With cities around the world hitting record-breaking temperatures, finding quick and effective ways to cool off has become a top priority. Air-conditioning is a great option, but not every country can afford or sustain the energy infrastructure required to climate cool their populations. Even in wealthy countries, some individuals may not be able to afford air-conditioning.

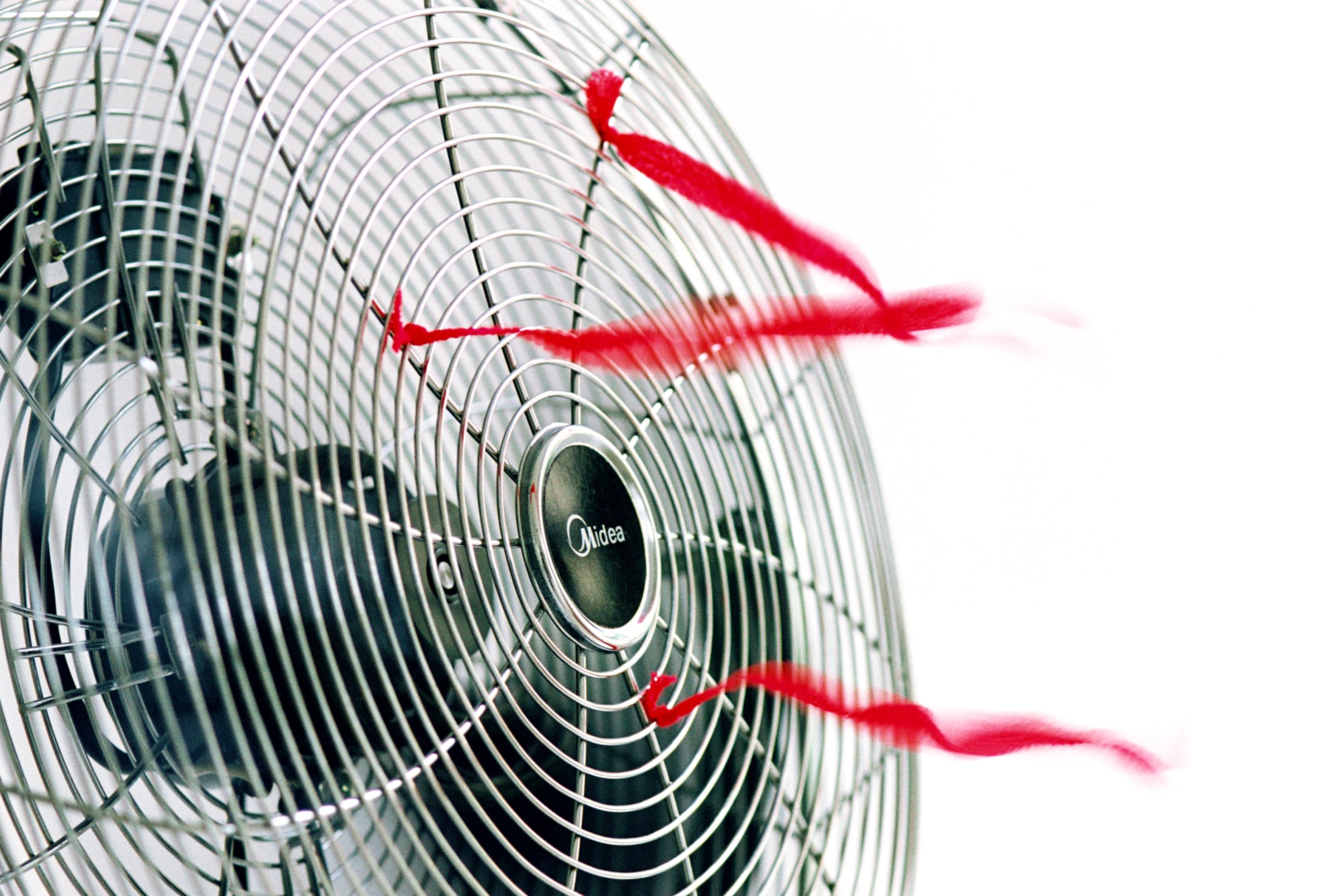

Fans are another useful way to cool off, but the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warn that when temperatures hit the high 90s° Fahrenheit, fans don’t help in protecting people from heat-related illnesses. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recommends that people not use fans when the heat index temperature—a combination of the temperature and humidity—climbs above 99°F.

Ollie Jay, associate professor of health sciences at University of Sydney and director of the thermal ergonomics lab, and his team wanted to test the validity of these public health recommendations. In a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, Jay and his colleagues documented a study involving 12 healthy men who volunteered to sit for two hours each in one of two different conditions: dry heat, with a heat index of 115°F (46°C), and humid heat, with a heat index of 133°F (56°C). The researchers took four different measures to gauge potential heat stress that the volunteers experienced: their rectal temperature, the strain on the heart (using heart rate and blood pressure), dehydration, and their reports of thermal comfort on a standardized scale.

The researchers found that under the hot and humid conditions, fans lowered the men’s core body temperature and reduced the heat-related strain on their heart, as well as improved their thermal comfort. Under the hot and dry conditions, however, the fans increased body temperature, the strain on the heart, and thermal discomfort. In other words, the fans worked better at higher heat index temperatures.

There’s a physiological explanation: When air temperature soars above skin temperature, then the exchange of air between the body and the air switches; rather than dissipating away from the body, heat from the hotter air starts to flow into the body. “It’s how a convection oven works,” says Jay, “A turkey cooks faster if the fan is on because you’re adding heat by convection faster.” So turning on a fan will only speed up the shift of hot air into the body, making you feel warmer, and potentially raising your body temperature to unhealthy levels.

“Fans at any temperature up to 104°F, where there is some kind of humidity, are beneficial,” says Jay. “But as the temperature goes higher, if it’s dry then fans are progressively less useful and potentially detrimental.”

The good news for those in the U.S. is that the majority of the country experiences humid heat, and if there is considerable humidity, fans can be helpful in cooling people off. “Humans sweat, and it is by far the most effective way of cooling the body,” says Jay. “If there is extra air flowing across the skin [from a fan] it helps sweat that would otherwise sit on the skin, to evaporate. That’s a good thing, a great thing.”

Jay notes that many people may not be taking advantage of this cooling method because public health groups advise people not to use fans above a heat index temperature of 99°F. He is now working with public health agencies to revise their advise about when people should rely on fans. His team will need to gather more data on different groups of people, including young children and the elderly, but he says is “pretty confident that for a young healthy group, there is scientific evidence showing fans do help.”

Given the toll that high energy cooling solutions like air conditioning have on the environment, finding less taxing alternatives, like fans or dousing with cool water, is critical for the world, he says. “The heat problem is not going away,” he says. “And there are lots of ways to cool the body without having to rely on air conditioning.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com