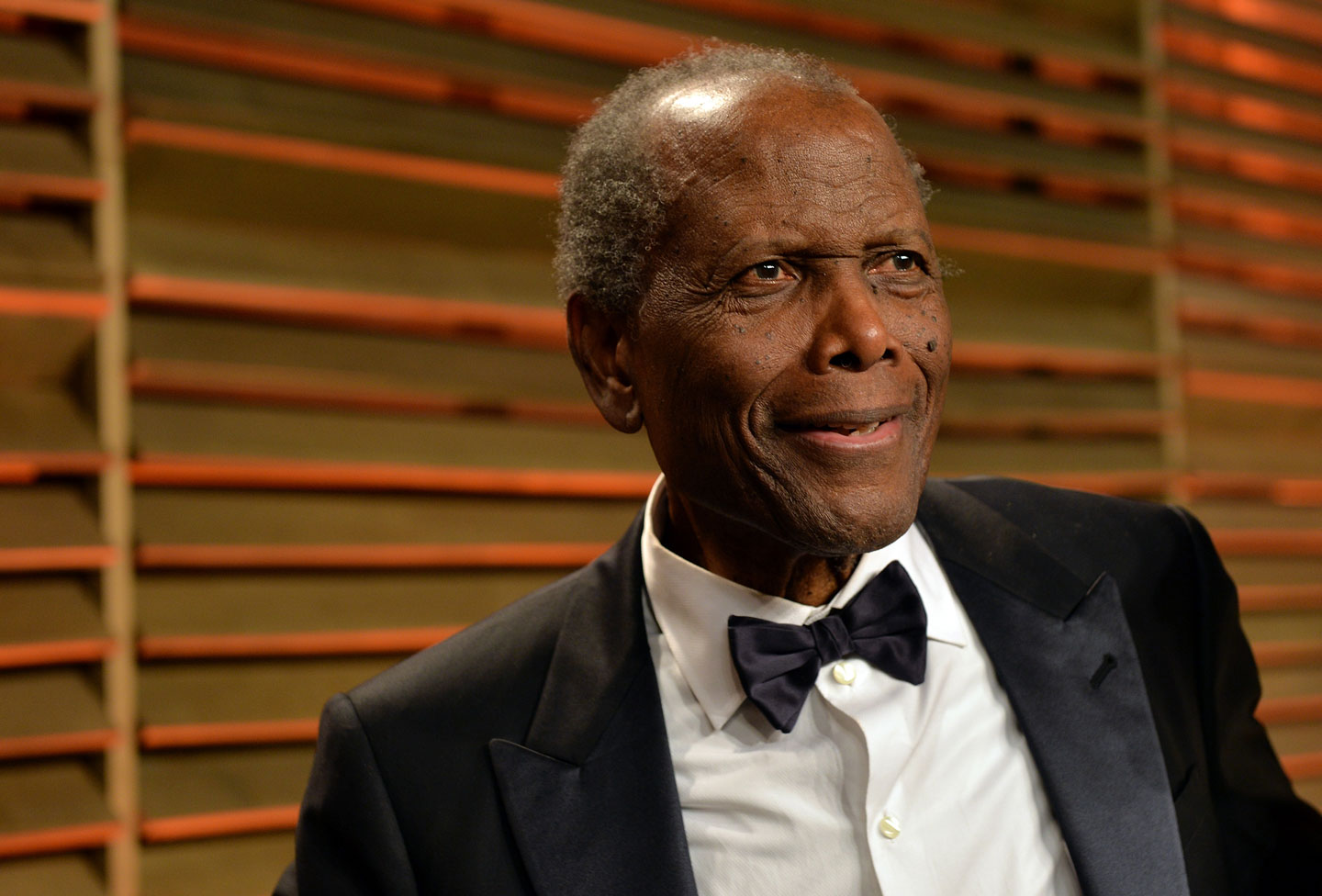

There were great actors before Sidney Poitier, and great ones since. But the world would have been markedly different without Poitier—the first Black actor to win an Oscar for Best Actor—who arrived on the theater and film scene in post-World War II America just as this country, not to mention the world, was scrambling to reassemble itself.

Poitier, who has died at 94, helped reshape that world to such a degree that we’ll never be able to reckon fully with his impact. All actors owe him a debt, and all Americans do, too.

Poitier was born in Miami in 1927, while his parents, tomato farmers, were visiting from their home of Cat Island, in the Bahamas. The youngest of seven children, Poitier grew up on Cat Island and in Nassau, before moving to Miami at age 15 to live with his older brother. From there, he made his way by bus to New York City, where, after a brief, unhappy stint in the Army, he attempted to launch a career onstage.

Finding his way

There were some early false starts: He auditioned for the American Negro Theatre by reading an article from True Confessions magazine, not realizing he was supposed to have brought a dramatic text. But before long he’d earned a spot in the road company of Anna Lucasta, Philip Yordan’s play about working-class Polish-American family, which had been adapted by the American Negro Theatre with an all-Black cast. In 1949, just after Poitier had landed a good role in the Theatre Guild of America’s production of Lost in the Stars, he auditioned, on a whim, for a Hollywood movie. He was as surprised as anyone when he landed the part: In Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s No Way Out, Poitier plays a young doctor at a county hospital, Luther Brooks, who stirs the anger of a racist thug, Ray (Richard Widmark), when Ray’s brother dies after being treated by Brooks.

No Way Out, with its backdrop of racial unrest and its awareness of complex striations of race and class, is a striking movie, and Poitier’s performance in it, especially for a film debut, is remarkable. When Widmark’s Ray sees Brooks approaching his brother, suffering from a gunshot wound incurred during a robbery, he sneers, “I don’t want him, I want a white doctor.” As Brooks registers those words, Poitier’s face is so composed you could mistake its quietude for passivity. But what he’s really showing is a mask of endurance, a reminder that every muscle in Brooks’ body is accustomed to fielding these types of insults, and not one has stopped him yet. The look in his eyes is partly defiant, but also perhaps incredulous—as if he still can’t believe that white humankind is still hung up on all of this.

A political awakening

Poitier continued to land significant roles through the 1950s, in films like Zoltan Korda’s Cry the Beloved Country (1951), Richard Brooks’ Blackboard Jungle (1955) and Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958). But the early years of the decade, just as his career should have been taking off, were relatively dry ones. As he explains in his 1980 autobiography This Life, those were the years in which he became politically aware and astute, largely because Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist crusade punished exactly the types of liberal-minded directors drawn to working with him, and he was a target himself.

“Before I had learned enough about politics to get a fix on McCarthy, I found myself victimized by the indiscriminate gusts from his demagoguery. With a long arm that was never ready to help but always ready to hurt, the Senator smeared and paralyzed much of the area I had by now chosen to spend my life in. Before I could understand any of it, I was blacklisted. I wasn’t able to work.” Poitier further explains, “I couldn’t really say for sure whether it was a blacklist or my Black face that was keeping me out of work.” Regardless, Poitier had learned to think for himself, and that alone made him a threat to the country’s conservative forces.

Fortunately, the breadth and quality of roles available to him would improve in the next decade: He kicked off the 1960s by reprising a role he’d played on Broadway in Daniel Petrie’s film version of Lorraine Hansbury’s groundbreaking play A Raisin in the Sun. He played a teacher trying to maintain order over a rough-and-tumble classroom in London’s East End in To Sir, With Love (1967), and starred opposite jazz singer Abbey Lincoln in the romantic comedy For Love of Ivy (1968); he also wrote the story from which the screenplay was drawn. In 1967, he played the “guess who” in Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, as a young man engaged to a white woman and meeting her parents—played by Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy—for the first time.

In This Life, Poitier suggests that he was merely lucky to have come along when he did, at a time when Hollywood was finally shifting its thinking on the presence of Black characters in movies. Beginning in the early 1960s, he writes, “year by year more and more white Americans were willing to pay their way into a theater to see entertainment about Blacks or involving Blacks,” which made the studios rethink their “rigid and generally insulting policy for dealing with America’s Black citizens.” Poitier is overly modest in assessing his own role in that shift: “Though history will accurately acknowledge my presence in those proceedings, my contribution was no more important than being at the right place at the right time, one in that series of perfect accidents from which fate fashions her grand designs. History will pinpoint me as merely a minor element in an ongoing major event, a small if necessary energy.”

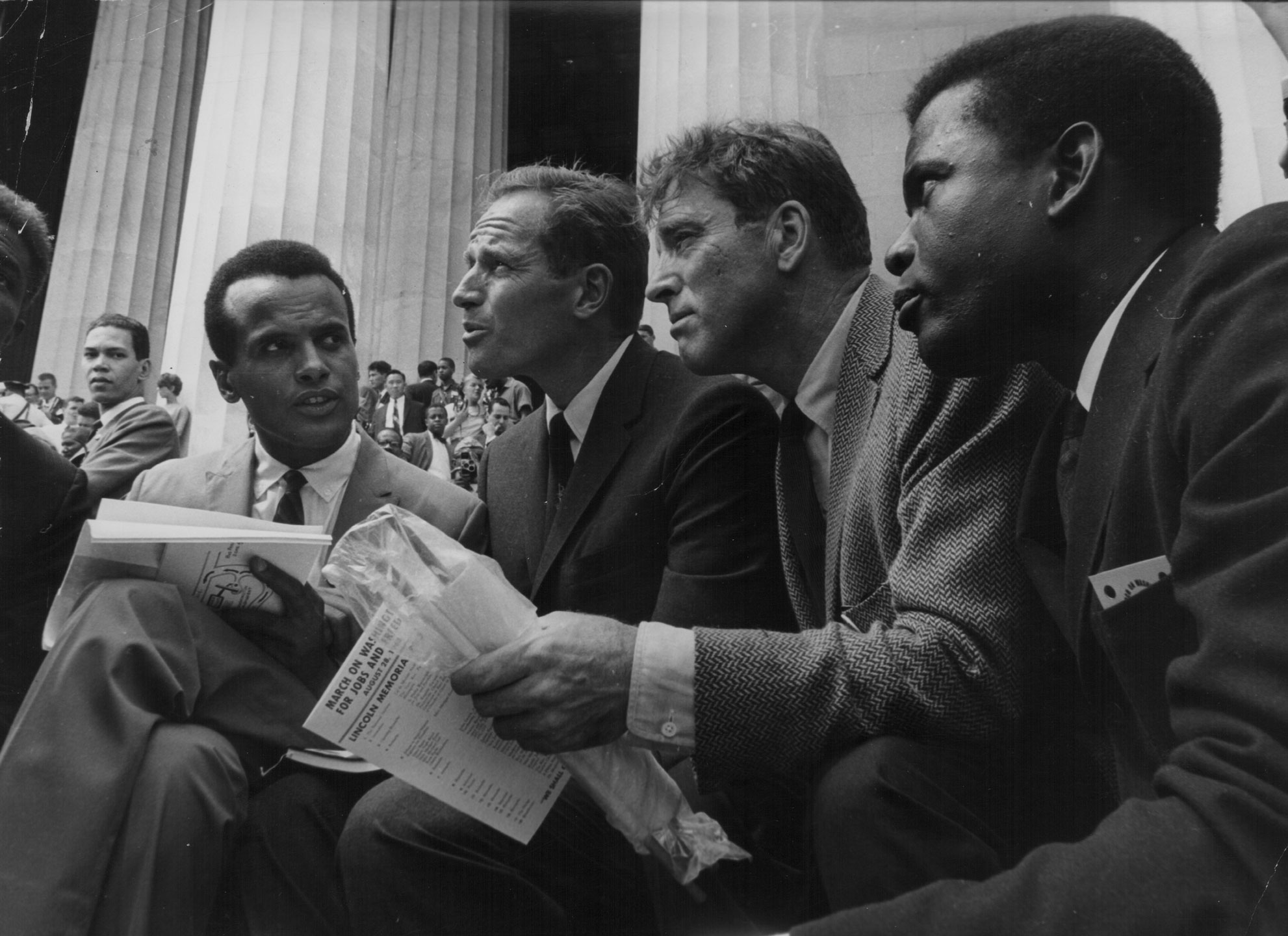

Yet nothing about Poitier’s energy has ever seemed small. As a Civil Rights activist in the 1960s, working alongside his friend and friendly rival Harry Belafonte, he once delivered an emergency infusion of cash to Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader Stokely Carmichael in Mississippi. The money was desperately needed for bail and court costs, and the mission was dangerous, even for stars like Poitier and Belafonte: The Ku Klux Klan was clearly aware of their presence, and during their overnight stay in a local family’s home, they were awakened at 4 a.m. by the sound of a mysterious car pulling up outside their window. Luckily, watchmen provided by the Committee were stationed outside, with shotguns, ready to protect them from trouble if necessary.

You could argue that everything Poitier did, every role he took, was in some way political: His very presence spoke to audiences through myriad channels. He was an actor of elegant bearing, a quality that some present-day cultural observers have used against him, citing it as a major reason white audiences so easily accepted him in the 1950s and ’60s: The idea is that he was palatable to whites because he was a nonthreatening Black presence who often played saintly roles. White folks could point to their acceptance of him as proof they weren’t racist.

His thought-provoking performances

But that view of Poitier and his work doesn’t account for all that he meant to audiences in the 1950s and 1960s, to Black audiences who weren’t used to seeing anyone like themselves onscreen, but also to white audiences who weren’t used to seeing Black performers in leading roles at all. He made the world suddenly seem bigger—even if you thought you knew everything, guess what? You didn’t. Here was a man who could surprise you, a man who, with the delivery of a single pointed line or even just a commanding glance, could shift your thinking in small ways or large ones. Actors can work only in the world, and the era, they inhabit. No performance should be evaluated—or, worse, devalued—in strictly revisionist “we know better now” terms. A good performance also has an interior meaning, an energy that charges and changes the air around it, leaping the synapse from one human being to another.

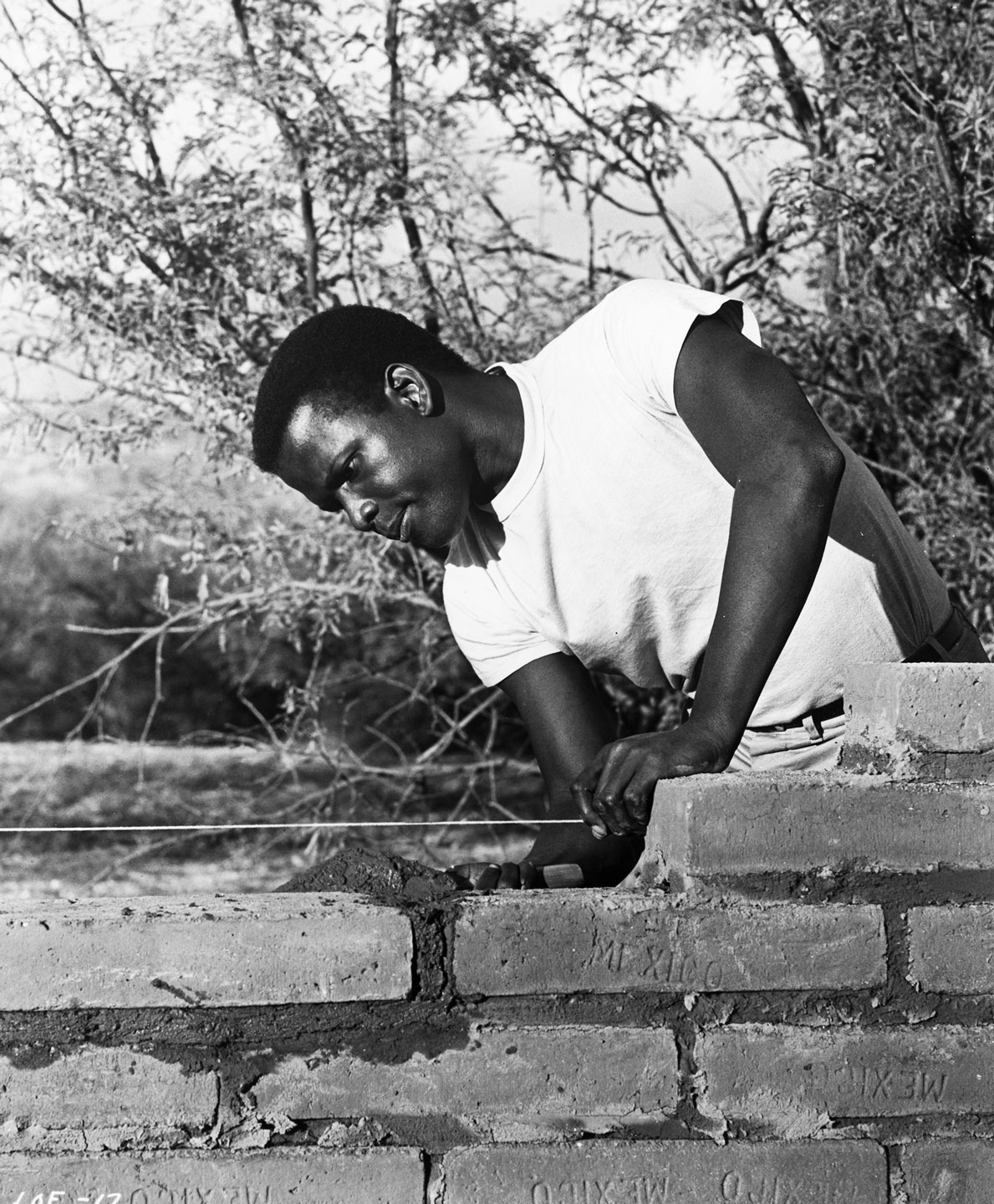

The performances that win Academy Awards aren’t always the best ones. But Poitier’s turn in Ralph Nelson’s Lilies of the Field—which earned him a Best Actor Oscar in 1964—is both purely pleasurable to watch and filled with the seemingly casual kind of power that made Poitier so extraordinary. Poitier plays Homer Smith, a free-spirited working man driving through Arizona. Stopping for some minor auto maintenance, he meets a small group of East German nuns: strange, forceful beings in straw sunbonnets who have set up a modest convent in the desert. Their no-nonsense Mother Superior (played Austrian actress Lilia Skala) believes Homer has been sent to them by God to build a chapel, and so they put him to work—though they sidestep the fact they don’t have any money to pay him.

The subtext of a Black man’s being expected to work for white people for free is hardly lost on Homer, and he tries to leave the nuns. But something keeps drawing him back, and the push-pull between him and these demanding but also vulnerable women is the film’s defining dynamic. In some ways, they’re awful: Skala’s Mother Maria has a particular block when it comes to uttering the words “thank you.” But part of what makes Poitier’s performance so remarkable is Homer’s gentle but forceful dexterity in asserting his own selfhood, even as he helps these women obtain something they desperately need. Lilies of the Field is about finding grace even if you don’t believe in God, or in someone else’s specific idea of God, and Poitier’s Homer is perfectly balanced between being the savior and the saved. This is a performance filled with generosity and humor, but it’s also muscular and definitive. Everyone can use a little saving, but one’s strengths can save others, too.

Poitier didn’t win an Oscar—and, in fact, wasn’t even nominated—for one of his finest performances, in Norman Jewison’s 1967 In the Heat of the Night. Poitier plays a Philadelphia homicide detective, Virgil Tibbs, who, while waiting for a connecting train home after visiting his mother in the South, gets picked up in a small Mississippi town for a murder he obviously didn’t commit. The sheriff in charge, Rod Steiger’s Gillespie, is deeply resentful when he’s forced to accept Tibbs’ help in solving the crime. The whole town, in fact, eyes Tibbs with something worse than suspicion: They just can’t believe that a Black man could be so well-dressed, so intelligent, possessed of such excellent manners—and that he knows exactly how to go about solving a crime that has them flummoxed.

Tibbs suffers a stream of disses and indignities, some of them overtly racist and others more grimly insidious. So much of Poitier’s performance here consists of watching and listening. His eyes register bigotry as if it were a bonfire right in front of him, but his lips remain sealed. Tibbs knows the value of discretion, especially among white folks, and especially among white folks in the South. The code is written in his heart, in his blood: To survive, you’ve got to keep your head down, be sure not to draw attention to yourself—until he can stand it no longer. Poitier brings so much quiet grit to this role: In one extraordinary scene, he addresses the murdered man’s grief-stricken widow (Lee Grant) with the greatest tenderness, even though he doesn’t dare touch her. He’s businesslike, as is necessary, but his kindness radiates like an interstellar force.

His indelible impact

Kindness: How do you act that, really? The best you can do is release it into the air and hope it has the intended effect, hope that it changes something for the better. Poitier’s whole life and career was about inciting change, in big ways and small. In the 1970s, Poitier turned to directing, a way of having more control over how people of color were portrayed onscreen. He made a revisionist Western long before Quentin Tarantino got the idea, with his 1972 Buck and the Preacher, also starring his friends Belafonte and Ruby Dee. His 1974 comedy crime caper Uptown Saturday Night—also starring Belafonte, as well as Bill Cosby, Flip Wilson and Richard Pryor—was such a hit that it spawned two sequels: Let’s Do It Again and A Piece of the Action.

But Poitier will be best remembered as an actor and as a presence, a force not just on the cultural landscape but on a broader political one, too. Poitier’s Academy Award win for Lilies of the Field was a first: As a Bahamian-American, he was the first Black actor to win the Best Actor award, and the only one until Denzel Washington won, for the 2001 Training Day. (Coincidentally, Poitier also received an honorary lifetime-achievement Oscar that same evening.) In his autobiography, Poitier wrote of how, early in his career, he worked hard to rid himself of his Bahamian accent. Thank God he couldn’t erase it completely: In all of his performances you can still hear its traces, just a slight lilt in the buttery texture of that voice, as distinctive as a fingerprint. No man is just one thing. But it bears remembering that when Poitier launched his film career, white audiences had very limited ideas about what it meant to be a Black man in America, and an immigrant, no less.

Poitier knew his career had opened a door for others; he saw his own work as a beginning. The future he was building toward, starting in the 1940s, isn’t yet here: Bigotry and racism still thrive, a blight on the values Americans are supposed to stand for. But Sidney Poitier believed in, and worked for, a world without that hatred. We have only to look at his life’s work, and we can believe too.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com