After the Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, on Aug. 6, 1945, “a city died, and 70,000 of its inhabitants.” The B-29 bomber stayed airborne, hovering above a terrifying mushroom cloud.

This “dreadful instant,” as TIME once put it, helped speed the end of World War II, launched the atomic age and began an ethical debate over the decision to use nuclear weapons that has continued for more than 70 years — and that has extended to questions about the plane itself.

The Enola Gay is a B-29 Superfortress, which pilot Paul Tibbets named after his mother, and which had been stripped of everything but the necessities, so as to be thousands of pounds lighter than an ordinary plane of that make. In 1945, it was given an important task. “It was just like any other mission: some people are reading books, some are taking naps. When the bomb left the airplane, the plane jumped because you released 10,000 lbs.,” Theodore Van Kirk, the plane’s navigator, later recalled. “Immediately [Tibbets] took the airplane to a 180° turn. We lost 2,000 ft. on the turn and ran away as fast as we could. Then it exploded. All we saw in the airplane was a bright flash. Shortly after that, the first shock wave hit us, and the plane snapped all over.”

The plane returned to Tinian Island, from which it had come. A few days later, on Aug. 9, the U.S. dropped another atomic bomb, this time on Nagasaki. While it did not drop the bomb on Nagasaki, the Enola Gay did take flight to get data on the weather in the lead-up to the second strike on Japan.

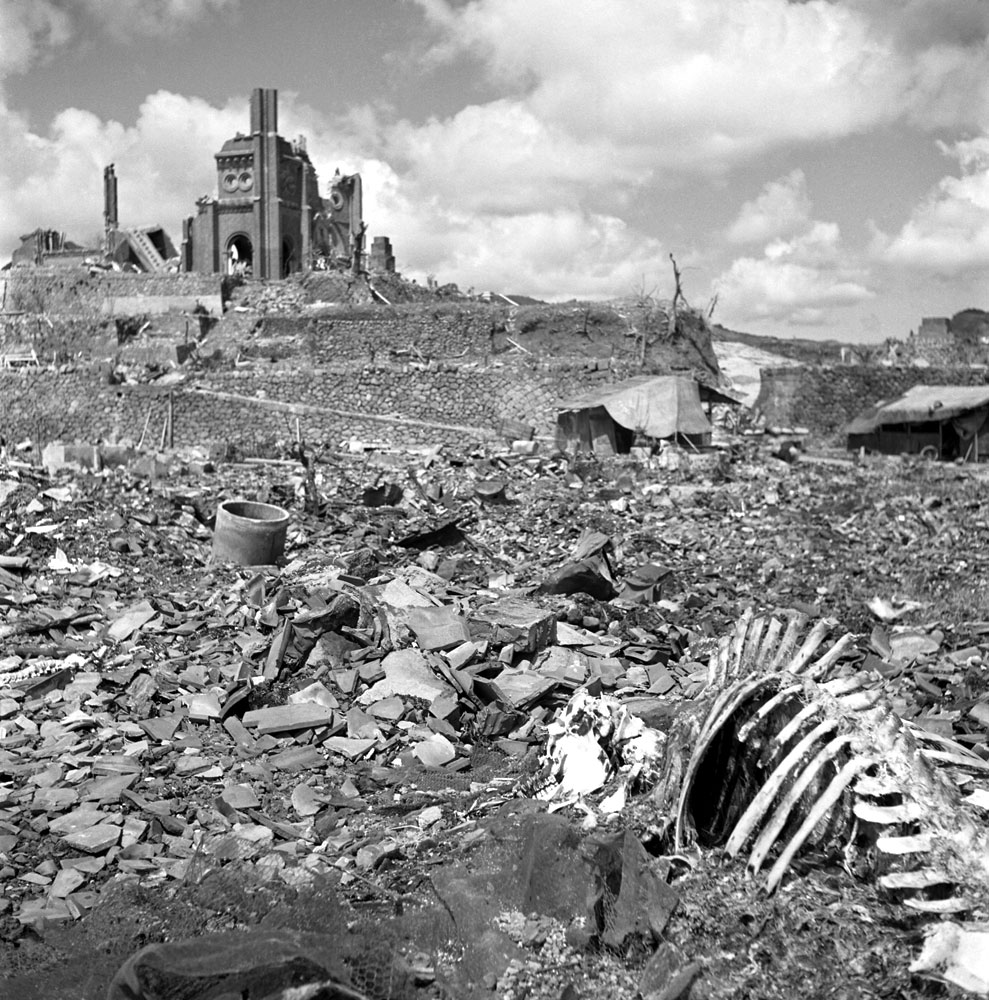

Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Photos From the Ruins

After the war, the airplane took flight a few more times. In the aftermath of World War II, the Army Air Forces flew the Enola Gay during an atomic test program in the Pacific; it was then delivered to be stored in an airfield in Arizona before being flown to Illinois and transferred to the Smithsonian in July 1949. But even under the custody of the museum, the Enola Gay remained at an air force base in Texas.

It took its last flight in 1953, arriving on Dec. 2 at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. As the Smithsonian recounts, it stayed there until August of 1960, until preservationists grew worried that the decay of the historic artifact would reach a point of no return if it stayed outside much longer. Smithsonian staffers took the plane apart into smaller pieces and moved it inside.

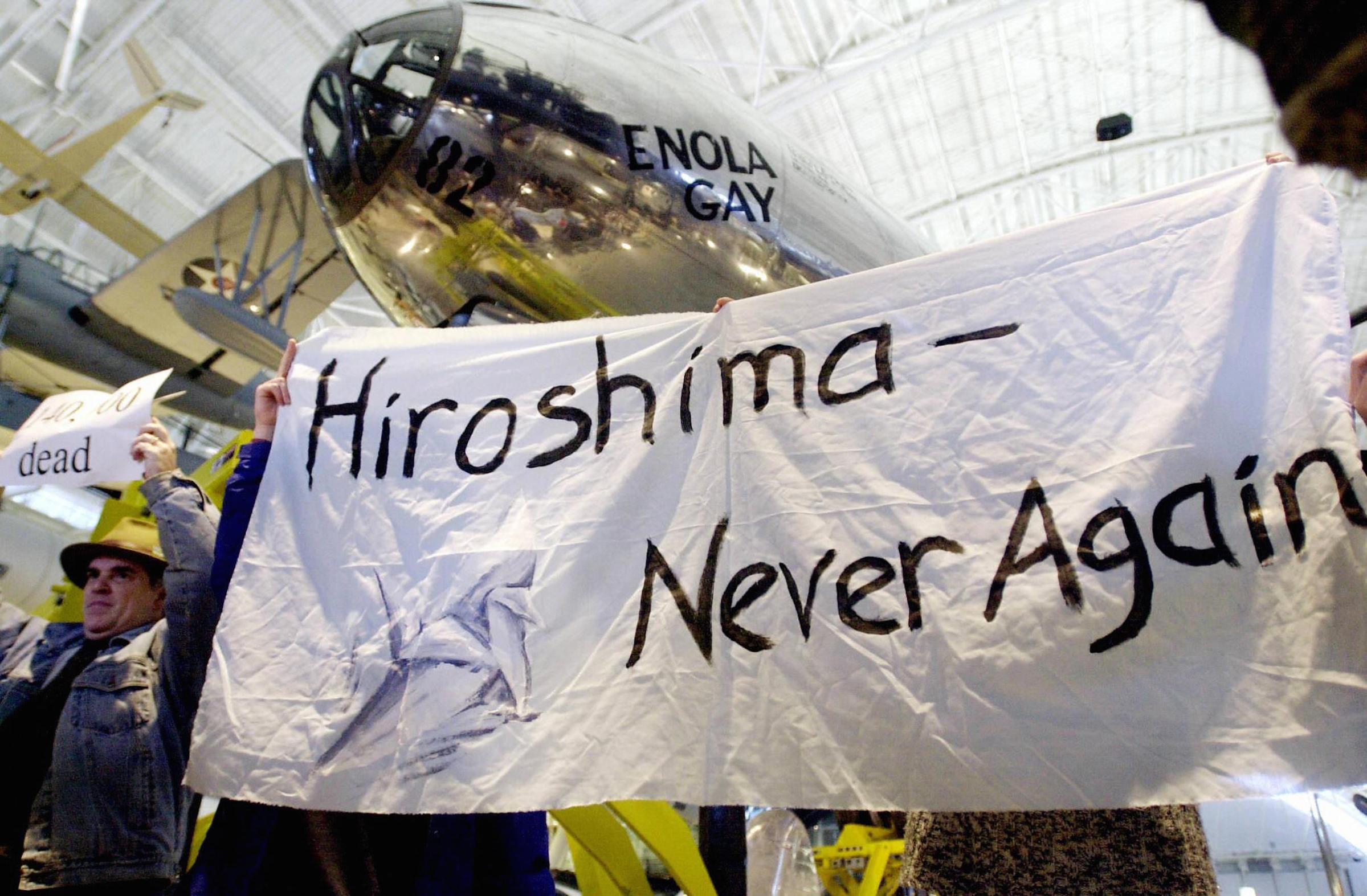

By the time the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Japan approached, the Smithsonian had already spent nearly a decade restoring the plane for exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. But when the nearly 600-page proposal for the exhibit was seen by Air Force veterans, the anniversary started a new round of controversy over the plane, as TIME explained in 1994:

The display, say the vets, is tilted against the U.S., portraying it as an unfeeling aggressor, while paying an inordinate amount of attention to Japanese suffering. Too little is made of Tokyo’s atrocities, the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor or the recalcitrance of Japan’s military leaders in the late stages of the war — the catalyst for the deployment of atomic weapons. John T. Correll, editor in chief of Air Force Magazine, noted that in the first draft there were 49 photos of Japanese casualties, against only three photos of American casualties. By his count there were four pages of text on Japanese atrocities, while there were 79 pages devoted to Japanese casualties and the civilian suffering, from not only the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki but also conventional B-29 bombing. The Committee for the Restoration and Display of the Enola Gay now has 9,000 signatures of protest. The Air Force Association claims the proposed exhibition is “a slap in the face to all Americans who fought in World War II” and “treats Japan and the U.S. as if their participation in the war were morally equivalent.”

Politicians are getting in on the action. A few weeks ago, Kansas Senator Nancy Kassebaum fired off a letter to Robert McCormick Adams, secretary of the Smithsonian. She called the proposal “a travesty” and suggested that “the famed B-29 be displayed with understanding and pride in another museum. Any one of three Kansas museums.”

Adams, who is leaving his job after 10 relatively controversy-free years, sent back a three-page answer stiffly turning down her request for the Enola Gay. The proposed script, he says, was in flux, and would be “objective,” treat U.S. airmen as “skilled, brave, loyal” and would not make a judgment on “the morality of the decision [to drop the bomb].”

Meanwhile curators Tom Crouch and Michael Neufeld, who are responsible for the content of the display, deny accusations of political correctness. Crouch claims that the critics have a “reluctance to really tell the whole story. They want to stop the story when the bomb leaves the bomb bay.” Crouch and Neufeld’s proposed display includes a “Ground Zero” section, described as the emotional center of the gallery. Among the sights: charred bodies in the rubble, the ruins of a Shinto shrine, a heat-fused rosary, items belonging to dead schoolchildren. The curators have proposed a PARENTAL DISCRETION sign for the show.

The veterans, for their part, say they are well aware of the grim nature of the subject. They are not asking for a whitewash. “Nobody is looking for glorification,” says Correll. “Just be fair. Tell both sides.”

Eventually, the criticism from veterans, Congress and others resulted in major changes to the exhibition. “[The show] will no longer include a long section on the postwar nuclear race that veterans groups and members of Congress had criticized. The critics said that the discussion did not belong in the exhibit and was part of a politically loaded message that the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan began a dark chapter in human history,” the New York Times reported. That version of the exhibition opened in 1995, displaying more than half of the plane, the restoration of which was still unfinished.

But the exhibition proved popular. When it closed in 1998, about four million people had visited it, according to a report by Air Force Magazine‘s Correll — the most ever to visit an Air and Space Museum special exhibition to that point.

It would take until 2003 for the full plane to be displayed, at the Air and Space Museum’s location in Chantilly, Va. That opening again provoked protest, but it can still be seen there.

And as long as it is on display, the questions it raises are likely to continue — after all, they have been with the Enola Gay since it first became a household name.

Even on board, the men who flew the plane knew as much. Van Kirk, the navigator, later described the crew as having had the immediate thought that, “This war is over.” And copilot Robert A. Lewis kept a personal log of the mission, which — when it was later made public — offered a look at what else they were thinking. “I honestly have the feeling of groping for words to explain this,” he wrote of the moments after the mushroom cloud rose, “or I might say My God what have we done.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com