Several years ago, I went off to research a remarkable community that has a history of sheltering vulnerable outsiders. I went looking for clues to how a community like that operates. I hoped I could learn some general lessons there about how groups of people can resist the call to violence, exclusion, and bigotry.

The tiny plateau of Vivarais-Lignon, in south-central France, is well known to scholars of the Second World War. During the German occupation of France, the region’s farmers and townsfolk sheltered, hid, fed, schooled, and shuttled to safety hundreds, perhaps thousands, of war refugees—most of them Jewish, most of them children. They did this at great risk to their own lives, and they did it for years on end, not just in one great burst of heroism.

As rare and extraordinary as this collective rescue was, I quickly learned that the Holocaust was not the first time that the people of this community risked their own safety to shield others from harm. They did it off and on for centuries: during the religious wars between Catholics and Protestants, during the French Revolution, and during the Spanish civil war, among other conflicts that produced waves of displaced persons and trans-border refugees.

I saw in this place a kind of example of what we would hope all communities could know how to do: protect those in need, take care of them, send them toward new lives in safer places. As a social scientist and anthropologist, I knew how to analyze this kind of collective action. My training taught me how to study the ways people conceptualize and then interact with outsiders. I anticipated that there would be hints there, even today, about what made this community do something so remarkably rare—collectively risking their own lives, time and again, for the sake of strangers. I thought that if I could find these social practices, pinpoint them, maybe I could learn from them—take on board the technology of peace that these people seemed to have gotten so right.

The lessons there were manifold. And they began with a surprise.

Not long after I first arrived, I discovered that the plateau had not only a history of protecting people, but that its inhabitants were also doing so today. Asylum-seekers were flocking there, from central Africa, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and other strife-torn regions.

So, I got to see how strangers were treated in real time. Local people opened their homes, shared their knowledge and resources, and helped families rebuild their lives. I saw how strangers were treated not as examples of certain ethnic groups or religious groups or national groups, but simply as human beings, full stop. That is, humanity was something that everybody shared—locals and newcomers alike—no matter what they needed, no matter how the course of their own lives had unfolded.

There were other social practices that mattered there; I used the many tools that I’d accumulated over the years as an anthropologist to look closely at how hospitality worked, how children were agents of the broadening of social circles; how to see, even in reserved provincial temperaments, the manifestation of great generosity: quietly sitting with newcomers, in their anguish and hope; knitting clothing for babies born in flight; opening homes—breaking bread, sharing hearths.

The social lessons in the Plateau were vividly on display. But it turned out that the story of the Plateau Vivrais-Lignon had a personal side to it as well—something I never could have imagined when I began the journey.

Many years ago, an aunt of mine had given me a book called Lest Innocent Blood be Shed. She told me the story in the book was somehow related to our family. I took note, but didn’t quite understand the connection. Years later, when visiting the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, I saw an entire exhibit about the wartime efforts in the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon. It featured the family name of my great-grandfather’s second wife—Suzie Trocmé—who had been a kind and lovely presence in my childhood, and who had once invited me to visit her in France.

As I delved into the history of the plateau, I learned that Suzie Trocmé’s family was in fact very closely tied to its story of rescue and resistance.

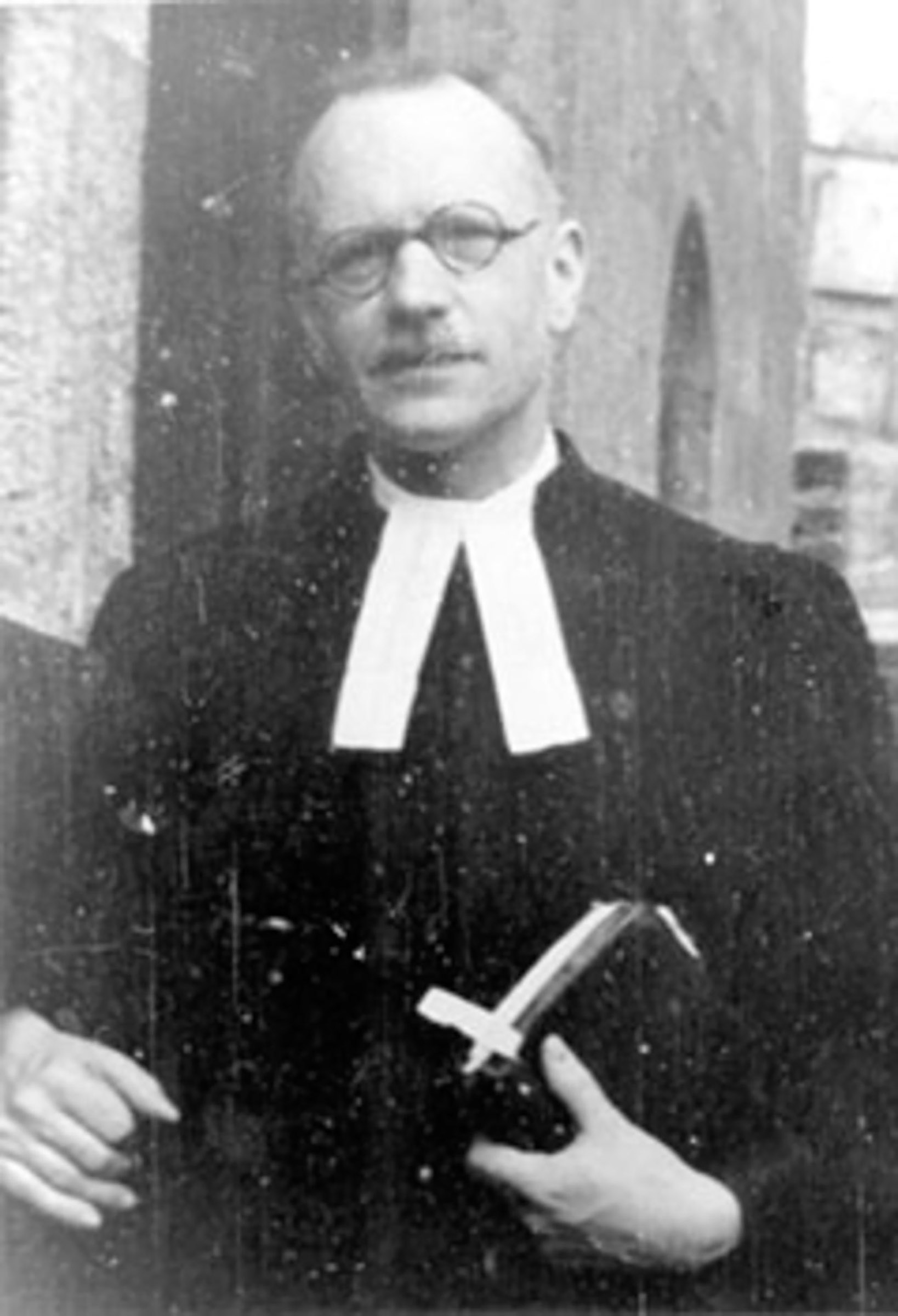

Daniel Trocmé—Suzie Trocmé’s beloved younger brother—was a young man from a family of prominent educators. Born in 1912, he studied at France’s best schools, in the brightest circumstances, and had before him a predictable life path that would have brought him into the highest echelons of French society and culture.

During the political turmoil of the 1930s, Daniel started questioning the life-course that had been laid out for him by his family. He traveled extensively—across Europe, around the Middle East—and began to doubt the certainties that he was raised in. Perhaps there were many civilizations and many ways to God, he came to believe, rather than just one ascendant religion or one version of civilization. His family worried about him.

In 1942, as the war in Europe raged, he received a request from a cousin who was then working as a pastor in the remote region of Vivarais-Lignon. That cousin—André Trocmé—was already making a name for himself in his effort to help Jewish children who had found themselves taken to French concentration camps. He and others in the remote plateau set up homes for these children where they could be fed and kept safe. André needed help with the effort. He asked his young cousin Daniel if he could come to the plateau and help run one of the homes for children.

Daniel did, and it turned out to be a fateful decision. Taking care of refugee children was exactly the kind of meaningful life he had been looking for. But the price was extraordinary. When the Gestapo launched a raid, Daniel refused to flee for his own safety, and remained alongside his young charges. He was arrested, deported to Poland, and then died in a Nazi camp there.

Daniel’s story became a kind of lodestar for me. For all my social scientific analysis—trying to figure out what made the plateau and its people so expert in doing the right thing—I realized that none of this could tell me how I myself would behave when put to the test. I was haunted by the thought that no matter how hard you prepare, no matter how good you think you might be, you simply don’t know the decision you would make when confronted with Daniel’s choice: to save himself, or to stay behind and shelter others.

In the course of my work on the Plateau, Daniel Trocmé, as an individual—a “seeker”—became more and more central to my story. I wanted not only to understand what a group did, in theory, but how an individual, faced with the worst possible times, might make the right decision.

I wanted to empathize with that moment of decision, to really understand it. I wanted to put myself on the hook. I wanted to entertain the terrifying possibility that I—well trained by science or not—might make the wrong decision.

The farther I went in my journey, the more I saw that I was no longer capable of making neat boxes where I separated science and analytics from the question of my very own heart, my very own soul. I see now that you can prepare and prepare, but the real work might be in investing each moment you live with meaning. Like Daniel, you never know when the sky will open up, or men with guns will descend, or a stranger will stand battered and afraid at your door, you will be put to the test.

But it seems to me now that people and entire communities can learn to be good in a couple of ways. They can learn when growing up, by habit, that this is how you treat strangers. This is how you handle your own identity—your sense of clan, or tribe, or nation—and make it at least equal to the needs of strangers. You can take as a given that you share a common humanity with them. You can learn those things so well that acting otherwise would be unthinkable, and the censure for acting in such a way would be great. The Plateau gave its inhabitants, over many centuries, the gift of this habit.

Not all of us can grow up in a society like that. It seems to me now that there is another path to that kind of goodness.

And that is through having been moved, having been catalyzed to do good, in a moment. It is a kind of magic when it happens, that instance when you literally turn the face of a stranger into something familiar, the face of a friend—an alchemy of recognition that Daniel experienced and that I’ve seen people on the plateau today live today, in real time, in their own lives.

How do you do that? You learn to love. You can use your religion to help you if you want (all religions, I believe, have that message at their core). Or you can use whatever other poetic, aesthetic, or humanistic tools you have. When you fall in love, you overcome your own fear.

Places are good not because of magic soil or enchanted water. The plateau isn’t good for those reasons. It’s because the people who have lived there in the past, and who call it home today, have learned something about the irresistible call to do the thing that they have carved in stone on the church at the center of one of the villages: AIMEZ-VOUS LES UNS LES AUTRES. Love One Another.

It’s a call we can all respond to, a tocsin that can sound for us all in our own terrible times: There is no them, only us. There is no then, only now.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com