On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, Lauren Hetrick was a 16-year-old sophomore at Hershey High School in Hershey, Pa. Her French class was just about to start when a strange announcement came over the P.A. system: “Attention, teachers: The computer tech is in the building.”

The teacher, hearing those words, logged onto her computer. Then she started to cry. She turned on the TV, and there was the North Tower at the World Trade Center, in flames. The class watched as a second plane hit the South Tower. Then the students watched the collapse of the tallest buildings in New York City.

Nearly two decades later, Hetrick has cause to see her teacher’s behavior that morning through a slightly different lens: She became a high school teacher herself, so helping students understand the events of 9/11 is part of her job too. This generation of students were almost all born after that defining 21st century moment, so while the attack may seem like yesterday to those old enough to remember it, to Hetrick’s students, it’s history.

Many teachers who remember what it was like to have been in school at that time use the memory to help their students connect to the topic. Hetrick, who chairs her school’s Social Studies department in Newville, Pa., shows her students the same Today show episode she watched that day. She also encourages them to listen to the stories of victims’ families and first responders recorded by StoryCorps, in hopes the personal recollections will make students more engaged “by seeing I’m truly invested in what we’re doing, seeing how much I’m caring about this, how emotional I get.”

When she first started teaching U.S. History in 2008, that lesson felt like déjà vu.

“I was teaching sophomores about my experience as a sophomore, and I would go home after that lesson and just break down,” she recalls. “I was having a hard time detaching. [Teachers] want to form a connection, but we also need to stay professional as historians and have that little bit of detachment. It’s definitely not easy to do.”

What Must Be Learned

It’s not surprising that teaching 9/11 as history is a delicate task. In addition to the emotional burden that falls on teachers who remember that day, the subject matter is sensitive and the images and documents that might be used as primary sources are disturbing. The story is also very much still being written, as the effects of 9/11 on American society continue to evolve.

There is also no national guideline that states are required to follow in terms of teaching the topic, so lessons will vary depending on the teacher or school district. In New York, for example, schools will observe a moment of silence on Wednesday, after Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed a law on Monday requiring observation of the anniversary. A 2017 analysis of state high-school social-studies academic standards in the 50 states and the District of Columbia noted that 26 specifically mentioned the 9/11 attacks, nine mentioned terrorism or the war on terror, and 16 didn’t mention 9/11 or terrorism-related examples at all.

That variation is part of the reason why Jeremy Stoddard, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Education, set out to analyze how teachers are talking about 9/11 in classrooms nationwide.

A new study released this month, on which Stoddard is the lead author, polled 1,047 U.S. middle- and high-school teachers and revealed that the most popular method of teaching about 9/11 and the War on Terror was showing a documentary or “similar video.” The next most cited method was discussing related current events. The third most mentioned approach was sharing personal stories, the way Hetrick does; Stoddard says younger teachers in particular tend to aim to get kids “to feel like they felt that day, to understand the shock and horror people felt that day.”

The survey built on his prior research looking at textbooks and classroom resources developed to teach about the event in the first few years after 2001. He and UW-Madison colleague Diana Hess studied nine of the bestselling high school U.S History, World History, Government and Law textbooks published in 2004 and 2006, and then did side-by-side comparisons between three of them and editions published in 2009 and 2010, noting how descriptions of the attacks evolved.

For example, four of the nine earlier textbooks mentioned the war in Iraq as part of the aftermath of 9/11, but when Stoddard and Hess were doing research in 2005, only one, McDougal Littell’s The Americans (2005), got into how evidence for the weapons of mass destruction claims had not yet been found. One 2005 textbook, Prentice Hall’s Magruder’s American Government, said that when Congress authorized President George W. Bush to take whatever measures were “necessary and appropriate” to neutralize the threat of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in the wake of 9/11, “it was widely believed that the regime had amassed huge stores of chemical and biological weapons”; the 2010 edition deleted the sentence about weapons of mass destruction. In some textbooks, the descriptions of the attacks got shorter as time went on. For example, that 2005 edition of The Americans said about 3,000 people were killed in the attacks, and then specified how many were passengers on the planes, people who worked at or were visiting the World Trade Center, and how many were first responders. The 2010 version cut out the breakdown of the casualties.

“A lot of the main themes that we saw way back in 2003 — in terms of, it’s a day of remembrance, a focus on the first responders and the heroes of the day and the actions they took, the world coming together in response to this horrible terrorist attack — a lot of those themes are still very much the way it’s being taught,” says Stoddard. “Middle schools are focusing a little bit more on first responders and heroes of the day. High school is where you would probably see more of an emphasis on the causes, the events leading up to it and maybe more on the response. High–school teachers did talk more about the Patriot Act and surveillance and some of those national-security-versus-civil-liberties types of issues.”

Read more: The TIME for Kids Guide to Talking About Tough Topics

Beyond the Textbooks

But, in keeping with some larger pedagogical trends in recent years, textbooks are not the go-to resource for learning about 9/11 in 2019.

Part of the reason is that, even if publishers update textbooks, schools may not have the budget to buy the latest edition; Kayla Turner, a high school social studies teacher in Raleigh, N.C., says some of the textbooks used in her classes haven’t been updated since 2001. Like Hetrick, Turner relies on personal experience to connect her students to the material. “I get teary-eyed with my students,” she says, especially when she explains that her father was a corrections officer who got called in to do crowd control at Ground Zero, and her cousin’s husband was a first responder.

So, in Stoddard’s new survey of secondary-school teachers, 71% said they use websites, 33% said they use specific curricula produced by non-profit and educational organizations and 23% said they use textbooks to explain 9/11 — and about 20% of participants said they didn’t have the curriculum or materials they needed to discuss 9/11 and the War on Terror.

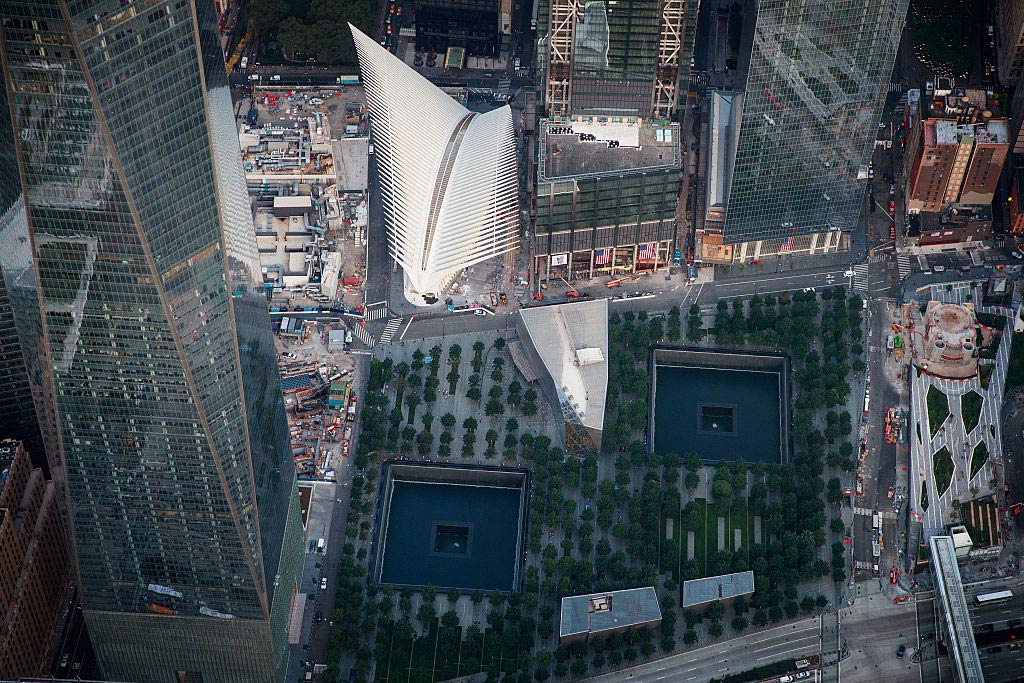

Some non-profits and educational organizations offer free online resources that help fill that void, especially for the youngest students. Teachers to whom TIME spoke mentioned the 9/11 Memorial Museum’s interactive timeline; the museum also offers a range of educational resources, all the way down to kindergarten-appropriate lesson plans that talk about the search-and-rescue dogs and emergency preparedness. Other resources include sites like Teaching Tolerance, which produces online guidelines for educators on debunking negative stereotypes about Muslims.

But flexible curricula can also introduce a different kind of obstacle for teachers. For example, Turner says she’s gotten pushback from parents for making a point to tell her students that the Islamist extremists who hijacked the planes on 9/11 don’t represent the views of all Muslims, and she’s had students who have come to the subject believing conspiracy theories that 9/11 didn’t really happen or was orchestrated by the government. Stoddard says her experience is not uncommon, as other teachers have told him they are increasingly having to field questions from students about conspiracy theories.

One aspect of the curriculum that has drawn particular debate is the question of whether pictures from 9/11 are too disturbing to use in classrooms. But, while textbook publishers and writers consider the appropriateness of showing them, teachers say photo and video are making 9/11 resonate with students — particularly because, as difficult as it may be for older Americans to imagine, students may not feel any particular sense of pathos or fascination about the day.

During a recent Twitter chat for social studies teachers on discussing 9/11, some teachers said they rely on more visceral images and records, but that they also remind students that the current government agencies such as the Department of Homeland Security and thorough airport security check-in processes are products of 9/11. Others point out ways students can help in a future crisis.

“You have an audience that’s easily bored,” says Don Ritchie, co-author of the 2018 edition of McGraw-Hill’s United States History & Geography. “When I talk to students, they complain they get bored with history. They want events with emotion and drama. Injecting some drama into the story is the best way to do that.”

‘A Long Time Ago’

But what do kids themselves say they’re learning about 9/11?

At the 9/11 Memorial on the weekend before this year’s anniversary, kids and parents alike told TIME that school wasn’t where they had learned most of what they knew about the attacks.

Liam Kerr Finger, a 10-year-old fifth grader visiting New York City with his family from Burlington, N.C., said he’d seen the news footage from 9/11 last year, in a documentary playing on TV at home. But his twin sister, Eleanor Ford Kerr Finger, hadn’t seen footage of the attacks before going to the museum, and was trying to get her head around the significance of the events. While she found it easier to draw a line between the causes and effects of other historical events she’d learned about — the Civil War and the end of slavery, the Revolutionary War and American independence — it wasn’t immediately clear how 9/11 had changed the world. One of her parents, Shellie Kerr, said she had been trying to explain to her kids that in fact they saw the effects of 9/11 in their everyday lives all the time, right down to the security line they had to wait on to enter the museum that day.

Joshua Petit-Day, 10, from Linden, N.J., said he had been learning about the attacks since first grade. His parents took him to the museum around the anniversary, and he said he learns more new details about 9/11 every September. To him, the events of that day are a reminder of how dangerous the world is. “Everyone should know what it means and why it happened because you never know if something like that is going to happen again,” he said.

“It’s not really talked about a lot,” said Che Rose, 14, a 10th grader from Jersey City, N.J., who said he got the feeling that teachers were reluctant to get into it. His sister, Jordana, 12, a seventh grader, had recently read a novel based on the attacks, Towers Falling. “At home we get more of the facts,” she said, pointing out that her father, who was with them, worked in midtown on 9/11. And, thinking about this moment that shaped the world into which she was born, she marveled at the fact that the attacks weren’t actually such faraway history after all.

“Feels like it was a long time ago,” she said. “Only 18 years ago? Feels further than that.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com