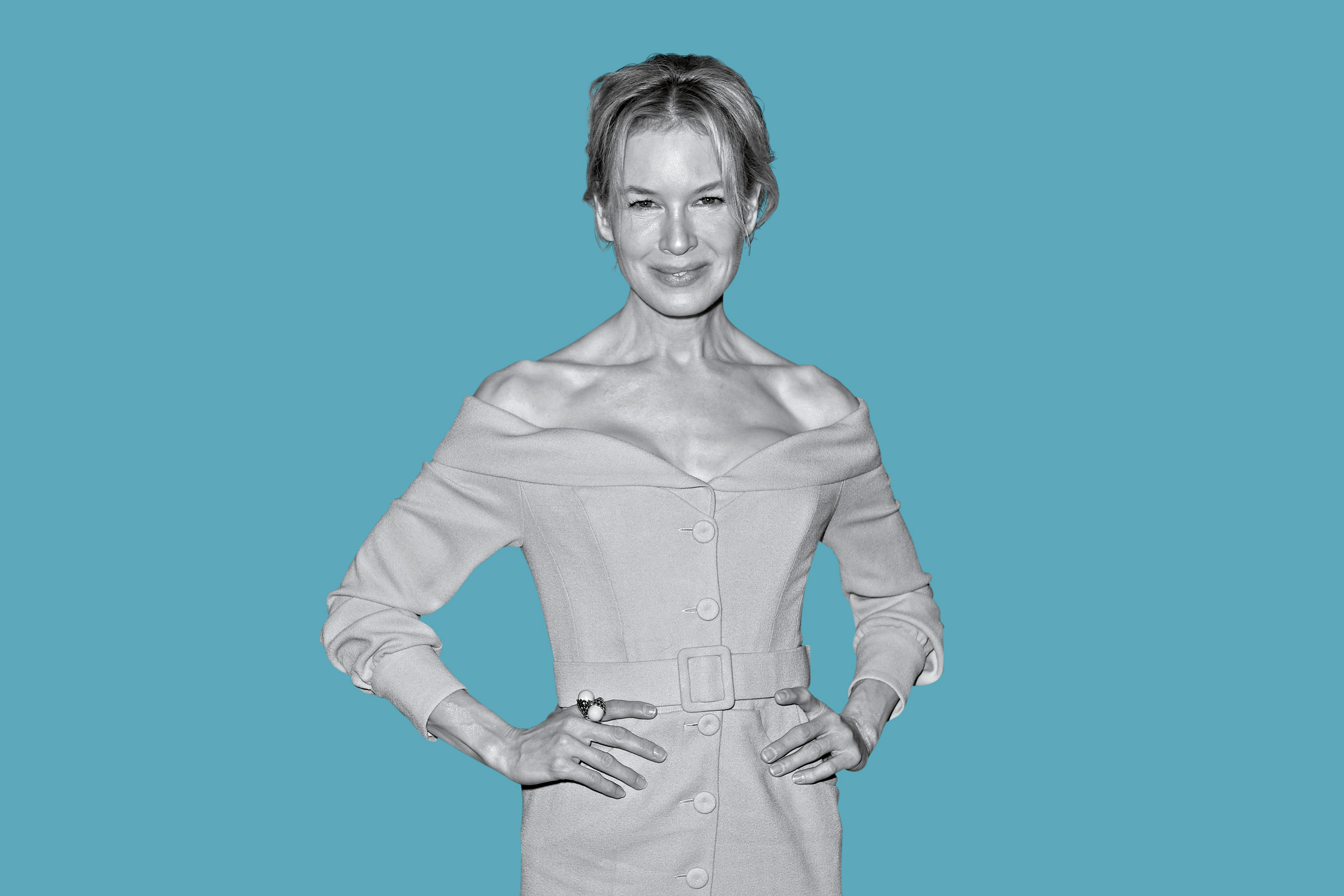

The Oscar-winning actor on playing Judy Garland, how Bridget Jones holds up and the public scrutiny of women.

You spent two years preparing for the film Judy. What stood out as the most important thing to capture about Judy Garland?

What struck me was, despite the tragic circumstances and how they were portrayed on the public record, she never stopped hoping. She was a joyful person. She didn’t strike me as a tragic figure at all. She seemed heroic in her determination to carry on and her belief that things would get better.

In the film, her fans feel they know her, but she doesn’t appear to feel known by them. Is there a certain loneliness that comes with fame?

I’m sure it’s different for everybody. I suppose it depends on how much of your public persona and professional responsibilities consume your time vs. how much time you spend focusing on the person behind the public persona.

Is it different preparing to play a real person?

Absolutely, because there are parameters that are the historical record. But having an experience with that myself, and being the subject of certain reporting, I try to be judicious in looking at it and consider the source and remember that whatever is out there is always through [the lens of] someone’s personal agenda or their own damage.

She once called herself “the queen of the comeback”–[Paraphrasing Garland]

She can’t go to the bathroom without them calling it a comeback!

There’s a narrative around the movie that it’s a comeback for you, just a few years after you returned from a six-year hiatus from acting. How does that word sit with you?

I don’t think about that kind of stuff. However people interpret things, it’s none of my business. I don’t read things. I’m not on social media.

Your break coincided with an age when many women find that juicy roles start to dry up. Do you feel like you skipped that period?

Maybe. Or maybe the industry changed and there are more outlets for material. There will be an audience for stories about women of every age if someone creates them. There’s always been an audience for different kinds of material, it’s just limited in terms of what the business model seemed to allow. So as that’s changing, the range of stories is expanding. Escape at Dannemora and Patricia Arquette out there doing her thing, Patricia Clarkson doing her thing, Julia Roberts doing her thing, the list goes on.

I rewatched Bridget Jones’s Diary recently. It’s different watching Bridget’s flirtations with her boss, Daniel Cleaver (Hugh Grant), in the #MeToo era. Is it fair to judge past movies through the lens of today?

I can’t remember how much of it they were trying to conceal, because it was taboo. It wasn’t something they were trying to advertise. Maybe there are just different consequences hanging in the balance in 2019.

In 2016 you wrote an op-ed criticizing tabloid scrutiny of women’s bodies, including your own. Has anything changed since then?

That’s a big question. I think there’s a consciousness about it that might be a little bit different. What do you think?

We have a long way to go.

Maybe. But these are institutionalized, social behaviors that are reinforced through generations. So inevitably it’s going to change if you have women raise their children with an expectation that they be treated differently. As we go forward and we make certain realizations about the way we conduct ourselves in society, then the change comes. But I expect that it will take a minute.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com