Americans aren’t sleeping well. Roughly 80% of U.S. adults say they struggle to fall asleep at least one night a week, according to a recent Consumer Reports survey. And research has found that sleep problems are also on the rise among adolescents.

While the causes of America’s sleep woes are up for debate, there’s little disagreement about America’s favorite remedy: Melatonin, by far the country’s most-used sleep aid.

What is Melatonin?

Melatonin is a hormone that plants and animals, including humans, produce naturally. The melatonin sold in over-the-counter pills is synthetic, but chemically it’s the same as the stuff the human body makes. It can, if used properly, help certain problem sleepers get to bed at night.

Research has also shown it can help combat inflammation, promote weight loss, and maybe even help children with neurodevelopmental disorders. That’s a lot to claim, though there are some studies to back up the various benefits. One 2011 review found evidence that, in children with autism, melatonin supplementation led to improved sleep and better daytime behavior. A small 2017 study from Poland found that obese adults who took a daily 10 mg melatonin supplement for 30 days while eating a reduced-calorie diet lost almost twice as much weight as a placebo group. The underlying cause might be connected to the fact that blood measures of oxidative damage and inflammation were much lower in the people who took melatonin.

“Some of the emerging science is showing that in people with higher levels of inflammation—which could be because they’re obese, or because they’re in the [intensive care unit] for a transplant—melatonin in the range of 6 mg to 10 mg may decrease markers of inflammation,” says Helen Burgess, a professor of psychiatry and co-director of the Sleep and Circadian Research Laboratory at the University of Michigan. If someone is healthy, it’s not clear that high-dose melatonin has a similar anti-inflammation effect, she adds. But it’s possible.

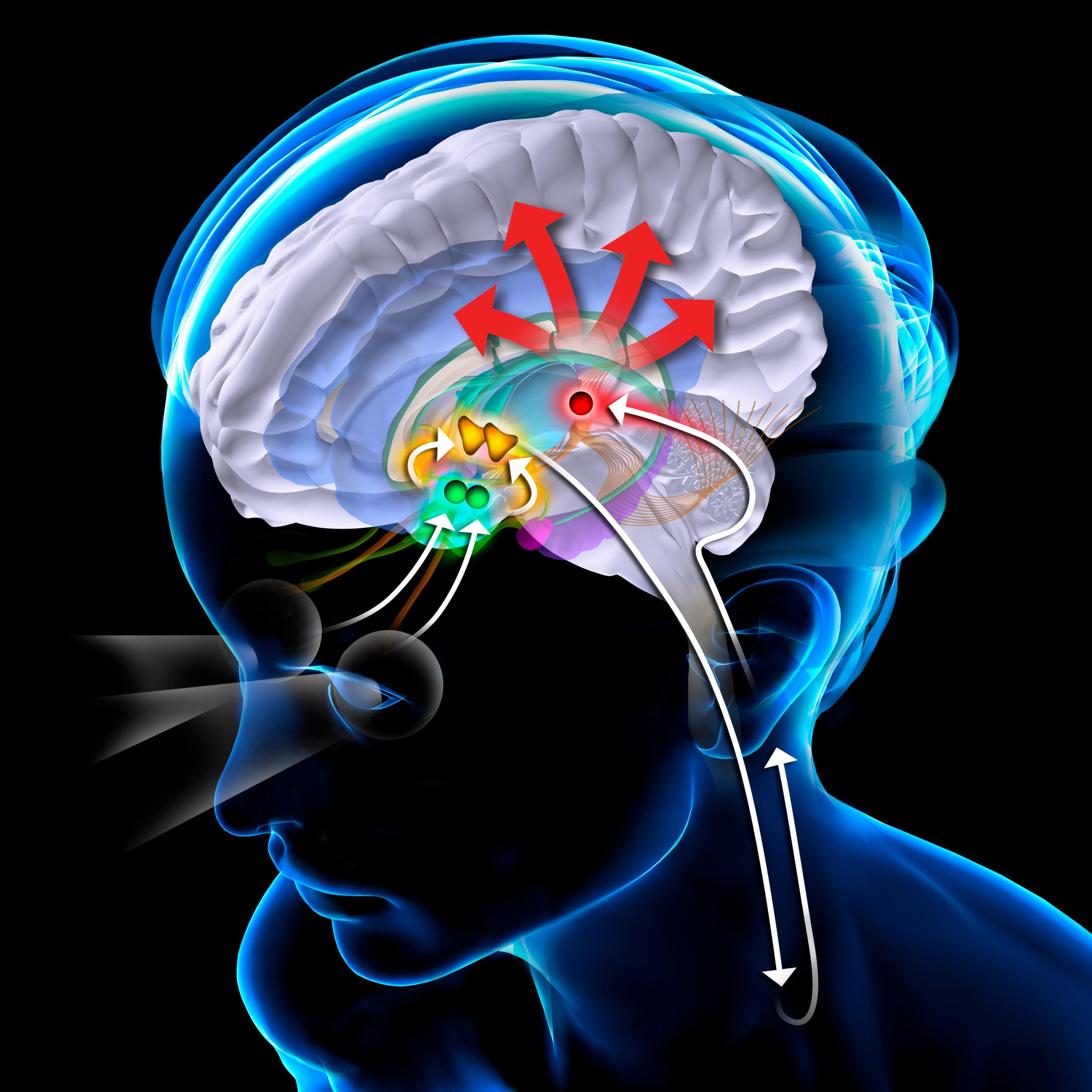

Burgess is one of the country’s foremost melatonin researchers. She says that the traditional view of melatonin is that it plays a role in regulating the body’s internal day-night clocks, which is why it can help people sleep. “But there’s a theory that melatonin’s original purpose was as an antioxidant, which is what it does in plants,” she says. This alternative theory holds that it was only later in human evolution that melatonin took on a secondary role as a biological clock-setter.

Inflammation, like poor sleep, is implicated in the development or progression of an array of diseases, from heart disease and diabetes to depression and dementia. If melatonin could safely promote both better sleep and lower rates of inflammation, it could be a potent preventative for a lot of those ills. And melatonin appears to be safe—though there isn’t much research on the long-term effects of taking it in heavy doses.

What is a safe melatonin dose?

According to Michael Grandner, director of the Sleep and Health Research Program at the University of Arizona, “melatonin is very safe if taken in normal doses,” which is anything between 0.5 mg and 5 mg.

A 0.5 mg dose may be all that’s needed for sleep-cycle regulation, and should be taken three to five hours before bed, he says. For people who want to take melatonin just before bed, a 5 mg dose is appropriate. “Some people report headaches or stomach problems at higher doses, but those side-effects are uncommon,” he says.

Still, there are other concerns. “Melatonin has an incredible safety record, no doubt about it,” says Dr. Mark Moyad, the Jenkins/Pomkempner director of preventive and alternative medicine at the University of Michigan. “But it’s a hormone, and you don’t want to mess around with hormones until you know what they’re doing.”

People with existing medical problems should discuss melatonin with their doctor before using it. While some research has found that melatonin may help treat hyperglycemia in people with diabetes, for example, other studies have shown that, in diabetes patients who carry certain genetic traits, melatonin may interfere with glucose regulation. It’s these sorts of contradictory findings that give experts pause when it comes to issuing melatonin a full-throated endorsement.

“My advice is always to treat supplements like drugs, meaning don’t take a pill unless you need a pill,” Moyad says. He urges restraint with melatonin not because there’s evidence it’s dangerous, but because of the lack of evidence showing it’s safe in high doses over long periods. Especially for parents who are giving melatonin to healthy children, Moyad says caution is warranted. Melatonin appears to be safe, and it could provide a range of health benefits. But there are a lot of unknowns.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com