Published in partnership with The Fuller Project, a non-profit newsroom that reports on issues impacting women.

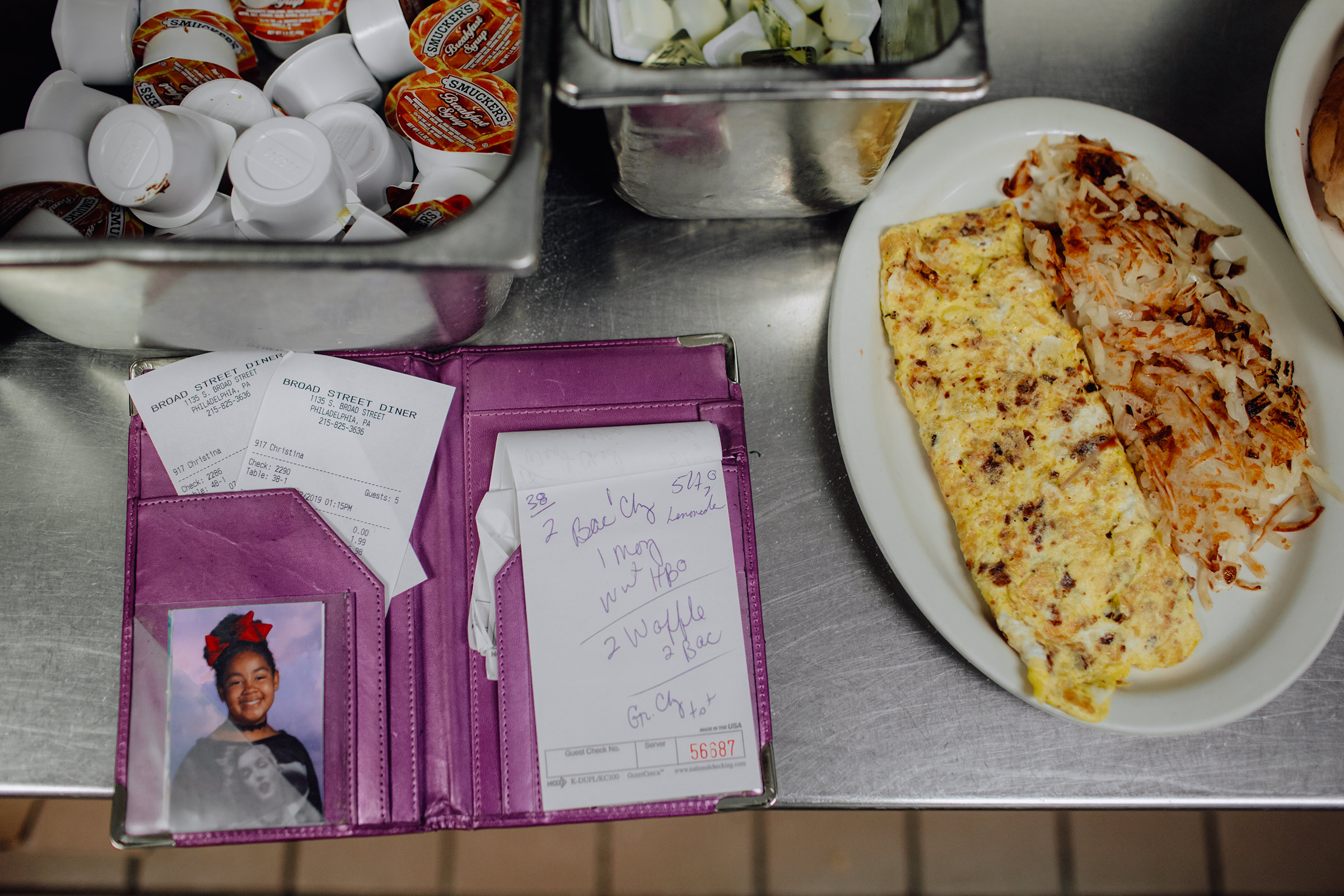

After an eight-hour shift on her feet, shuffling between a stuffy kitchen and the red vinyl booths of Broad Street Diner, Christina Munce is at a standstill in traffic. Still wearing the red polo shirt and black pants required for work at the diner in South Philadelphia, she’s arguing with her colleague Donna Klum. They carpool most days to spare Klum a two-hour commute on public transportation that involves three transfers.

“It’s not O.K. for people not to tip,” Munce says from the driver’s seat, the Philly skyline passing by. Klum believes that bad karma will catch up with non-tippers, but Munce, a single mother who relies on tips to live, doesn’t care much about their fate. “I have to make sure that my daughter has a roof over her head,” she says. The desire for cash over karma is understandable: Munce’s base pay is $2.83 an hour.

The decade-long economic expansion has been a boon to those at the top of the economic ladder. But it left millions of workers behind, particularly the 4.4 million workers who rely on tips to earn a living, fully two-thirds of them women. Even as wages have crept up–if slowly–in other sectors of the economy, the minimum wage for waitresses and other tipped workers hasn’t budged since 1991. Indeed, there is an entirely separate federal minimum wage for those who live on tips. It varies by state from as low as $2.13 (the federal tipped minimum wage) in 17 states including Texas, Nebraska and Virginia, up to $9.35 in Hawaii. In 36 states, the tipped minimum wage is under $5 an hour. Legally, employers are supposed to make up the difference when tips don’t get servers to the minimum wage, but some restaurants don’t track this closely and the law is rarely enforced.

Waitresses are emblematic of the type of job expected to grow most in the American economy in the next decade--low-wage service work with no guaranteed hours or income. Though high-paying service jobs have been growing quickly in recent months, middle-wage jobs are growing more slowly and could decline sharply in the event of a recession, says Mark Zandi, chief economist with Moody’s Analytics. Those who lose their jobs in a recession usually move down, not up, the pay scale. Jobs like personal-care aide (median annual wage $24,020), food-prep worker ($21,250) and waitstaff ($21,780) are among the fastest-growing occupations in America, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). They have much in common with the burgeoning gig economy, in which people turn to apps in the hope of getting shifts delivering food, driving passengers and cleaning houses.

This “sometimes” work has put the stress of earning a weekly wage, paying for health insurance and saving for retirement squarely on the shoulders of workers. Munce is on food stamps and Medicaid, and many days doesn’t make it to the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. One of her recent paychecks read $58.67 for 49 hours worked. Add in the $245 she took home in tips, and she made about $6.20 an hour. She wants to work 40-hour weeks, but some days the diner is slow and she gets sent home early. “I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, all I do is save money,” Munce says.

But these employers are hiring, and these jobs are becoming a fallback for people whose former jobs placed them solidly in the middle class. Food-service jobs have grown nearly 50% over the past two decades, to 12.2 million, according to the BLS. They are on track to surpass America’s manufacturing workforce, which, at 12.8 million, has fallen 25% over the same period.

Markets have swung wildly in recent weeks on fears of a possible recession, which could speed up the nation’s continuing shift from one that makes things to one that serves things. The last recession, from 2007 to 2009, took a sharp toll on industries that make things in America, with construction and manufacturing each losing 1.9 million jobs in the five years after the recession began. In contrast, industries like health care and food service added hundreds of thousands of jobs in the same period.

If another recession starts, “the primary hit is going to generally be in sectors that don’t involve providing basic services to other people,” says Jacob Vigdor, an economist at the University of Washington. On Aug. 20, President Trump, while declaring the economy still strong, said the Administration is examining various options to bolster the economy. Still, whenever the next recession comes, more workers will have to turn to the booming service industry, where low wages and unstable hours are the norm.

Christina Munce didn’t plan to be a waitress. She was in school studying massage therapy when, at 21, she got pregnant, and started waiting tables to put away the cash she would need as a young mother. She doesn’t regret a thing–her daughter, now 11, is her whole world, her name tattooed in cursive on Munce’s forearm. Pictures of the two posing together dominate the otherwise blank walls of their government-subsidized two-bedroom apartment. But being a single parent has limited Munce’s job options, since she needs the flexibility to take care of her daughter.

Tipped workers have always been an underclass in America. The concept was popularized in 1865, when some formerly enslaved people found employment as waiters, barbers and porters; still seen as a servant class, they were hired to serve. Many employers refused to pay them, instead suggesting that patrons tip for their service. A 1966 law tried to bring some measure of security to these jobs, requiring employers to pay a small base wage that would bring tipped workers up to the federal minimum wage when combined with their tips. In 1991, the tipped minimum wage was equal to 50% of the value of the overall minimum wage, but it’s stayed at $2.13 since then, as the minimum wage has nearly doubled. In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed legislation that froze the wage for tipped workers at that amount. It hasn’t changed since.

The regular minimum wage has doubled in that time. If the tipped minimum wage had even risen with inflation since 1991, it would be $6 an hour, according to research from Sylvia Allegretto, co-chair of the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics at the University of California, Berkeley. Only 12 states currently pay waitstaff above that.

The serving workforce remains a microcosm of pay disparities in the broader economy. According to 2011–2013 data from the Economic Policy Institute, people of color make up nearly 40% of the workforce that falls under federal tipped-minimum-wage rules, which includes nail-salon workers and car-wash attendants. The flexibility of restaurant work is in part why more than a million single mothers are on the job. After eight years working at the 24-hour diner, Munce, 32, mostly gets the shifts that she wants–working breakfast and lunch and leaving by 3 p.m. when her daughter gets out of school–so for that, she’s grateful. When her daughter got bullied at school and Munce had to pick her up, Munce was able to get other waitresses to cover for her without getting in trouble for calling off work–though of course this also meant she didn’t get paid. When her daughter was younger and Munce couldn’t find anyone to watch her, she’d bring her daughter to the diner and have her sit quietly in a booth with crayons.

Half a century ago, people like Munce without a college education could expect to make a middle-class wage. But in recent years, as male-dominated manufacturing jobs have been outsourced or automated, women are contributing more to their families’ paychecks, and more of the 40% of Americans with no more than a high school education are being pushed into the service sector–as waitresses, domestic workers, hairdressers and Uber drivers.

Consumer spending on restaurants surpassed spending in grocery stores for the first time in 2015, and to support that, the BLS projects more than 500,000 food-serving job vacancies between 2016 and 2026, a higher number of openings than in all but three occupations it tracks.

“We’re not a sliver of the economy,” says Saru Jayaraman, co-founder of the Restaurant Opportunities Center, an advocacy organization pushing to eliminate the tipped minimum wage. “We’re increasingly the jobs that are available to every new entrant into the economy, including people being laid off from other sectors.”

Karen Baker, 52, one of Munce’s managers at Broad Street Diner, says she once made $90,000 a year as an assistant production manager in a plant that made plastic soda bottles. When the plant moved to Iowa, she didn’t want to uproot her family so she returned to the service industry. “That’s one good thing–if you can’t find a job anywhere else, you can always find a job waitressing,” she says.

This is true of many service jobs, says David Autor, an economist at MIT who studies the future of work. But as job seekers are flooding into those fields, they’re being met with low pay, few benefits and no raises as they age and gain more expertise. In 1980, 43% of workers without a college education were in middle-skill jobs; by 2016, that number had dropped to 29%, Autor says.

A raise for tipped workers, then, could mean a raise for middle-class families across the country, says Heidi Shierholz, an economist at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute who worked in the Department of Labor under President Obama. In the seven states where servers are paid the regular minimum wage for those states before tips, including Minnesota and Oregon, the poverty rate for waitstaff and bartenders is 11.1%, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Where there’s a separate tipped wage, the poverty rate among waitstaff is 18.5%.

Under Pennsylvania’s $2.83-an-hour tipped minimum wage, Baker’s colleague Debbie Aladean, 74, says she can’t retire because she has so little Social Security. Olivia Austin, a 30-year-old waitress in rural Pennsylvania, started driving across the border to a restaurant in New York, where there was a higher minimum wage, because she couldn’t save any money as a waitress in Pennsylvania. “Most of the people I worked with could barely pay their rent,” she says.

Of course, some do quite well in the restaurant industry–especially white men, who are more frequently employed by fine-dining establishments. According to the National Restaurant Association (NRA), a lobbying group that represents more than 500,000 restaurant businesses, the median hourly earnings of servers, including tips, actually ranges from $19 to $25 an hour. Asking owners to do away with tipping and pay workers a $15-an-hour set wage puts too much burden on business owners and could sink one of the economy’s strongest-growing sectors, they say.

“We need a commonsense approach to the minimum wage that reflects the economic realities of each region, because $15 in New York is not $15 in Alabama,” says Sean Kennedy, the executive vice president of public affairs for the NRA.

The owner of Broad Street Diner, Michael Petrogiannis, is supportive of raising wages. “If [the minimum wage] goes to $15 an hour, then we’ll go to $15 an hour, no problem. I support that,” he says. He leaves reporting tips up to the waitstaff, and his employees have not complained about being shorted. “We want them to make whatever they have to make.”

The strength of the service sector offers a sort of tenuous job security for waitresses, but it comes with few protections. Sexual harassment is rampant. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission receives more complaints of sexual harassment from the restaurant industry–more than 10,000 from 1995 to 2016–than from any other industry. Many waitresses have come to expect it. On a shift in July, Munce chirped back at offhanded sexual comments as readily as she dished out nicknames to regulars. When a man called her “thick and delicious” on his way out the door, she replied, “I think you mean tiny and tasty,” without skipping a beat.

After 12 years of waitressing, Munce’s somewhat hardened to the disrespect, but for her, the fickleness of the work is a bigger problem when it affects her family’s well-being. Her daily income depends on whether people decide to brave the heat or snow to dine out the day she’s working. It depends on whether customers order the $5.29 breakfast special or the $16.99 New York sirloin strip with two eggs, and whether they leave 20% of their bill. It depends on how many other waitresses are working that day, all hungry for tables.

This lack of certainty is stressful for waitresses, but as more workers face this reality, it has implications for the broader American economy, which relies on consumer spending to drive growth. Munce has saved about $1,000 by putting aside every $5 bill she earns in tips, but she can’t seem to ever get ahead. During a recent shift, she was staring down a weekend where she’d need cash for a cake for her daughter’s 11th-birthday party, $650 for a new evaporator for her car and quarters for the laundry. She feels the weight of taking a day without tips, wondering whether she’ll have enough to pay for back-to-school season, or the money that finally allowed her to get an air conditioner for her apartment. “My mind is always calculating,” she says of each tip, good or bad. Though the women at the diner will chip in and pay for one another’s expenses in case of emergency–a car accident, a babysitter or even funeral costs–slow shifts mean they’ll have to lean more on the one free meal they get at work, or make another trip to the food bank, or dip into whatever cash they have stored away from a better week.

Because their pay is so unpredictable, the women at Broad Street Diner sometimes have to pull double or triple shifts when they’re short on cash. The day before Munce drove Klum home, Klum had worked her regular day shift, taken her 5-year-old daughter to a public splash park, and then gotten a call from her manager at 11 p.m. to come in for a night shift three hours later. Klum paid for a Lyft to the diner, since public transportation doesn’t run to her apartment after midnight, then worked a double shift, from 2 a.m. to 3 p.m. “The diner’s been slow, so I really needed it,” Klum says. But as bad as the money can be, it’s helpful to be able to go home with cash in hand. She still holds out for the chance of one big payday, obsessing over YouTube videos where women are left a $12,000 tip. But when Munce suggests that they would be better off getting a fair hourly wage rather than depending on tips, Klum balks. “I would never do this without tips,” she says.

Restaurant owners say that the problem isn’t low wages, or even low tips–it’s that the federal government should enforce its requirement that waitresses make at least the minimum wage after tips. But the sheer number of restaurants in America–an estimated 650,000 and growing–makes that difficult.

“We could have spent all of our time on tipped-minimum-wage enforcement because the violations are so pervasive,” says David Weil, who was the head of the Wage and Hour Division in the Department of Labor under President Obama. Weil’s division did 5,000 investigations into the restaurant sector in his time in the department, but “we were just scratching the surface,” he says.

The Trump Administration last year revoked an Obama-era rule that would have increased enforcement on restaurants that make tipped employees spend more than 20% of their time on non-tipped work.

The federal government does help low-wage workers like waitresses in other ways–with food stamps, subsidized housing and health care. Some cities have raised their own tipped minimum wages; others have opened wage-and-hour enforcement offices, but investigations on behalf of tipped workers often remain a low priority. In Philadelphia, a branch of the Mayor’s Office of Labor looks into complaints of wage theft. But the city’s messaging suggests it devotes more staff and resources to its long-standing offices guaranteeing fair pay for construction and government workers; its department that enforces wage-theft complaints was formed in 2015 and has only four employees. The chief of staff of the Mayor’s Office of Labor, Manny Citron, who is responsible for enforcement, says that although he was “not a pro on what our labor law says,” he believed that people who didn’t earn $7.25 an hour with tips “could just be a bad waiter,” and he falsely asserted that state law guarantees only $2.83 an hour. Without any documentation showing that cash tips didn’t bring waitresses to the minimum wage, he says, it’s hard for his office to take any action.

In July, the House passed the Raise the Wage Act, which would phase out the tipped minimum wage nationwide by 2027, eventually bringing all low-wage workers to $15 an hour. “Every member of this institution should be fighting to put more money in the pockets of workers in their communities,” Speaker Nancy Pelosi said on the House floor when the bill was passed. In 2019 alone, at least 12 states as politically varied as Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Indiana introduced legislation to end the tipped minimum wage.

But the Raise the Wage Act has little chance of advancing in the GOP-controlled Senate. It has vocal opponents in the NRA and the Restaurant Workers of America (RWA), a group of servers who want to keep tipping. “It’s a system that works,” says Joshua Chaisson, a Maine waiter who is a co-founder of the RWA.

Restaurant owners say they aren’t the ones who should pay the price of America’s shift to a service economy. “Today, the middle class has been gutted, but [lawmakers] are trying to legislate entry-level low-skilled jobs into living-wage jobs where you can raise a family in New York, one of the most expensive places in the world,” says Andrew Riggie, executive director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance, which represents hotels and restaurants. “We can’t address all societal ills on the shoulders of small-business owners.”

In the long, final days of summer, business at Broad Street Diner has been slow. Munce tries to stay positive. The customers and staff of Broad Street Diner are her family, more or less, and not just because her sister, Jeanne, is also a waitress there. Munce speaks fondly of one of her regulars, Bill, an elderly man who likes his toast dark as a hockey puck. “They’ve got the best girls in here, and I’ll tell ya, not one grouch,” Bill says to no audience in particular one day this summer.

For Munce, it all adds up: the freebies, the walkouts, the cops receiving a 50% discount, the mess-ups from the kitchen–each one a knock to her take-home pay. “I am a people person. But at the end of the day, your compliments and smiles are not enough,” she says during one of her shifts, a sheen of sweat on her forehead.

She hopes she can give her daughter a better life than she had growing up. Her dad served in Vietnam and her mom always scraped by on odd jobs, she says, but it’s harder to string together a living these days. She lives a couple of miles from where she grew up. Is she really doing better than they did? She tells her daughter that education is the most important thing, that she needs to get good grades, no matter what. “I say, ‘I just want you to be better than me,'” she says. Not that she’d steer her daughter away from waitressing, necessarily. If you’re a people person, Munce says, it can be fun to talk to strangers all day. Depending on them for tips, though, is something else.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Behind the Scenes of The White Lotus Season Three

- How Trump 2.0 Is Already Sowing Confusion

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: All Those Presidential Pardons Give Mercy a Bad Name

Contact us at letters@time.com