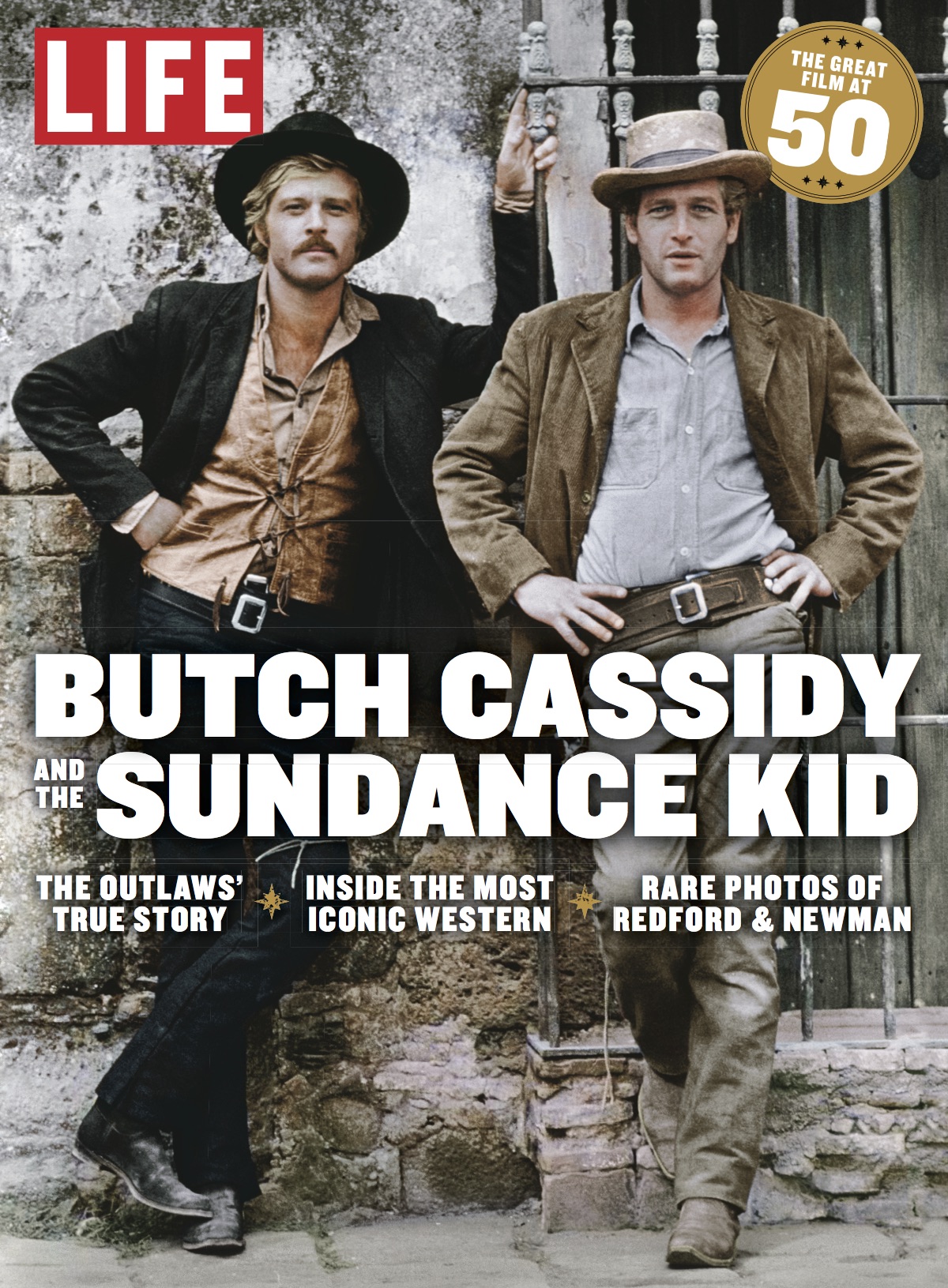

The following feature is adapted from LIFE: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid—The Great Film at 50, now available at retailers and on Amazon to mark the 50th anniversary of the the Hollywood classic, which premiered on Sept. 23, 1969.

Just after two in the morning on June 2, 1899, two men carrying lanterns flagged down the Union Pacific Railroad’s No. 1 train. Engineer William Jones, assuming the pair had come to warn him that the bridge near Wilcox, Wyo., had been washed out, braked the engine. Two men wearing masks then hopped on board and ordered Jones to cross the bridge. When the engineer didn’t move fast enough, he was coldcocked with the butt of a Colt revolver.

After the train passed to the other side of the wooden trestle, the bandits blew up the structure. Then they uncoupled the passenger cars. At that, four more villains climbed on and advised the passengers that no one would be harmed as long as they stayed calm. When the outlaws made it to the mail car, clerks Robert Lawson and Burt Bruce didn’t open the door fast enough, so it was blown off. The gang found little of value, so they headed to the express car. Cowering inside was messenger Charles Woodcock, who, despite his fear, refused to unlock the door—so the robbers blew it wide open, demolishing the side of the car. Though dazed from the explosion, the resolute Woodcock wouldn’t reveal the safe’s combination, so the robbers set off another blast—and made off with $50,000 in cash along with jewelry, gold and diamonds.

The Sundance Kid led the heist. While the head of the gang, Butch Cassidy, wasn’t there, he had orchestrated the robbery and arranged horse relays to help his men get away. So by the time engineer Jones arrived in Medicine Bow, Wyo., and shot off a telegram—“First Section No. 1 held up a mile west of Wilcox. Express car blown open, mail car damaged. Safe blown open; contents gone”—the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang had vanished.

As infamous outlaws, Butch and Sundance had come quite a way from their humble, God-fearing origins. Cassidy was born Robert Leroy Parker on April 13, 1866—the year outlaws Jesse and Frank James robbed their first bank—to a family of devout Mormons. His mother, Ann, and father, Maximilian, were early settlers in Circleville, Utah. Maximilian toiled long hours as a farmer, while Ann homeschooled her brood of 13, teaching them fundamentalist values. As the oldest, much work fell to Robert; at 13 he headed to a nearby ranch to make money for the family. There he met a horseman, cattle rustler and gambler named Mike Cassidy. Cassidy was not a churchgoing man, and he taught Parker many of the ungodly things he knew—including how to make a better, if distinctly dishonest, living.

At 18 Parker abandoned his family’s impoverished land. In the summer of 1884 he landed in the mining boomtown of Telluride, Colo., where gold fever filled the bars, gambling dens and brothels. By then, though, the major gold claims had been staked, so Parker found a job hauling ore down the mountains. Looking for an easier way to make a greenback, he noticed the town’s San Miguel Valley Bank. Parker cased the building and figured out when the money came in and left. Then, on June 24, 1889, with three others, he waited till most of the staff was gone, and made off with $20,000.

Parker not only planned the heist, but knowing they would be chased, set up fresh horses along the escape route so his team could race away and avoid capture. Now a wanted man, he feared embarrassing his mother, so he changed his name to George Cassidy in honor of his mentor. And because he had once worked as a butcher, he soon started to go by Butch Cassidy. In 1894 he landed a two-year stint in prison for possessing a stolen horse.

Cassidy wasn’t the only one aching for a new life. Harry Alonzo Longabaugh came from a family of strict Baptists in Phoenixville, Pa. Born in 1867 to Josiah and Annie Longabaugh, he had worked on the canals, and at the local library he checked out pulp novels and probably read about the exploits of Buffalo Bill, Jesse James and Calamity Jane. For a restless youth, the frontier offered adventure, and like many others he heeded the words of New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, who wrote, “Go west, young man.” In 1882, at the age of 14, Longabaugh found work on his cousin’s Colorado ranch. There he learned to be a cowboy, and ended up laboring all over Wyoming and Montana. But when work dried up, he turned to petty crime, and at 20 spent a year in jail in Sundance, Wyo., for stealing horses. When released, he called himself the Sundance Kid.

The west has a history of men who, like Butch and Sundance, reinvented themselves as they sought to make a dishonest living. Their opportunities increased in May 1869 when the Central Pacific Railroad linked up with the Union Pacific. With the ceremonial driving of a final golden spike at Promontory, Utah, the train lines joined the East and the West Coast, creating cross-continental travel, turning trains into easy targets and giving birth to a golden age of Western banditry.

There were a lot of criminals out there eager to take advantage of the opportunities, some famous like Sam Bass, the James boys and William “Billy the Kid” Bonney Jr., and others now lost to history. They and their gangs searched for easy pickings, and many found refuge in a vast series of hideouts along the Outlaw Trail, which stretched from Montana down through Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, and into Texas and Mexico. In the mid 1890s, on the Outlaw Trail, Cassidy and Sundance first met. The two men developed a close friendship and learned to trust each other. Butch was the gregarious and charismatic one. The handsome Sundance proved to be quieter, and his quick draw earned him a reputation as the best shot around. On Aug. 13, 1896, Cassidy led a bank robbery in Montpelier, Idaho, making off with between $5,000 and $15,000. According to local lore, five days later, he called together more than 200 like-minded outlaws at Brown’s Hole and called on them to pool their talents and form a “Train Robbers’ Syndicate.”

The organization was really a loose confederation of groups with fluid memberships. Butch’s shrewd leadership skills made him a natural chief of the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, some 20 colorfully named bandits, desperados and good-for-nothin’ characters. Butch and Sundance’s group was different from the others. Butch stressed the use of kind persuasion with the hint of deadly repercussions. And while Butch took the lead in planning, he welcomed the others’ thoughts and insights as they plotted out which banks, mining companies and trains to rob.

The outlaws kept busy as they headed out in assorted teams. In an April 1897 daylight robbery at the Pleasant Valley Coal Company in Castle Gate, Utah, they snatched $7,000, cut the telegraph wires and raced away. Two months later, they robbed the Butte County Bank in Belle Fourche, S.D., but made off with only $87. On July 14, 1898, the gang hit Southern Pacific passenger train No 1. When a messenger refused to open the express car, the outlaws detonated dynamite outside as a show of force. The messenger quickly complied, and Cassidy’s boys gathered up some $26,000 in cash and jewelry. And in June 1899 the gang held up Union Pacific No. 1—the train Woodcock worked on; The Rawlins Semi-Weekly Republican reported that after placing an excessive charge on the safe, the gang “wrecked the car, blowing the roof off and sides out, portions of the car being blown 150 yards.”

On Aug. 29, 1900, the gang robbed Union Pacific train No. 3 out of Tipton, Wyo. When the man inside the express car refused to open it, they set dynamite. Only then did the door slide open and reveal the unfortunate Woodcock from the Wilcox heist. The outlaws pilfered about $55,000, and as they left, Cassidy reportedly said, “Goodbye, boys.” In September 1900 they slipped into Winnemucca, Nev., and robbed the First National Bank of $32,640.

Butch & Co. hunkered down on the Outlaw Trail, squandering their earnings on drink, cards and women. A popular spot was Herb Bassett’s ranch along northern Utah’s Green River. Bassett had a large library, and let Cassidy look through his books. He also had a daughter, Ann, who became involved with Cassidy. Sundance, meanwhile, had been seeing Ethel “Etta” Place, whom he probably met at Fannie Porter’s brothel in San Antonio. It is not certain that Place was really her last name, since it’s also Sundance’s mother’s maiden name.

But even though the Hole-in-the-Wall gang was laying low, their success drew unwanted attention. Butch’s Wyoming mug shot was circulated, and by 1898 their robberies made headlines. The Omaha Daily Bee declared CASSIDY IS A BAD MAN: LEADER OF THE ROBBERS’ ROOST GANG AND HIS ADVENTURES. TERROR TO MEN OF THREE STATES. His gang started to assume a mythic stature—all crimes were laid at their feet—and earned coverage in the Eastern press and inclusion in the pantheon of dime novels. “They were lawless men who have lived long in the crags and become like eagles, shunning mankind, except when they swooped down upon some country bank to rob it at the point of a pistol, or rode out on the range to gather in the cattle or horses of other men,” reported the New York Herald. Many even saw them as heroes; a report that Butch returned money to a widow following a bank robbery earned him the nickname “Robin Hood of the West.”

By then, the West was changing, and railroad executives, mining kings and others wanted to halt the attacks. The June 1899 Wilcox robbery prodded the Union Pacific to track down the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang. The railroad put out a reward and hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Pinkerton’s motto, “We never sleep,” offered a clue to their approach, and in no time their detectives and police scoured the West for the group they dubbed the Wild Bunch.

Read more in LIFE: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid—The Great Film at 50, available at retailers and on Amazon.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com