As the fall season begins, many women across the United States and the world are getting ready for “tights season,” the moment when the cooler weather means it’s time to pair skirts or dresses with a little extra warmth on the legs. Some may be looking forward to the fall fashion opportunities, and some dreading sagging knees or the necessity of dabbing clear nail polish on runs. But when tights first became a wardrobe staple, they signified something that went far beyond a simple change of season: freedom.

History books credit Allen E. Gant with creating pantyhose — or “Panti-legs” — in 1959. The idea came to him while on an overnight train to North Carolina with his pregnant wife, Ethel Boone Gant, when the two of them were returning home from the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. Ethel told her husband this would be the last trip she would be going on before the baby came, since managing the combination of thigh-high stockings, girdle and garter that women were expected to wear out was becoming too uncomfortable. When they came home, Gant was inspired and asked his wife to stitch a pair of stockings onto panties and try them on. She didn’t hate them, so Gant took the prototype to the clothing mill where he worked and found a practical way to knit pantyhose on hosiery machines with non-stretch yarn.

The process was one of trial and error. “At first, they’d come up to your chin,” seamer Margaret Minor told the Asheville Citizen-Times in 1989. “You could get your whole body in it — that’s how stretchy it was. They they learned to put some control into them so they would fit at your waist.” The pantyhose also felt like an odd gimmick, since hose had previously always stopped at the thigh. “It was quite funny to try them on and look down at yourself and see hose coming to your waist,” Minor said. “It was kind of a funny sight at first.”

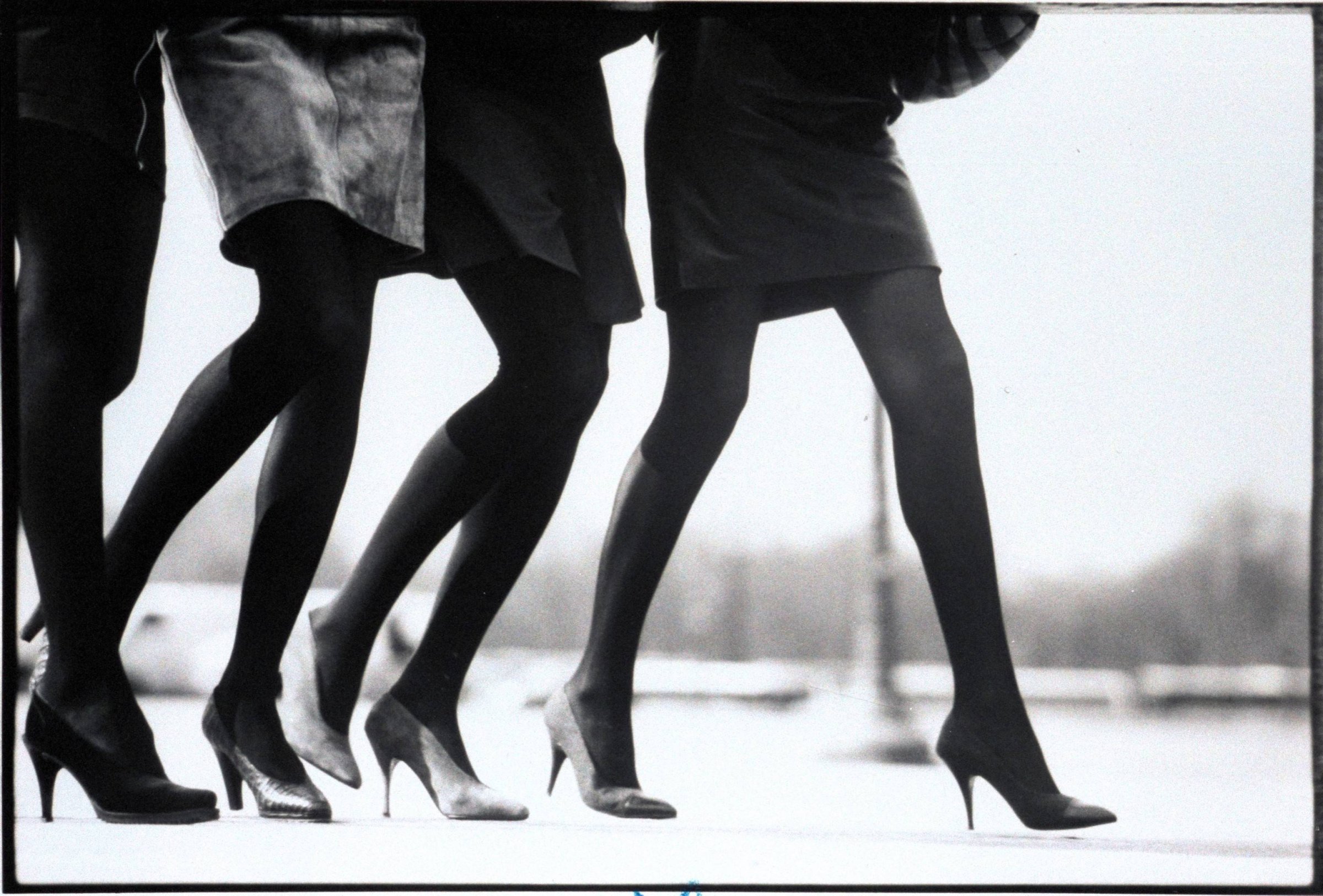

But while the new pantyhose were convenient, it wasn’t until the rise of miniskirts in the mid-’60s that tights started to really become popular. Once models such as Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton put on their minis and added tights, young shoppers rushed to department stores to get their own pairs. Part of the reason for that was because of the minis’ short hems, as it wouldn’t look proper for a garter belt to peek out from under a short mini.

“Prior to the mini, it was expected that women would wear the full gamut of foundation garments and slips. Tights, as much as the mini, were a gesture of freedom and one that pointed towards youthfulness,” Moya Luckett, a media historian and co-editor of Swinging Single: Representing Sexuality in the 1960s, explains.

While tights were convenient, they also helped to tell a new story about young women’s place in society. Young women dressed like mini versions of their mothers in the ‘50s, but the ‘60s brought on clothes that belonged distinctly to a new generation. In the 1960s, the average American age of marriage for women was about 20, and the average age of having a baby was 21, but the young women participating in the era’s revolutionary wave often rejected the expectation that they would become wives and mothers that early. Their wardrobes reflected that idea by taking on a girlish spin.

One group in particular seized on the youthful look: the Mods. Newspapers described the Mods as “post diaper,” “dressed like fugitives from kindergarten” and “cartoon versions of third-graders.” One designer, who was fed up with grown women wearing childish silhouettes, told Newspaper Enterprise in 1965 that the Mod girl “looks as silly as though she had stuck a lollipop in her mouth.”

“The Youthquakers follow another road. They repeal female sexuality by rolling back the years to pre-puberty and even younger. How could a chap imagine making a pass at a girl-child in rompers? The cops would come running from four directions,” The Daily Standard reported in 1966.

But that was part of the appeal: the Mod look, including the tights, allowed women to extend their adolescence, the space between childhood and adulthood.

No one knew this better than Mary Quant, the London-based designer who popularized the look. “When I was 13, I sat down and had a good cry about the business of growing up. What really unnerved me was the awful realization that grown-up dressing was grotesque and drab. I wanted to evade the entire issue of adulthood by wearing childlike clothes forever,” the mother of the Mod Movement told The Times-Tribune in 1976. “When I was seven, I went to dancing class and the most beautiful girl there had bobbed hair with bangs, wore black tights and a pleated mini skirt. It was the way I wished I looked.” Quant took the tights-and-mini uniform from her past and re-imagined it for young women’s wardrobes. The tights came in Crayola colors, playful prints and girly embellishments, capturing an innocent aesthetic.

“If you go back 45 years ago, the idea that marriage was the end of a certain kind of freedom was in fact politically and legally true. It was the end of a certain kind of agency. So the mini skirt paired with tights could be understood in that context — it was available to women to carve out a space for a kind of personhood that was pre-marriage,” explains Marjorie Jolles, a Women’s and Gender Studies Associate Professor at Roosevelt University.

Because of that, tights became part of a message of anti-establishment and looking towards the future. “The Mods very much believed they were embracing their own kind of modernity, that they were the ones that were going to design the future of fashion, that even the mere structure of clothing was going to be done differently. These guys believed they were the new generation of fashion, and that their fashion embodied modernity that their grandmothers’ did not. They represented a new freedom from the past,” Deirdre Clemente, a historian of 20th century American fashion, explains. explains.

Squeezing into girdles and the societal expectations of femininity that came with them seemed outdated, and so young women reached for something different. “The collective sigh heard ’round the world in the early sixties was millions of women removing these cumbersome under-pinnings for the last time and stepping into a new, sleek freedom,” the Boston Globe reported in 1972. “The Great Underwear Revolution had begun.”

Not that everyone was included in the revolution. “For a range of reasons, non-white girls and boys aren’t granted the same kind of childhood that whites are; a childhood that is largely coded in terms of innocence, purity, virtue,” Jolles says. “So ‘girly’ doesn’t work on non-white bodies the way it works on whites, in that it cannot send the same signal.”

Nevertheless, the 1960s was the decade that put the words “generation gap” into society’s vocabulary, and girlish accents helped to create that wedge. “Each of these looks was a by-product of social discontent — a flaunting of rebellion against tradition,” The Daily Mail reported in 1969.

Clothing trends aren’t reflective of change, but rather constitutive of change. By wearing tights and adopting a childish wardrobe, women created their new reality.

Ann Tucker, a 19-year-old secretary in the U.K., told Parade in 1966: “A girl looks around at her Mum to see what life in England has done to her. And she doesn’t like it. Least of all I don’t. We still have the double sex standard here, and I don’t buy it. I want a different world for me and my children. The adults won’t give it to us, so we’ve got to make it for ourselves. We’ve got our own dress, our own music, our own heroes, our own standards.”

Sagging knees and runaway snags might feel like an inconvenience nowadays, but they once signaled a shift towards greater freedoms. Think of that the next time you get a hole in your toe.

Correction, Sept. 25

The original version of this story misstated Moya Luckett’s role in the book Swinging Single. She is a co-editor of the book and author of one of the pieces it includes, not the author of the book.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com