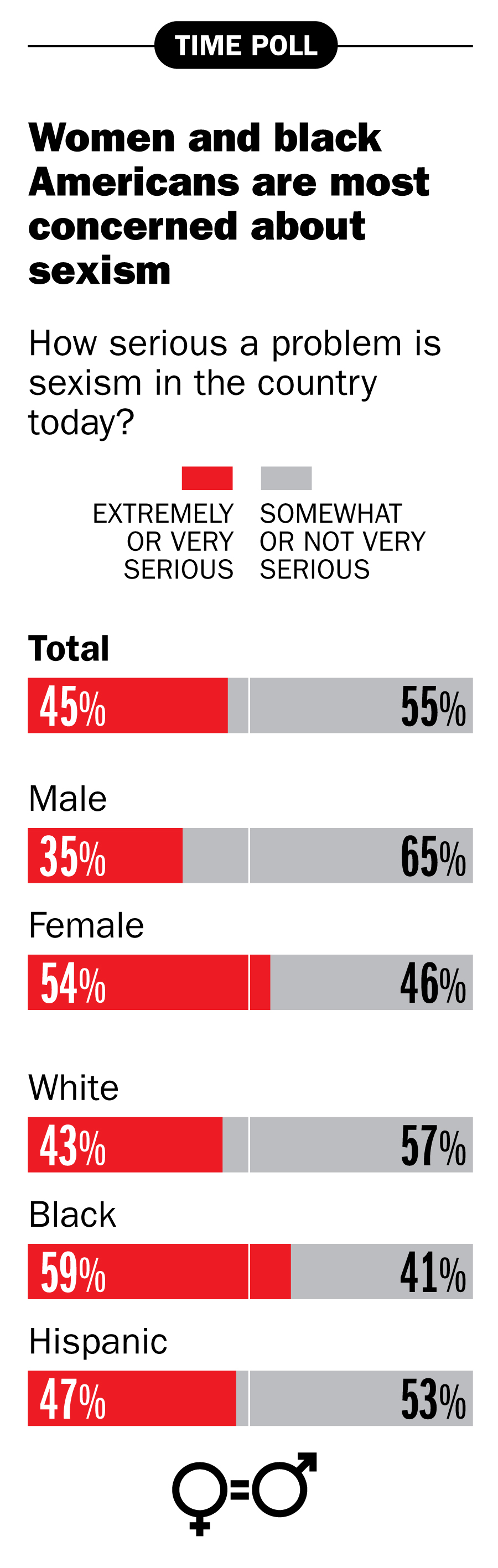

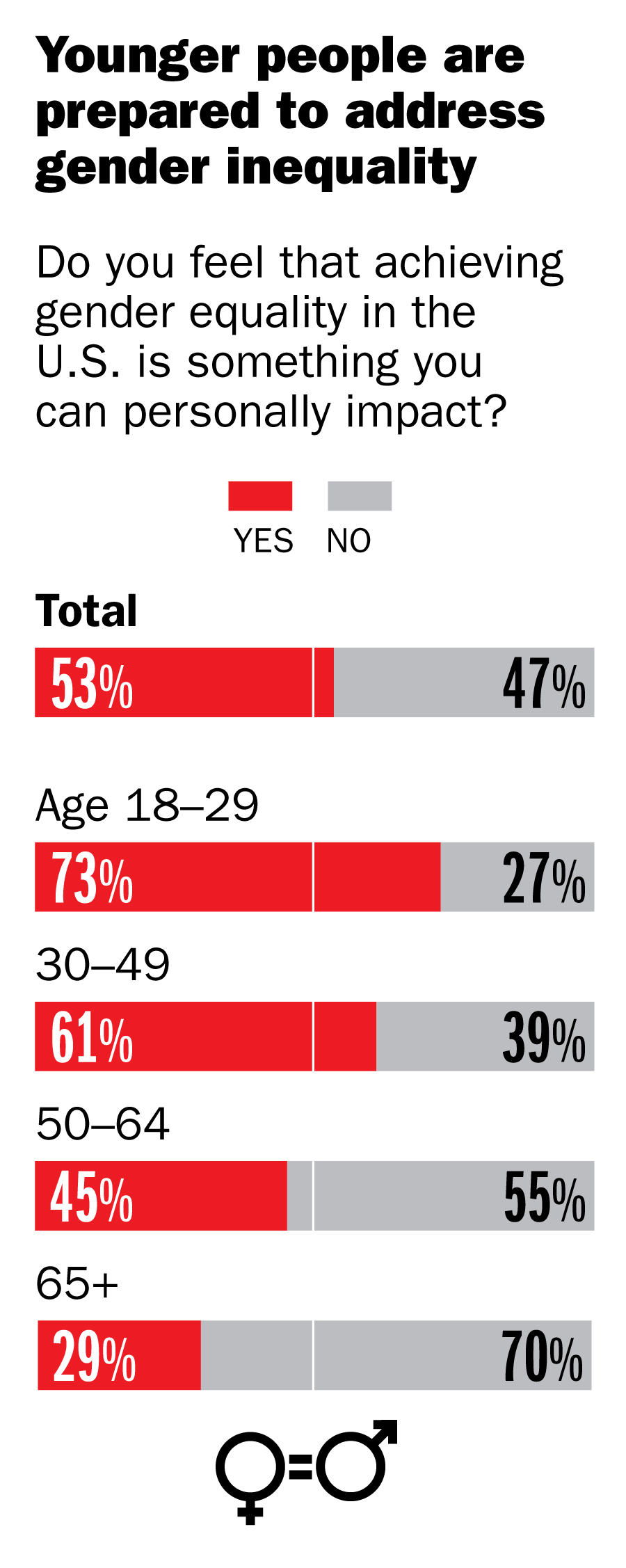

An overwhelming majority of Americans believe that gender inequality exists in the U.S. But there is stark disagreement about how pervasive the issue is and what should be done about it, according to a TIME-commissioned survey conducted by SSRS last month.

Respondents offered opinions on multiple aspects of gender inequality, including the wage gap, representation in government and unpaid work. The survey, conducted in partnership with Equality Can’t Wait, polled a nationally representative sample between August 19 and August 29, and found that men don’t consider the problems of gender inequality to be as severe as women do.

For example, 75% of people who took the survey believe that female workers are paid less than their male counterparts who do similar work. That may seem like a consensus, but only 62% of men held this belief, compared with 86% of women.

The disparity isn’t a surprise to survey respondents who have witnessed unequal pay first hand.

Take Erica Kaczmarowski, a 40-year-old accountant at a law firm in Buffalo, N.Y. Her job gives her insight into salaries at the law firm, where, she says, female paralegals earn less than male paralegals.

“I think most people don’t talk about what they make, especially at work,” Kaczmarowski says. “Some women may feel they might get fired or not get raises, depending on who their boss is. There’s a risk in bringing it up.”

Women working full time make 81% what their male counterparts make, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It could take another four decades to close the gender wage gap, according to projections from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, based on Census data. And it will take more than twice as long for women of color to reach parity.

Jessica Girard, a 32-year-old database developer with a master’s degree in computer and information systems, works at a mid-sized education firm in Tampa, Fla. She is the only black woman on her team of eight people.

When she asked her manager for a raise last year, he dismissed her, saying that they would eventually schedule a meeting to talk about it. That meeting never happened, despite her repeated requests.

After noticing that her colleagues got meetings to discuss salaries, Girard went to the company’s CTO, who said that her request had never been formally submitted. The CTO quickly approved the higher salary.

“I had a very legitimate case for getting a raise,” says Girard. She concedes that racial and gender discrimination is hard to prove, “but it was oddly coincidental that I was the one not getting heard.”

The TIME poll found a similar pattern for labor outside the workplace. Overall, 82% of respondents think that women spend more time than men performing unpaid tasks, such as managing a household and caring for children. But based on the poll, men generally underestimate the extent of that inequality.

U.S. women spend 67% more time doing unpaid work than U.S. men, according to the OECD, an intergovernmental economic organization. The majority of male poll respondents say that women do 20% or 40% more unpaid work. The majority of female respondents say 60% or 80% more, which is closer to the OECD figure.

Pamela Johnson, 52, has years of experience juggling career and caretaking. When her son was born 12 years ago, she was working full time in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. She recalls waking up at 3:30 a.m. to make bottles and do laundry before leaving for work at 5:30 while her husband, a law enforcement officer, was asleep. After putting in a full day, she cooked dinner and did the dishes. When her older relatives got sick, Johnson chipped in to help her mother care for them. “Women step up,” she says. “They sleep less.”

For the last two years, Johnson has commuted to Houston from Fort Lauderdale, where she works at the Department of Veterans Affairs. Due to her regular travel away from home, her husband has assumed many of the household responsibilities. “Now he sees all the housework is hard,” she says.

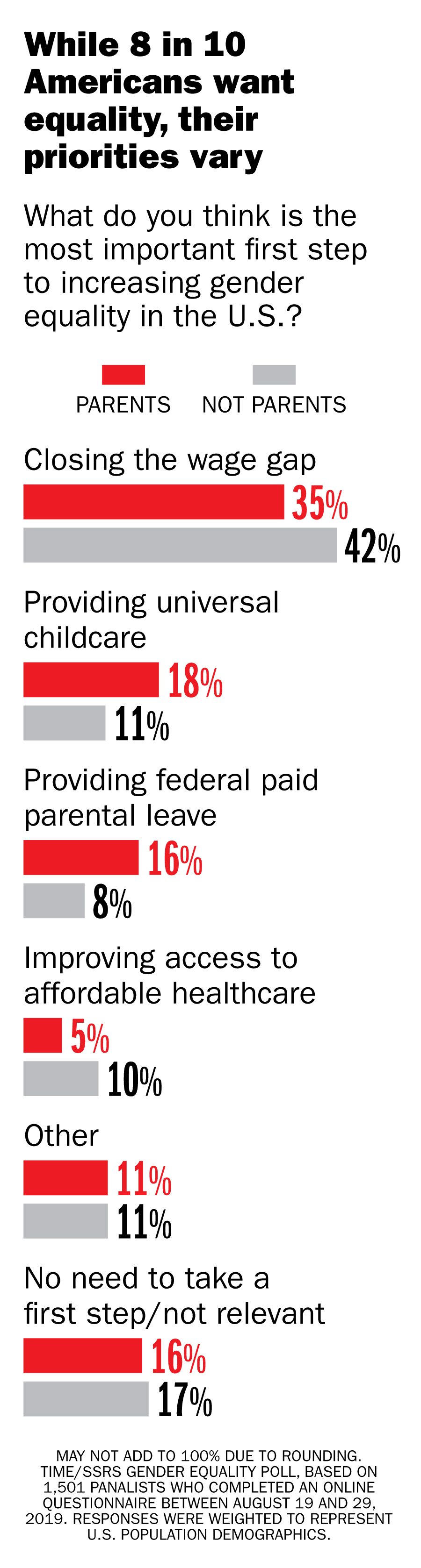

There is no silver bullet to achieve gender equality in the U.S. According to the TIME survey, 40% say closing the wage gap is the most important first step. But among parents, more than 1 in 3 say that parental support systems, such as universal childcare and federal paid parental leave, are more critical.

The average cost of child care in the U.S. is $9,000 per year, according to a 2018 report from Child Care Aware of America. But this is highly variable, as care for infants tends to cost much more than for older children, and certain states are more expensive. For example, in Massachusetts, the annual cost of an infant in a child care center is $20,400—or 17% of the median income for a married-couple family. The cost becomes even more prohibitive with multiple children.

The federal government’s current initiatives are insufficient for many American families. For instance, the Head Start programs are intended to serve children under age five who live below the poverty level. But among those eligible children, the programs serve 42% of pre-school children and only 4% of babies and toddlers, according to the Child Care Aware report. The federal government did, however, double the child care tax credit in 2017, from $1,000 to $2,000 per child.

Ryan Swadley, 35, from Green Bay, Wisc., recalls the challenges he and his wife faced when his kids, now ages 8 and 9, were born. The family was lower-income, receiving government assistance from the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program. They relied on family to help out. And his wife, who was studying for her master’s degree, took a job at a daycare in order to get a discount for the kids.

“It was a nightmare,” says Swadley. “If we had universal childcare, it would be so much easier for parents to work, and that’s something that hits mothers the hardest.”

Swadley recognizes that some large firms have recently started to offer longer paid leave for mothers and fathers. It’s a step in the right direction, he says, but notes that real change needs to be broader, through a state or federal initiative.

“It has to be more than just a hodgepodge of companies doing the right thing,” he says. “A lot of people in lower income, like we were, are not at those companies, so people who need it most are less likely to get it.”

Looking forward, about half of all respondents believe that gender equality will be reached within the next 50 years. But blacks are more skeptical: only 37% anticipate equality that soon, while 23% say it will take longer and 29% predict it will never happen.

While a majority of men see some level of inequality between the genders, a full quarter of surveyed men say that the country doesn’t need to take any steps to fight gender inequality. This may explain why progress is so slow: It’s hard to address a problem when so many don’t believe it exists.

This poll was conducted in partnership with Equality Can’t Wait – a campaign to accelerate gender equality in the U.S. led by Pivotal Ventures, an investment and incubation company created by Melinda Gates.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com