Little more than two hundred years ago, the Venezuelan liberator Simón Bolívar, languishing in Jamaica before resurrecting a revolution that would oust Spain from the Americas, wrote in a fit of near-suicidal fury, “I fear that democracies, far from rescuing us, will be our ruin.” Twenty years later, General Antonio López de Santa Anna abolished the newly minted Mexican constitution in a white-hot rage and declared, “I fought for liberty with all my heart, but even one hundred years from now, the Mexican people will not be ready for liberty. Despotism is the only viable government here.”

Today, a surprising number of Latin Americans would agree. According to the multinational polling service Latinobarómetro, less than half of all Latin Americans today favor democracy, and less than a quarter are satisfied with what it has achieved in their countries. But given the region’s history, it’s perhaps not so surprising that so many of its people have soured on the idea. After all, democracy there has faced obstacles from the start.

In the 19th century, Latin America emerged from its wars of independence ravaged, and, although its revolutionary armies had been largely people of color, those underclasses went ignored. The principles of Enlightenment that had fueled the revolutions were cast aside as rich Creoles (whites of Spanish ancestry) scrambled to appropriate the wealth the colonial overlords left behind. Governments were improvised in a way that kept the darker races in servitude and granted whites the seats of power. The rule of law—indispensable to a free people—was abandoned as one dictator after another rewrote laws according to his caprices. Indians and blacks, having fought furiously for liberty, were cast back into servitude. Bigotry, institutionalized by Spaniards, hardened under their descendants, and a virulent racism became the region’s tinderbox. A nervous era followed.

From 1824 to 1844, in its first 20 years as a liberated republic, Peru—the anxious heart of a gutted empire—counted 20 presidents. Bolivia saw three in the course of two days. Argentina had more than a dozen leaders in its first decade. A century later, in 1910, bucking the brutal bias that persisted between white and brown, Mexico undertook yet another revolution, and then the Latin American masses turned a collective eye toward insurrections in general.

The only stability for the next century seemed to be in despots. When Fidel Castro’s revolution inspired Latin America’s underclass to rebel, a robust, transnational network of military generals swatted it down with a fierce counterinsurgency force backed by the United States, Operation Condor. In Argentina, General Jorge Rafael Videla swanned through Buenos Aires’ 1978 World Cup celebrations even as malcontents were being flayed alive, or herded into concentration camps, or drugged and dropped from biplanes and helicopters into the muddy Paraná.

By the late 1970s, 17 out of 20 Latin American nations were ruled by dictators. Twenty years later—in a remarkable volte face—18 had replaced the iron fist with functioning democracies. Like a row of tumbling dominos, military juntas succumbed to democratic governments. Ironically enough, Castro’s successful communist revolution in Cuba, the very excuse for the application of an iron fist in many countries, had inspired a growing hunger for equality in the masses. A new sense of possibility among liberal politicians began to take root.

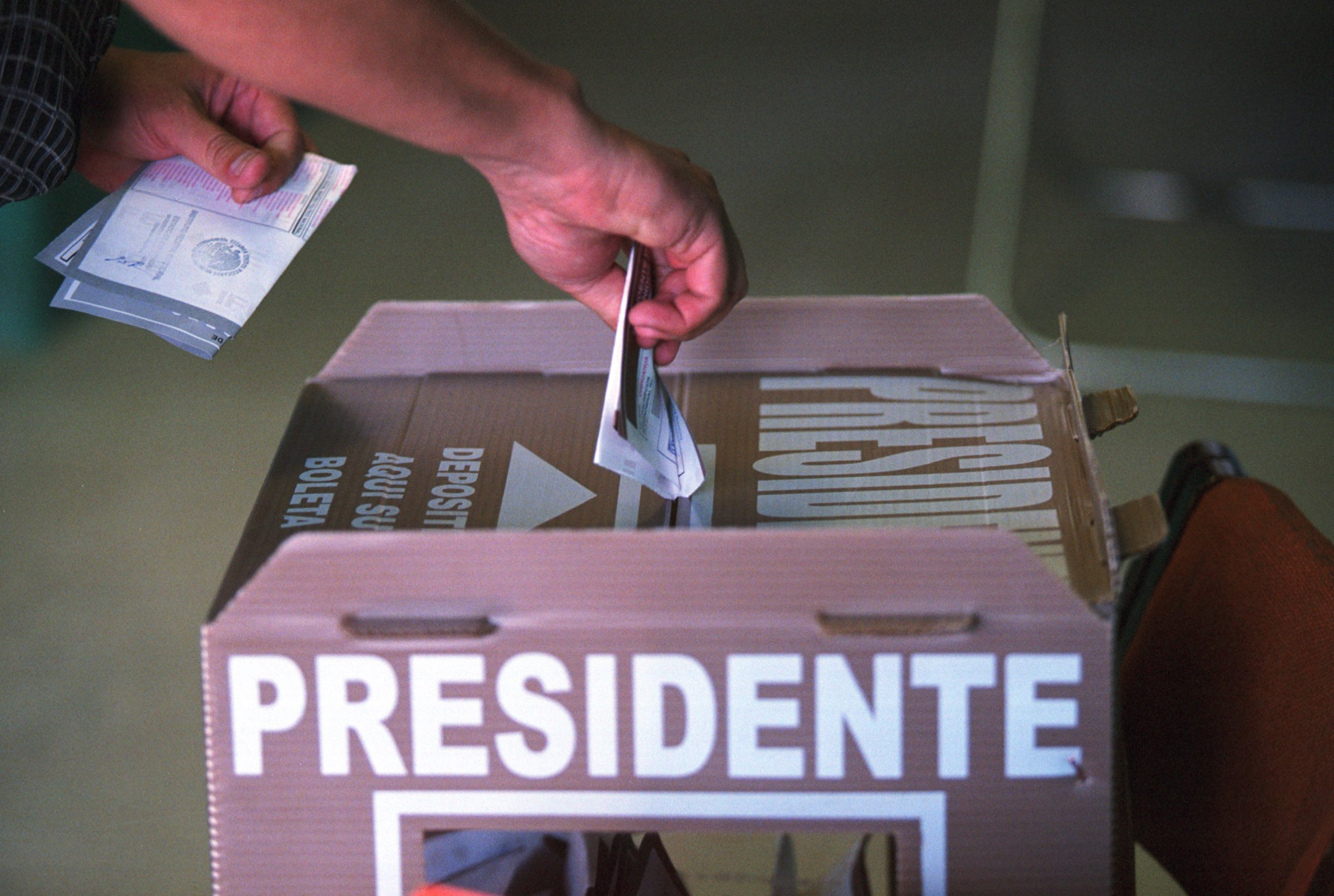

By the end of the 1980s, democratic elections had rocked Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Nicaragua, Paraguay and Peru. Eventually, Panama, El Salvador and Guatemala would follow. By 1999, only two nations had resisted democracy’s lure: one was Castro’s Cuba; the other was Mexico, which had been in the grip of a single party for much of the 20th century. A year later, in 2000, with the overthrow of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, Mexico became one of Latin America’s most exemplary democracies, sending its citizens to voting booths every six years in orderly elections.

At first, the democratic idea seemed to work for Latin America, bringing unprecedented economic growth, the modest rise of a middle class and a dip in the rampant inequality that has plagued it since Columbus ran out of gold and decided to start a slave trade instead.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

All that was before Latin American democracy itself changed, morphing into a version only a magical realist might imagine. These democratically elected presidents expanded the military’s role, suspended constitutions, dodged prosecution, blocked checks on their power, perpetuated their rules and became, as Gabriel García Márquez put it, “the only mythic creature Latin America has ever produced.”

Evo Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, a poor coca leaf farmer who gave Bolivia hope and a measure of equality, became what so many of his cohort have become: rich and rabidly authoritarian—a classic, hidebound caudillo. Though they did varying levels of damage, a spate of Latin American leaders turned toward one form or another of corruption, violence or suppression of opponents. There was Chile’s Augusto Pinochet, Peru’s Alberto Fujimori, Argentina’s Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Ecuador’s Rafael Correa, Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega. Hugo Chavez claimed to strengthen the rule of law even as he placed Venezuelan courts under government control. Nicolás Maduro has continued that brazen authoritarianism; his government has been linked to the shutting down of investigations into bribes by Brazilian corporate giant Odebrecht. A 2018 report by the World Economic Forum listed Venezuela, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Bolivia and Honduras—all titular “democracies”—as among the countries least governed by the rule of law. In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro was brought to power by an anticrime, anticorruption coalition intent on correcting this trend. But for all the tough talk and pretty promises, six months later, unemployment has increased, the economy is in downward spiral, his son has been accused of corruption (which he denies), and the violence has grown only worse.

The reason for this failure of democracy goes beyond the political.

Just as silver brought wealth to the Spanish elite but unspeakable cruelty to native Americans, an extractive society and an unrestrained illegal drug trade have brought riches to a very few and conflagration to the overwhelming many. Here is an endlessly recurring history, nudged along by the region’s gravest affliction: its dire inequality. Latin America continues to be the most unequal region on earth precisely because it has never ceased to be colonized—by exploiters, conquerors, proselytizers, mafias—and, for the past two centuries, by its own tiny elite.

The sense throughout Latin America is that this needs to be fixed. How can the top oil-rich country on the planet, Venezuela, be patently unable to feed itself? How can the highly educated populations of Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay suddenly all find themselves fumbling in the dark, their electrical grids simultaneously in blackout? How can booming economies like Colombia’s or Mexico’s thrive even as drug wars tear through their populations and leave about half a million dead?

If body counts are any measure, Latin America is the most murderous place on earth. The ten most dangerous cities in the world are all in Latin American countries. This is perhaps what threatens Latin America’s democracy most. Too often, the violence is premeditated, cold-blooded, carried out by government officials and criminal cartels alike. Little wonder that the United States has seen a flood of desperate immigrants streaming across its border. Fear is the engine that drives Latin Americans north.

Little wonder, too, that the majority of Latin Americans see their democracies as foundering. Economies may thrive. Foreign investment may prosper. But the people don’t believe they are substantially better off. They long for a firmer hand. Perhaps these are symptoms of the growing global suspicion that democracy is rigged against the ordinary citizen, that it has less to offer than an authoritarian government with a buoyant free market.

In the end, Latin America’s wild race to democracy has failed to overcome the region’s difficult history. The wounds left unattended—inequality, injustice, corruption, violence—are powerful catalysts for discontent.

Marie Arana, a native of Peru, is the author of the book Silver, Sword, and Stone: Three Crucibles in the Latin American Story, available now from Simon & Schuster.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com