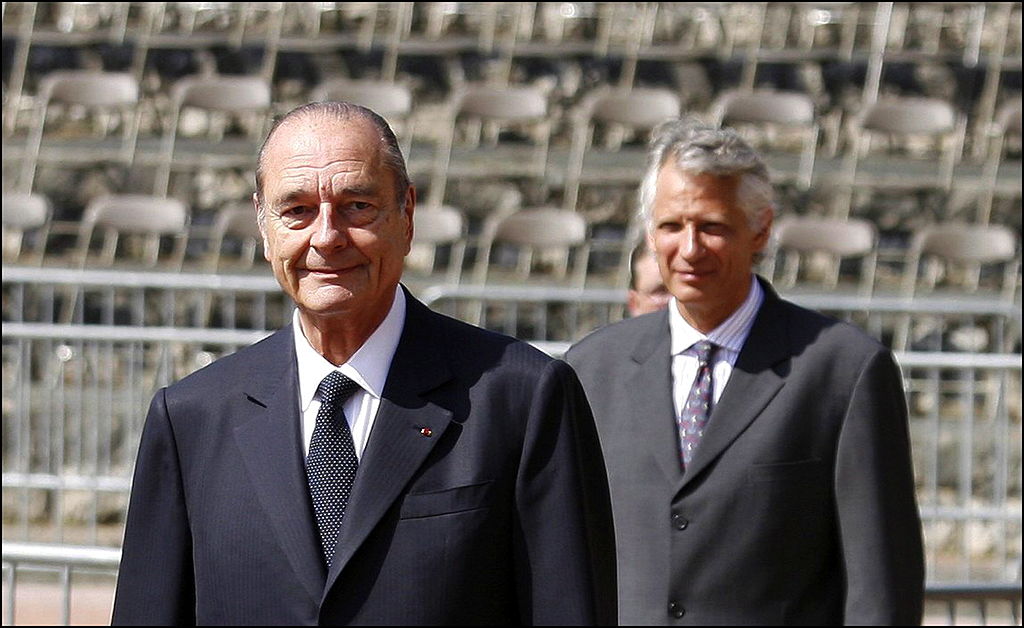

Perhaps no one witnessed so closely that era as Dominique De Villepin, one of Chirac’s closest aides, who served as his chief of staff in the Elysée Palace, and then as his Foreign Minister, where, on the floor of the United Nations in 2003, he famously told the world that Chirac’s France would not go to war against Saddam Hussein. He would go on to serve as Prime Minister of France from 2005 to 2007.

De Villepin spoke to TIME on Friday about his memories and impressions of the leader he calls “a man of history.” The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

TIME: How do you think France will most remember Jacques Chirac?

De Villepin: He was very deeply rooted in French history, France culture, and a vision of France looking at the world. He had a really deep understanding of the people and at the same time he thought that France had something special to say to the world, that France was committed to give answers in an independent way taking into account the different challenges of the world.

For Americans, probably the thing they will remember most about Chirac is France’s decision not to join the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. What was that moment like for Jacques Chirac? Was he angry and frustrated?

He really tried to convince George Bush that he had an opportunity to go with the U.N. But progressively we found out that the real objective of the Bush Administration was regime change. So when Chirac realized that he thought it was important to show to the world that the United Nations should not embark without any legitimacy. He thought the risk of a division between the West and the Muslim world was very high, and that France had a role to mediate between those two worlds.

Unfortunately after 9/11 the Bush Administration thought the best way was to use military intervention. That is where you come to Jacques Chirac as a man of memory, a man of history, a man of full knowledge of the Arab world. By 2003, we already knew that Afghanistan [France sent troops in Afghanistan after 9/11] was not the success that the international community was awaiting. We knew from Vietnam that military intervention could create a disaster. We knew as French that in Algeria also military intervention was not the option.

Contrary to many other leaders, Jacques Chirac had personal experience of war, of fighting in the Algerian War during the 1950s. That made a huge difference in terms of his personal experience and the experience of some other leaders.

Were you with him at the moment of the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001?

I was the one who informed him. He was in Rennes, in Brittany. He was there to deliver a speech on agriculture. I called him and told him about the attacks on the [World Trade Center] towers and the Pentagon. He decided to come back as soon as possible to Paris, and went to the American embassy and delivered a speech of friendship and support to the U.S. He decided he had to be the first one to go to the U.S., to go to New York eight days after the attacks to testify to the friendship and solidarity of France and the world to the U.S.

How did he respond when you broke the news to him?

HE? felt very strongly the solidarity with the American people. He understood very deeply how the world was going to change. That is why during the 2003 crisis [the invasion of Iraq] we had really tried to persuade the U.S. that facing such challenges, the response should not be war. We were entering into an era of instability, of violence, and that it was not going to solve the problem, but on the contrary would make it worse.

But you never doubted going to war in Afghanistan?

Military intervention without a very, very strong political vision and a strategic vision, gives the opposite of what we want and expected. [By 2003] we were seeing in Afghanistan the damages of such policies. That convinced us that this was not the option in Iraq.

What was the atmosphere like behind closed doors between President Chirac and President Bush?

It was a very difficult period. This was a very tense period, with strong words coming from the Administration, strong decisions on economic and military decisions. But Chirac always tried to show that he was trying to avoid instability, and that the U.S. was making a mistake, and that the price the U.S. would have to pay was something that was not good for any of us. The U.S. thought this was guided by our own interest, by the friendship with Saddam Hussein, which was absolutely not the case. We thought it was very clear there was no chance of a positive outcome of any kind of military intervention.

What did Chirac make of Americans calling the French surrender monkeys? And all the talk of Freedom Fries?

Chirac had spent a lot of time when he was young in the U.S. He knew the culture. He loved the U.S. The same for me, being educated partly in the U.S. We understood that the suffering and pain that American people and the U.S. and the Administration from 9/11 explained the emotional reaction towards France. But we thought that the moment would come when this Administration will understand that France was not motivated by bad reasons.

Your famous speech at the U.N. in 2003, was it crafted closely with Jacques Chirac?

We had daily discussions. We were on the line so much. There was not a single difference between what he felt and what I felt at that time.

People always talk about Chirac’s wit, his blunt comments. Face to face, behind closed doors, what was he like?

He had this absolutely incredible capacity to listen to people. And whenever he went into French politics on the stage, he had this appetite for meeting people, for shaking hands. He had huge pleasure in meeting people and to discuss with them and try understand their problems. He was really in politics because he loved it.

When you see the private man, he was not the kind of man always giving lessons and using his position with some kind of superiority. He was not blocked on one position. He was not a man of any artificiality. He was really somebody you could touch, you could understand, and a deeply moving human being, with strong humanity.

In 1995 Chirac became the first French leader to acknowledge France’s role in deporting Jews to the Nazi concentration camps during the 1940s. What led up to that incredibly dramatic moment?

At that time I was Chirac’s chief of staff. He felt we really had to take responsibility for it. He felt it was important for a generation. He thought that the French state – the police, the public officers that participated in these crimes – that it was important to look history in front [in the face].

It was an important factor for the young people for every generation to go forward and take the lesson for this historical crime. It was a kind of collective necessity. It was a speech where he put in a lot of work, a lot of time, and I was there when he delivered the speech. It was a really moving moment. Most of the people were not prepared for him going so far. But when he felt something was not right, he said it very loudly.

Chirac was very close to leaders in Africa who were dictators. He was friends with Saddam Hussein. He was friends with Vladimir Putin. Was this a matter of politics, or how do you understand it?

I think it is better not to make the confusion [with] having relations with everybody. Chirac’s vision of foreign policy is that being pragmatic was important. You cannot act for change, you cannot contribute in resolving crises if you cannot speak to everybody. Behind this was a very strong vision that France has to have always a diplomacy of initiative, a diplomacy of openness. And that to be efficient we need to talk to everybody. He believed there was always something to be done to take into account the other party’s position even if the other party was responsible for bad policies. Never put anybody in a corner where you cannot make any kind of change.

Jacques Chirac never agreed with the idea of regime change. He believed in respect of sovereignty of different positions means you should not force them to change. You have to do it through ways in which they can be understood, certainly not to use force to impose democracy, because then you create a situation of crisis which is much more complicated for the world to resolve.

What do you think Chirac would make of Europe today, with Brexit and the rise of the far right?

He had a very national approach to many of the world issues. Most of all he understood that to have Europe working well, there was one key condition: To have France and Germany working together. The relationship between [then] Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder and him was so close that we had a very strong impact on Europe. The vision was that Europe needed a strong Franco-German relationship.

What would he have made of President Trump? And if it had been President Trump rather than President Bush, how would he have gotten along with a man like Donald Trump?

I’m a trained diplomat, and there are many things that I can do, but science fiction is not part of my ability.

Jacques Chirac believed the U.S. were allies, the U.S. were partners, the U.S. were friends. He would want to show that solidarity is a better response. And he would have wanted to convince the U.S. that being together in a dangerous world creates more capacity to go forward, facing climate change, the situation in Iran, the situation in North Korea, the disaster in the Middle East, and the crisis in Africa. I don’t know how much this would have helped.

It feels like Chirac represents a France that no longer exists in many ways. He was not concerned about hiding his colorful personal life, for example. [Chirac was reported to have several affairs outside his marriage.] Was he the last of a particular kind of leader in France?

I am not sure. Jacques Chirac had a long career, a very long vision of history. He did not see problems with a six-month delay. That is part of a traditional culture, a capacity to look at problems through history, through geography, through culture. Not only from one angle.. I think that is still something very French, if you see what President Macron is trying to do with Iran, the willingness to try everything, to put together different options. You should look at the world not with preconceived options but asking questions. That is still very much alive, the idea that France has to be a country of balance. Look what we are trying to do on climate change. To never lose hope in finding new ways.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com