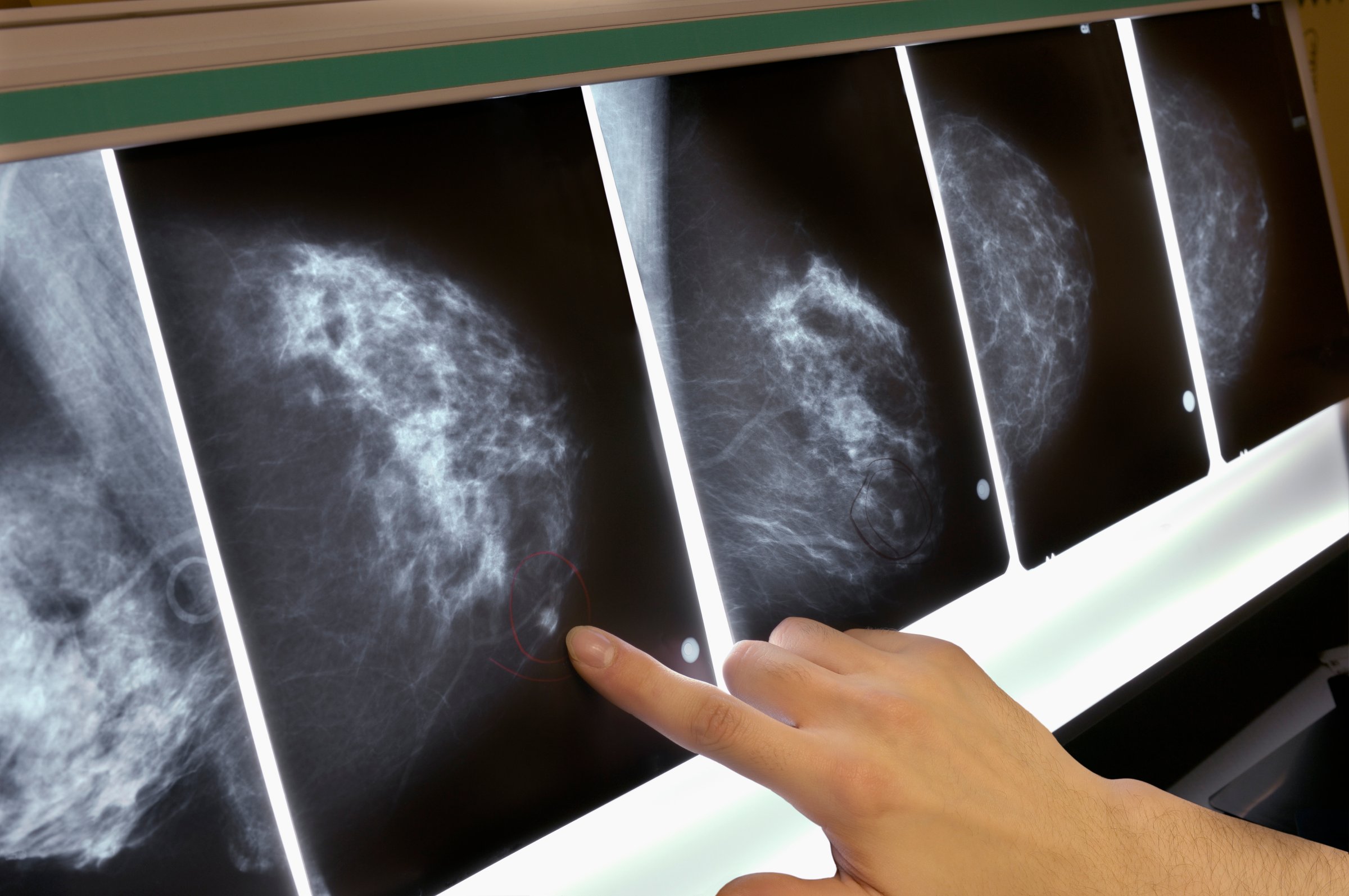

Doctors have gotten much better at detecting and treating breast cancer early. Drug and chemotherapy regimens to control tumors have gotten so effective, in fact, that in some cases, surgery is no longer necessary. In up to 30% of cases of early-stage breast cancer treated before surgery, doctors can’t find evidence of cancer cells in postoperative biopsies. The problem, however, is that there is currently no reliable way to tell which cancers have been pushed into remission and which ones have not.

That’s where an easy identifier, like a blood test, could transform the way early stage breast cancer is treated. In a paper published in Science Translational Medicine, researchers led by a team at the Translational Genomics Institute (TGen), an Arizona-based nonprofit, report encouraging results on just such a liquid biopsy. Its test, called Targeted Digital Sequencing (or TARDIS), was up to 100 times more sensitive than other similar liquid-biopsy tests in picking up DNA shed by breast cancer cells into the blood.

Currently available ways of tracking breast cancer cells in the blood are most useful in people with advanced cancer. In those conditions, cancer cells litter the blood with fragments of their DNA as they circulate throughout the body to seed new tumors in other tissues like the bone, liver and brain. But in early-stage breast cancer, these cells are, by definition, scarcer.

To address the problem, the research team, which included scientists at Arizona State University, the City of Hope, Mayo Clinic, and the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, developed a new way to pick up elusive cancer DNA. They genetically sequenced tumor biopsy tissue from 33 women with stage 1, 2, or 3 breast cancer, most of whom received drug or chemotherapy treatment prior to getting surgery to remove their tumors. By comparing the tumor sequence to the sequence from the patients’ normal cells, the scientists isolated potential mutations that distinguished the cancer cells and identified those that were most likely to be so-called “founder mutations”—genetic aberrations present in the original cancer cells and carried into the resulting tumor.

On average, each patient harbored about 66 such founder mutations. For each patient, the scientists combined the founder mutations to form a personalized assay, which could then be used to pick up signs of breast cancer DNA in blood samples. Combining a number of mutations together turned out to be a more sensitive way to detect tumor DNA than trying to pick up a single or a small number of mutations in an already small number of tumor DNA fragments present in the blood.

They combined this approach with a new strategy for amplifying the scarce tumor DNA found in a blood sample by preserving the size of these snippets and attaching unique molecular identifiers to them to make them more easily detectable.

At the start of the study, TARDIS was able to find tumor DNA in the blood samples of all the patients; other liquid biopsies for breast cancer currently in development have reported picking up 50% to 75% of the cancer cases.

After the pre-surgery treatment TARDIS detected circulating tumor DNA in the blood in concentrations as low as 0.003%, or 100-fold more sensitive than other tests being developed.

“This is an important advance,” says Dr. Debu Tripathy, professor and chair of the breast medical oncology department at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who was not involved in the study. “This test can help identify those with early stage breast cancer who may still have residual cancer in their body that may not be detectable with standard scans.”

That could help guide treatment, by, for example, determining which patients require closer monitoring for recurrent growths. Because the sequencing identifies the genetic mutations contributing to the tumor, the test could also help doctors to decide which targeted drug therapies, which are designed to address specific cancer mutations, to prescribe for their patients.

Most importantly, the test could help women whose tumors are effectively eliminated by their pre-surgery treatment to avoid an operation altogether since the blood test would reassure her and her doctor that no residual tumor DNA remained.

“If we could really know with a more accurate degree of certainty that a patient has no residual disease, the test would help reduce unnecessary treatment that she or he may have otherwise received,” says Dorraya El-Ashry, chief scientific officer of the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. ”Conversely, if the patient still had residual disease, and the test could pinpoint the next, most effective therapy, that would provide more precise patient care— moving closer toward the ultimate goal of personalized medicine.”

Muhammed Murtaza, co-director of the center for non-invasive diagnostics at TGen, says TARDIS needs to be tested in a larger group of breast cancer patients before it can be rolled out to doctors’ offices. His team is planning to study the test’s efficacy in about 200 breast cancer patients, in order to clarify exactly what levels of tumor DNA found in the blood are most likely to lead to recurrence. They are also exploring how modified versions of TARDIS could be applied to other cancers, like esophageal, colorectal, pancreatic and prostate.

There’s even encouraging precedent for this sort of a liquid biopsy. Doctors routinely rely on a blood test for chronic myeloid leukemia, for example, to track patients’ response to targeted drugs that treat specific mutations driving the cancer. “Applying this same technology to more common solid cancers like breast cancer is the new frontier,” says Tripathy.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com