Archimedes had geopolitics about right when he declared “Give me a place to stand, and I will move the Earth.” The U.S. military has little place to stand when it comes to Russia’s threats against neighboring Ukraine, giving it little leverage when it comes to changing what’s happening on the ground there. That fact has led to outrage among congressional Republicans, who want President Obama to do more to thwart Russian President Vladimir Putin’s expansionist goals.

It also has triggered shrugging shoulders among U.S. military officials who concede there is little they could do militarily to stop Putin—even if Washington wanted to try. Pentagon officials say the Russian forces now staged just outside Ukraine could invade and seize the eastern half of the country in as little as three days.

Instead of threatening a military response, Obama and his troops have unleashed volleys of rhetoric threatening tougher sanctions as a way of trying to deter Putin, as well as sending “signals” designed to make him think twice.

In recent days, the U.S. military has:

The U.S. has drawn a red line: it will defend its NATO allies, as required by treaty, but Ukraine is on its own.

“The United States and our allies will not hesitate to use 21st century tools to hold Russia accountable for 19th century behavior,” Secretary of State John Kerry told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Tuesday. “We’re using 21st century tools, which are the tools of diplomacy, to bring people together in other countries to put sanctions in place.”

Such threats didn’t sway Senator John McCain. “What you’re doing is talking strongly and carrying a very small stick—in fact, a twig,” the Arizona Republican told him. “Here we are with Ukraine being destabilized, part of it dismembered, and we won’t give them defensive weapons.”

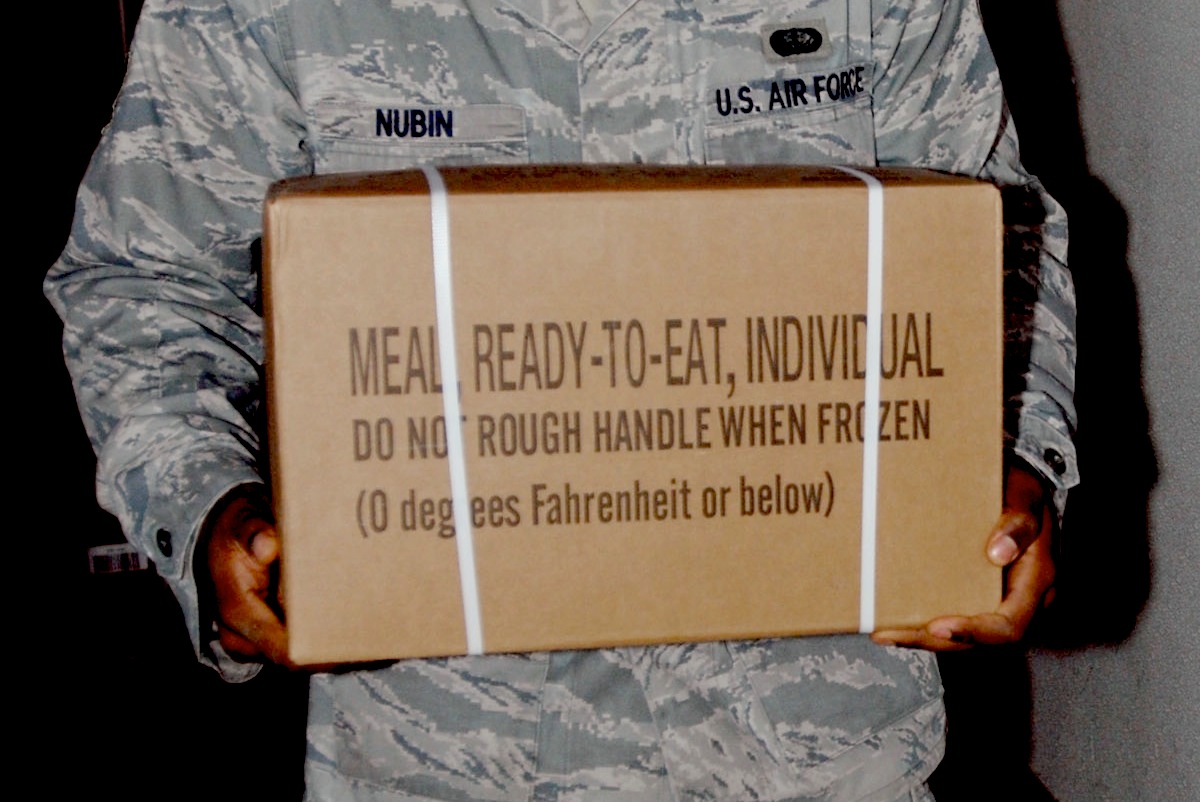

“Sending MREs is basically,” Rep. Mike Turner, R-Ohio, said at a second hearing, “expanding our school lunch program.”

“Their forces have been in the field for a very long time, and need those supplies,” countered Derek Chollet, the assistant defense secretary for international security affairs. He added that the Pentagon is trying to help Ukraine “without taking actions that would escalate this crisis militarily.”

That’s a bracing change for the U.S., which for the past generation has seen itself as the world’s lone super power, able to flex its military muscles when and where it wanted. It concedes the inevitable: if Putin, despite world opprobrium, orders the up to 80,000 troops he has positioned on the border to roll into Ukraine, neither the U.S. nor its European allies appear willing to do anything to stop him.

It’s what the military calls the “tyranny of time and distance” that makes any U.S. military intervention in Ukraine challenging. Not only are the U.S. assets needed thousands of miles away, Russian troops and weapons are close at hand. The U.S. has done little militarily with Ukraine; this year the Pentagon is providing about $4 million in military aid—$11,000 a day. A significant slice of the Ukrainian population is pro-Russian. And the U.S. public opposes U.S. military action in Ukraine (an interesting poll reveals that the less Americans know about Ukraine, the more they support U.S. military action there).

“I don’t think anybody on this committee wants to go to war with Russia over the Ukraine,” Rep. Adam Smith, D-Wash., said. “But we do want to find a way to stop them from further aggression.” That quiver of options is largely limited to stepped-up economic sanctions and international ostracism. (“Mr. Putin very much enjoys the international spotlight,” Chollet said. “Russia is finding itself more and more alone in the world, and that will have an effect as well”).

Yet even as the U.S. refrains from military action in Ukraine and objects to Putin’s takeover of Crimea last month, it agreed to cut its nuclear arsenal as part of a 2011 arms pact with Russia. “Both sides have agreed this is important,” a senior defense official told the Wall Street Journal.

Nearly 20 years ago, the U.S., Britain and Russia signed a deal in Budapest that guaranteed “the existing borders of Ukraine” in exchange for Kiev giving up the nuclear weapons it had inherited from the Soviet Union. A senior U.S. official told reporters in December 1994 that this so-called Budapest Memorandum was also important, confirming the security assurances reached earlier that year among the three nations. “You might remember the crisis in April with regard to the Black Sea fleet and Crimean questions,” the U.S. official said. “They were an important sign at that time, that both Russia and the United States were committed to the territorial integrity of Ukraine.”

But unlike Article 5 of the NATO Treaty, which obligates all 27 other members of the alliance to come to the aid of one that is attacked, the Budapest Memorandum is merely a memo. “I say this to our Western partners: if you do not provide guarantees, which were signed in the Budapest Memorandum,” Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseny Yatseniuk has said, “then explain how you will persuade Iran or North Korea to give up their status as nuclear states.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Contact us at letters@time.com