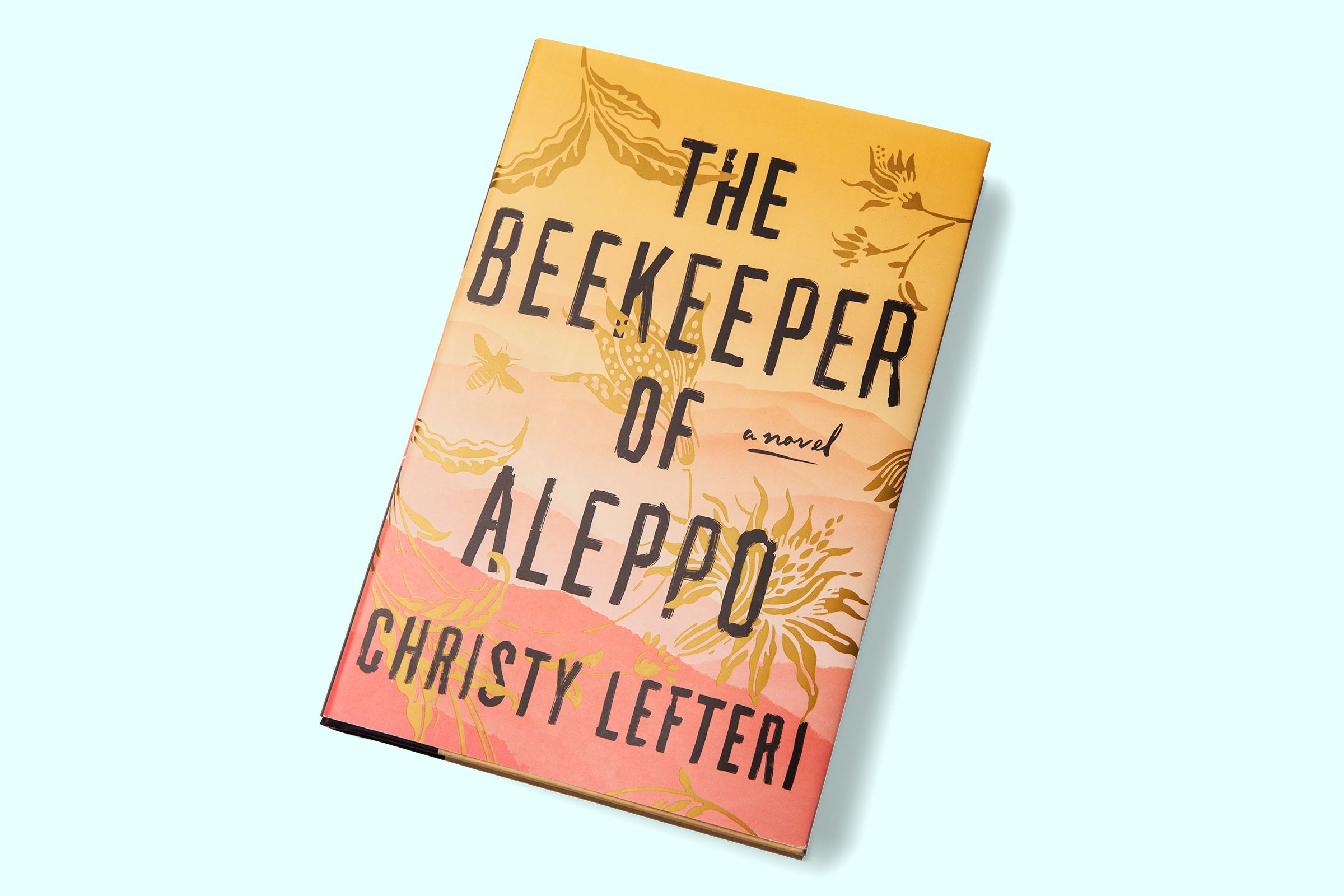

After two summers volunteering in a refugee center in Athens as thousands of families flooded into Greece, Christy Lefteri found herself wondering what it means to see, and be seen. From the question sprang her second novel, which follows Nuri, a Syrian beekeeper, and his wife Afra, an artist blinded by an explosion, on a journey to find safety in the U.K.

We tend to hear refugee stories in the abstract: millions of people fleeing war, poverty and persecution–words that carry no specifics. But in The Beekeeper of Aleppo, Lefteri gives us a deeply researched, intimate look at the lives of one couple. Narrated by Nuri, the novel weaves together two time lines: one starting in Aleppo in 2015 as the couple decides to leave Syria and make the dangerous journey through Turkey and Greece, and the other from a seaside town in England the following year, where they are applying for asylum.

Lefteri subtly critiques media portrayals of refugees, asking us to delve beyond the crisis imagery we see. In one scene at the port of Piraeus in Athens, there’s a flash of light as a black object is pointed at Nuri: “A gun? My breath caught in my throat, I struggled to inhale, my vision blurred, my neck and face felt hot, my fingers numb. A camera.” Nuri realizes it hadn’t occurred to the photographer that “he was taking a picture of a real human.”

A former psychotherapist and the daughter of Cypriot refugees, Lefteri sensitively charts what it’s like when war comes home, alert to the subtle effects of trauma and grief. Nuri and Afra are not broadly sketched as victims, but rather suffer in different and complex ways from PTSD–a condition still rarely explored in literature beyond the accounts of veteran fighters or war correspondents. Nuri and Afra manage to escape their shattered hometown, but they cannot escape the memories that haunt them. “You are lost in the darkness,” Afra tells Nuri, reminding us that even if she is the one who has lost her sight, he is even more cut off from his loved ones–and himself.

Lefteri’s slow-building narrative rarely veers into sentimentality or overwhelming bleakness. Nuri’s love of beekeeping and Afra’s gift for art, interspersed with happier recollections of Syria, offer a glimpse of the beauty still within their reach. By creating characters with such rich, complex inner lives, Lefteri shows that in order to stretch compassion to millions of people, it helps to begin with one.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Naina Bajekal at naina.bajekal@time.com